Why Dyslexia Isn’t Broken Reading but Brilliant Rewiring

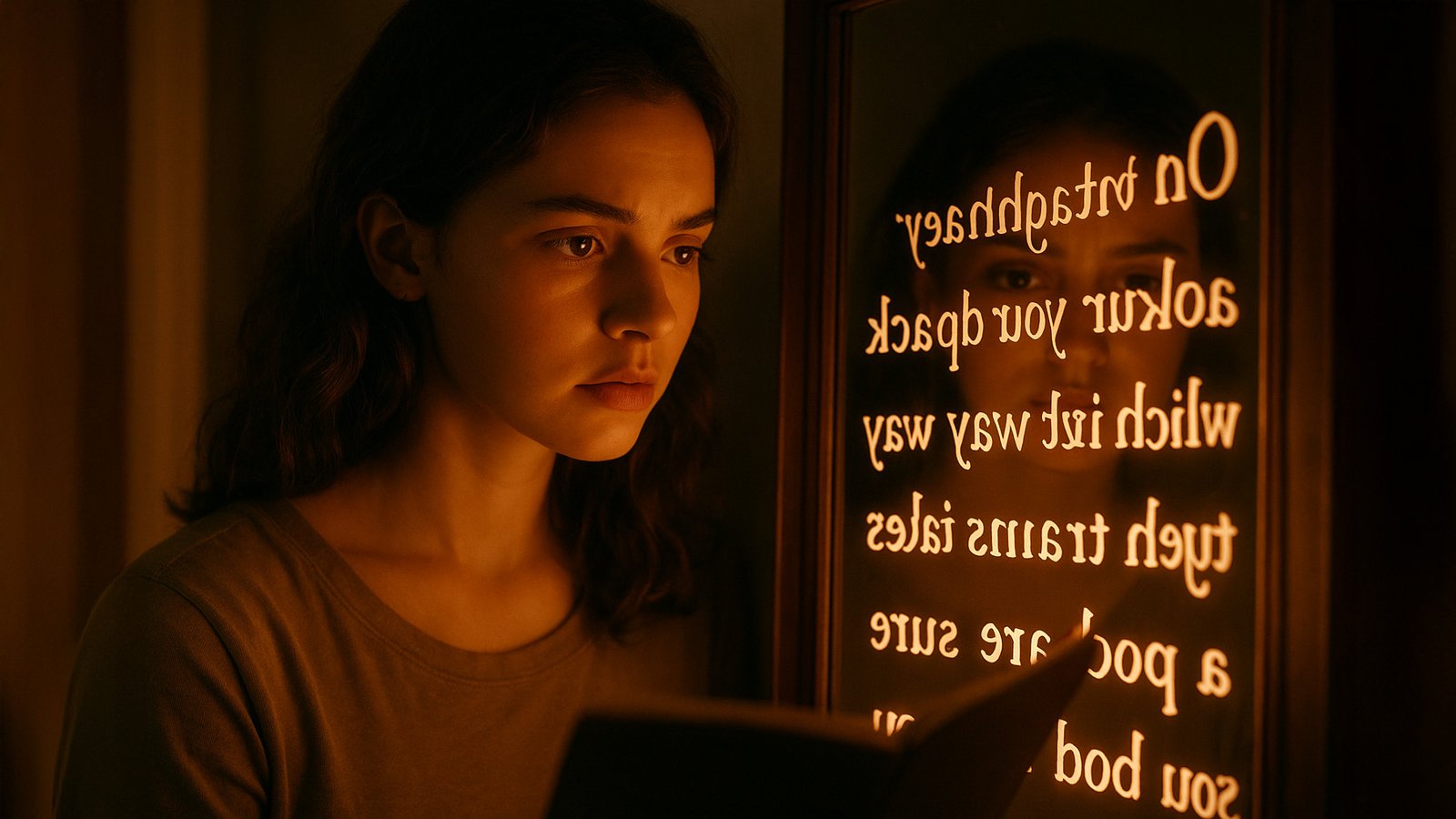

Imagine trying to read a book where every sentence feels like it’s been tossed into a blender. Letters swap places, words slip off the page, and your brain insists that ‘was’ and ‘saw’ are just twins playing tricks on you. That’s what reading can feel like for someone with dyslexia, though the truth is a bit less dramatic and a lot more fascinating.

