Homer: The Ancient Greek Poet Who May Never Have Existed

If you ever find yourself lost somewhere between myth and history, you’ll probably bump into Homer. Not Homer Simpson, though the confusion is understandable. This Homer lived around the 8th century BCE, give or take a few centuries, and managed to become the most famous poet no one can quite prove existed. His name floats through ancient Greek culture like a rumour that never went away, attached to two epics that have defined Western storytelling for nearly three millennia: The Iliad and The Odyssey. The man might be a legend, but his words are the bedrock of every tale about war, love, pride, and adventure ever since.

Imagine a world without books, without Netflix, without even pub Wi‑Fi. That’s where Homer’s audience lived. Stories weren’t read, they were performed. Picture a singer of tales, a blind bard perhaps, reciting verses to the rhythm of a lyre in smoky halls, while warriors and farmers listened wide‑eyed. The idea of authorship back then was slippery; poetry was a collective memory, a long chain of retellings, each performer adding their own twist. Yet somehow, the poems attributed to Homer feel like the work of a single mind: structured, dramatic, rhythmically alive. They pulse with the kind of coherence you don’t get from a committee.

Scholars have obsessed over him ever since. Was Homer one man, or a tradition of singers whose work was stitched together? Did he really live in Ionia, that sun‑soaked coastal region of modern‑day Turkey where Greek culture met the East? Or was he from Chios, or Smyrna, or a dozen other cities that later claimed him like a celebrity hometown brag? The evidence is mostly poetic—literally. Linguists point out that the dialect of the Iliad and Odyssey is a strange hybrid, a mashup of Ionian and Aeolic Greek, suggesting centuries of oral evolution before the words were ever written down.

What’s certain is that whoever Homer was, he wrote—or recited—stories that outlasted empires. The Iliad is not just about a war; it’s about rage. The kind of rage that makes gods nervous and men tragic. It opens with one of the most famous lines in all literature: “Sing, goddess, of the wrath of Achilles.” Achilles, the ultimate warrior, sulks, fights, kills, and mourns in a way that makes him feel disturbingly modern. The poem’s real genius lies in how it takes a slice of the Trojan War, just a few weeks out of ten years, and turns it into an emotional battlefield where honour and pride do most of the killing.

Then comes The Odyssey, a sequel so different it could have been written by another person entirely. If The Iliad is about the fury of men, The Odyssey is about the cunning of one. Odysseus, the wanderer, takes ten years to get home, meeting gods, monsters, witches, and occasionally his own bad decisions. His journey is less about geography and more about survival and identity—what it means to be human when you’re constantly tested by the whims of fate. Between one epic about war and another about homecoming, Homer managed to define both the hero and the anti‑hero before the concepts even existed.

Archaeology, of course, has tried to catch up. When Heinrich Schliemann dug up what he claimed was Troy in the 1870s, people rushed to call it proof that Homer had been right all along. Never mind that Schliemann’s methods were more bulldozer than brushstroke. He still gave the world a story it wanted to believe: that myth and history might overlap in the ruins of Hisarlik. Later digs revealed more complexity—layers upon layers of cities, built and burned, reminding us that truth in Homer’s world is always plural.

What’s fascinating about Homer isn’t just his influence, but how adaptable his work remains. Ancient Greeks memorised and performed him. Medieval monks copied him. Renaissance scholars worshipped him. Modern filmmakers reinvent him endlessly—Brad Pitt growling as Achilles in Troy (2004) or Coen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? turning Odysseus into a Depression‑era conman. Even James Joyce’s Ulysses is basically Homer on Guinness and anxiety. The man—or myth—has been repackaged more times than a pop album.

One of the strangest things about Homer’s poems is how alive they feel. His characters don’t behave like distant myths; they’re impulsive, sarcastic, jealous, tender. Achilles throws tantrums worthy of a footballer. Odysseus lies like it’s a sport. Helen doubts herself, Andromache pleads, Priam mourns. The gods are petty, meddling, magnificent, and often ridiculous. You can sense Homer’s smirk behind it all, a wry understanding that divine drama and human folly are basically the same thing—just with more thunderbolts.

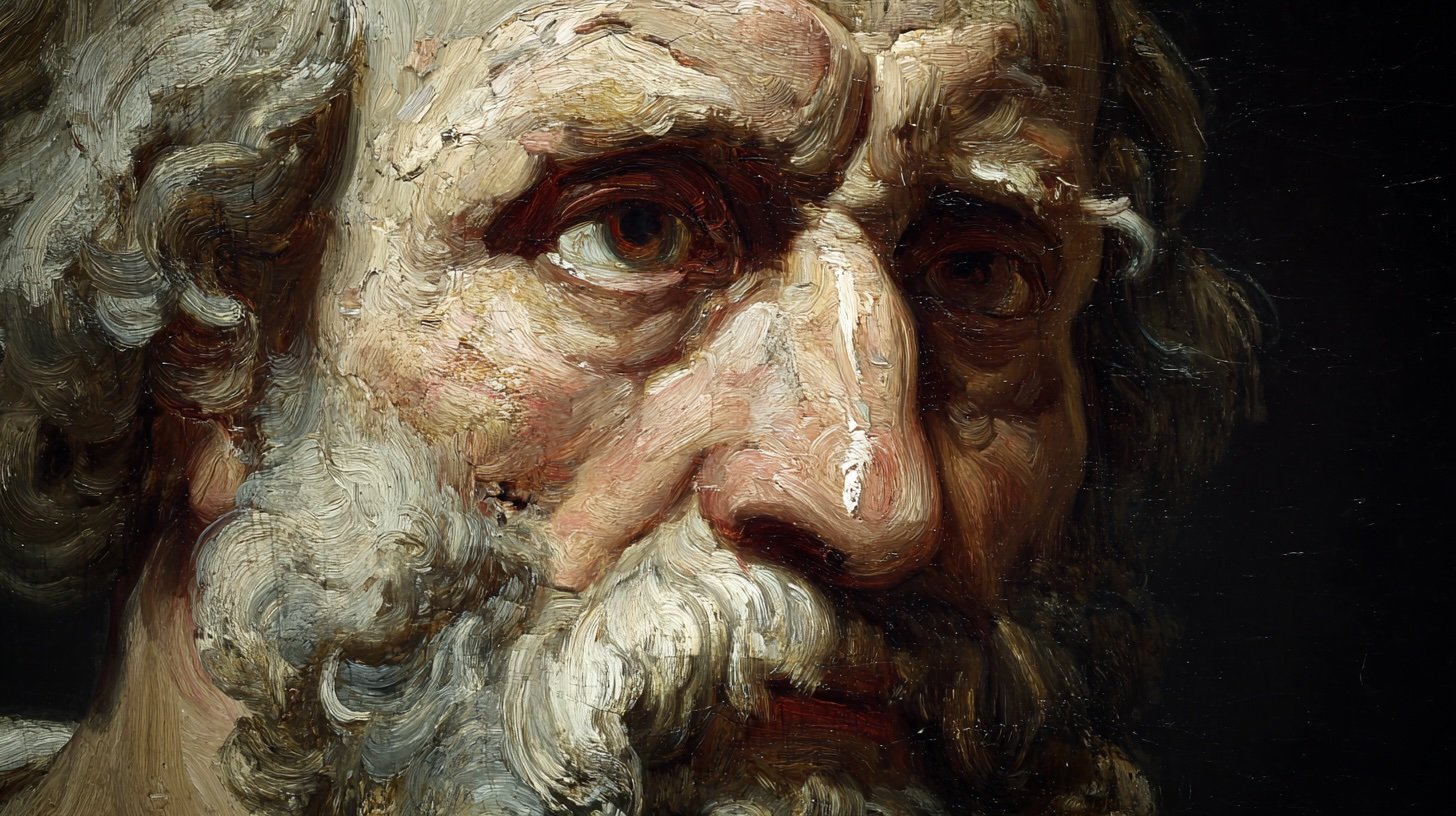

For centuries, people have argued about whether Homer was blind. The ancient Greeks themselves said so, possibly because poets were thought to see inwardly rather than outwardly. But maybe blindness was a metaphor for insight: he didn’t need eyes to see the truth of human nature. Or perhaps it’s all just a poetic flourish that stuck. After all, when you’re mythic enough, details like eyesight become optional.

Then there’s the question of how these enormous works survived before writing was common. Imagine remembering over 15,000 lines of verse and performing them flawlessly. The oral tradition relied on formulaic phrases—those repeated epithets like “swift‑footed Achilles” or “rosy‑fingered dawn”—which acted as memory hooks for the singer. Far from lazy repetition, these lines were the poetry’s scaffolding, allowing it to flex and breathe during live performance. Homer didn’t just tell stories; he built an entire storytelling technology.

It’s worth remembering that when people say Homer invented Western literature, they’re not exaggerating. The Greeks considered him their first teacher. Plato both adored and distrusted him; Aristotle analysed him; Alexander the Great carried a copy of The Iliad as if it were a battle manual. Every epic since—from Virgil’s Aeneid to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings—owes something to that original blueprint of gods, wars, and homesick heroes. Even the phrase “epic” itself became shorthand for anything larger than life because of him.

Yet for all his fame, Homer remains a ghost. There’s no portrait, no grave, no autograph. Just the verses, floating from one century to the next, too vivid to die. In a sense, that’s the most poetic outcome imaginable. The poet who sang of immortality achieved it not through flesh, but through rhythm and memory. He became the echo of his own themes: loss, endurance, and the longing for home.