Dyslexia has been around far longer than its name, which only entered the medical vocabulary in the late 19th century. But long before anyone put a label on it, there were kids in classrooms quietly wondering why their brains refused to play along with the alphabet game. Today we know a lot more, but the story of dyslexia is still tangled between myths, breakthroughs, and the occasional politician promising that AI will fix it all.

The modern definition of dyslexia is shifting. Forget the outdated idea that it’s about letters dancing on a page. The experts have spoken — quite literally, in something called the Delphi Study, where nearly sixty of them debated, voted, and eventually agreed that dyslexia is better seen as a cluster of processing difficulties that mess with reading and spelling. Not a disease, not a defect, but a difference in how the brain deals with written language. It’s a continuum, meaning that some people find reading mildly annoying while others face an uphill battle every time they open a menu.

That’s the beauty and the headache of dyslexia: it refuses to fit neatly into boxes. One person might struggle with spelling but breeze through comprehension, another might read at a snail’s pace yet have the imagination of a novelist. It’s not an on-or-off switch, more like a dimmer dial that changes depending on the lighting — or in this case, the teaching.

In Britain, around ten percent of the population sits somewhere on that dyslexic spectrum. That’s millions of people navigating a world designed for quick readers and fast typists. Four percent have what experts call severe dyslexia, though many would rather call it ‘severe irritation with bureaucracy’ after trying to get a proper diagnosis. Getting assessed can feel like applying for a mortgage with extra paperwork. The process depends on where you live, who you ask, and whether your local authority happens to fund assessments that year. Some children get help in primary school; others wait until university, when someone finally realises their essays aren’t bad — just written by a brain wired differently.

For all the awareness campaigns, the system still feels patchy. Teachers know dyslexia exists, but training varies wildly. Some schools have brilliant support plans; others think a pastel-coloured overlay will do the trick. Research from Durham University found that almost half of professionals assessing dyslexia still believe myths that should have been retired decades ago. Like the idea that dyslexic people see letters ‘jumping’ on a page or that certain font colours magically unlock literacy. Spoiler: they don’t.

Yet despite the confusion, progress keeps coming. Neuroscientists are poking around the brain’s reading circuit to see how it learns to recognise words, and they’ve spotted that dyslexic brains connect the dots a little differently. The University of California’s Dyslexia Centre is even working on ways to detect risk early, before a child falls behind. Think of it as predictive text for human learning. Meanwhile, in Edinburgh, researchers have confirmed that dyslexia shares a genetic overlap with ADHD. The same cluster of 174 genes and 49 genetic regions might influence both. Nature clearly loves to multitask.

Genetics explains some things, but not everything. Environment plays a huge role — particularly how reading is taught. Imagine two kids with the same genes: one gets clear, phonics-based teaching that shows how letters link to sounds; the other is told to memorise whole words. The first may learn to read fluently, the second may quietly fall behind. That’s why experts keep banging on about early detection. Catch it early, teach explicitly, and you can close much of the gap.

There’s no single cure because it’s not a disease. Dyslexia is a different operating system, and teaching needs compatible software. The right kind of support can make a massive difference. University College London found that targeted interventions boosted reading outcomes by five months compared to standard teaching. That might not sound revolutionary until you’re a parent watching your child finally read aloud without panic.

Of course, in 2025 we can’t talk about education without dragging AI into it. The UK’s Science and Technology Secretary recently announced that artificial intelligence could ‘level up opportunities for dyslexic children’. It sounds lovely, though one suspects the robots might need levelling up first. Still, adaptive learning platforms are genuinely promising — they can track patterns, adjust pace, and offer instant feedback in ways that humans can’t always manage one-on-one. For a student who’s spent years being told they’re slow, a patient AI tutor that never sighs could be a small miracle.

Outside classrooms, the conversation about dyslexia is evolving fast. Adults are stepping forward to talk about how it shapes their working lives. Once, dyslexia was a quiet embarrassment; now it’s part of the broader movement celebrating neurodiversity. Employers are waking up to the fact that people who think differently often see opportunities others miss. Richard Branson famously credits dyslexia for making him focus on the big picture. Steven Spielberg turned storytelling into an art form partly because words were never his easiest medium. The world runs on ideas, not spelling tests.