Today, you can read Homer in a dozen translations, from the stately Victorian to the sharp and modern. Emily Wilson’s recent English version of The Odyssey shook up the old male‑centric tradition with its brisk pace and clarity. She made Odysseus sound less like a marble statue and more like a man trying to talk his way out of trouble—which, to be fair, he usually was. That’s the beauty of Homer: every era finds itself in him. The ancient Greeks saw divine order, the Victorians saw moral struggle, we see psychological realism. He contains them all.

And the language—mythic yet conversational—has a strange immortality too. Take that image of the dawn stretching her rosy fingers across the sky. It’s so simple, yet it turns morning into a goddess’s gesture. Homer’s metaphors aren’t lofty decorations; they’re alive, physical, full of movement. You can almost feel the sea wind in his verbs, the tension of the bowstring, the exhaustion of battle. If poetry is meant to make the world visible, Homer made it cinematic.

But maybe what keeps us coming back isn’t just his grandeur. It’s the irony that for all the gods and heroes, Homer’s world feels so recognisably human. His soldiers argue over credit, his kings sulk, his queens scheme, his wanderers just want to get home. Strip away the armour and you could drop them straight into any century. Achilles might be a celebrity athlete refusing to play after an insult. Odysseus could be a man navigating airports instead of islands. The settings change, the storms don’t.

Even the endings refuse neat closure. Achilles wins eternal fame but dies young. Odysseus reaches Ithaca only to find home isn’t quite what he remembered. There’s always a catch, a melancholy twist. Homer seems to know that victory and loss are twins, that time humbles even the strongest. Maybe that’s why we still read him—not to learn how to conquer, but how to endure.

So yes, Homer was an ancient Greek poet, if by poet you mean someone who understood the absurd theatre of being alive. He turned oral tradition into art, myth into psychology, and war into metaphor. He taught the world that stories could be both entertainment and mirror. And somewhere between the walls of Troy and the waves of the Aegean, he left us with the most human of lessons: that the journey never really ends, it just becomes another song waiting to be sung.