Still, adult dyslexics face their own battles. Job applications, emails, endless forms that assume everyone writes fluently — it’s enough to make anyone fantasise about living off-grid. Adult literacy programmes exist but often rely on outdated methods or expect people to announce their dyslexia to HR before help arrives. There’s a growing push for more subtle support, like text-to-speech software built into workplace systems or dyslexia-friendly fonts that make documents easier to read without shouting ‘special needs’ in bold letters.

The publishing world is catching up too. Dyslexia-friendly books are no longer just for children. Publishers like Books on the Hill are reprinting classics with larger spacing, cream paper, and sans-serif fonts that ease visual stress. They’re proving that accessibility and sophistication can coexist. You can read Jane Austen in a dyslexia-friendly format without feeling like it’s a simplified edition for reluctant readers.

Beyond literature, technology keeps expanding the toolkit. Speech-to-text apps, audiobooks, digital pens, even smart glasses that can read aloud — the options multiply each year. What used to be seen as a disadvantage can now become a design challenge. The world is slowly learning to adapt to brains that process differently rather than trying to fix them.

For all the optimism, there’s still a gap between research and reality. The British Dyslexia Association’s latest report titled Mind the Gap points out how inconsistent support remains. Schools and workplaces often talk about inclusion, but implementation is patchy. One student might get extra time in exams, another just gets sympathetic looks. The irony is that early and consistent support costs less in the long run than years of academic frustration and low confidence.

Meanwhile, researchers are asking what the dyslexia community actually needs. In a recent paper, participants ranked practical, real-world support far above more brain scans or academic theory. They want inclusive classroom design, training for teachers, and understanding for adults. The scientists, bless them, are slowly listening.

One of the most refreshing shifts is how dyslexia is framed now. It’s no longer seen purely as a literacy problem but as part of a diverse range of cognitive profiles. Dyslexic brains often excel at visual thinking, creativity, and holistic reasoning. They can struggle with short-term memory or sequential processing, but they see patterns others miss. It’s why architects, designers, and entrepreneurs often share this trait. The modern workplace, built on collaboration and innovation, might just be the perfect habitat.

Of course, not every dyslexic person wants to be a visionary. Many just want a fair shot at education, work, and dignity. The new definition from the Delphi Study helps because it removes the idea of ‘normal’ versus ‘defective’. Everyone processes language differently, and dyslexia sits on a continuum of human variation. There’s something quietly revolutionary about that.

What’s next? Expect more technology, more advocacy, and hopefully fewer myths. AI and adaptive learning tools will continue to change education. Researchers are already testing VR experiences that help teachers understand what it feels like to have dyslexia — a clever way to replace pity with empathy. Global research is widening too: recent projects are creating assistive software for adults with dyslexia in languages like Sinhala, showing that it’s not just an English-speaking issue.

There’s still work to do. Dyslexia remains under-identified in many parts of the world. Girls and women are often overlooked because they tend to mask symptoms more effectively. People from working-class or immigrant backgrounds face extra hurdles accessing assessments. The fight for equitable access continues, but awareness is spreading faster than ever.

If you strip away the academic jargon, dyslexia is about storytelling. Every person with it carries a narrative of frustration, adaptation, and often brilliance. The child who memorises books because decoding them is too hard. The teenager who hides their difficulties behind jokes. The adult who avoids emails but excels at strategy meetings. Their stories reveal that reading and writing, though vital, are just one way of expressing intelligence.

Perhaps the real irony lies here: society designed its gatekeeping system around literacy, yet some of the world’s greatest minds have struggled with it. The same system that penalises slow readers celebrates their creativity once they break through. Dyslexia doesn’t erase intelligence; it challenges the rules about how intelligence should look.

So maybe it’s time we stop treating dyslexia as a problem to solve and start seeing it as a pattern to understand. The letters might look confusing on paper, but the minds behind them are often remarkably clear. They just read the world differently — and maybe, just maybe, that’s what the world needs more of.