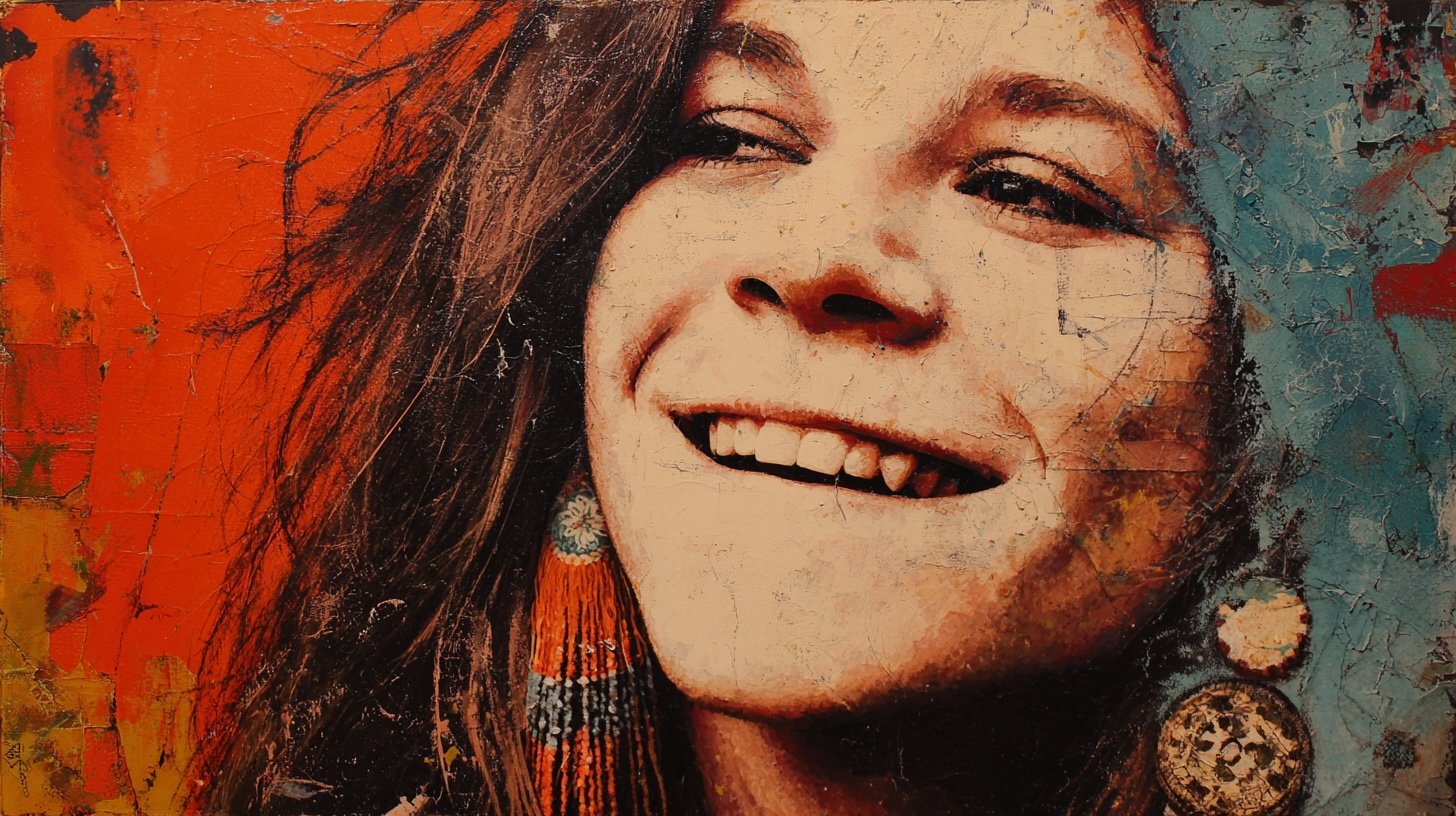

Why Janis Joplin ’s Rock Feels So Uncomfortable

Janis Joplin never sounded safe. Even when the band played gently and the lyrics hinted at freedom or release, her voice carried risk. It cracked, stretched, rasped, and sometimes seemed to tear itself apart in real time. Because of that instability, listening still feels faintly uncomfortable. The discomfort does not come from age or fashion. Instead, it comes from a refusal to settle.

Her singing never reassures. It does not smooth edges or offer easy resolution. Rather, it demands attention and punishes half-listening. The voice arrives exposed, without padding or apology. As a result, it keeps the listener alert in a way few recordings do.

She grew up in Port Arthur, Texas, a refinery town shaped by conformity and suspicion of difference. In such places, fitting in functions as a social requirement rather than a suggestion. Joplin failed that test early. She dressed differently, listened obsessively to old blues records, and irritated people simply by being herself without apology. Classmates later remembered her as loud, awkward, and defiant. Consequently, that reputation settled in long before any professional ambition took shape.

Music entered her life first as refuge rather than career plan. Blues singers like Bessie Smith and Lead Belly offered a vocabulary for pain that felt more truthful than anything around her. Those voices did not hide struggle behind polish. Instead, they leaned into it. Joplin absorbed that lesson quickly and never unlearned it. She understood that sounding perfect mattered far less than sounding true.

By the early 1960s, she drifted through Texas and California folk scenes, singing where she could and surviving where she had to. Eventually, San Francisco offered both freedom and danger. The city rewarded intensity and treated restraint with suspicion. For someone like Joplin, this atmosphere felt like permission. She could be loud, emotional, and unfiltered without immediate punishment. At the same time, however, that environment amplified every weakness she already carried.

Her real breakthrough came with Big Brother and the Holding Company. The band never aimed for finesse. It played loudly, roughly, and sometimes sloppily. Paradoxically, that worked in her favour. Nothing competed with her voice. When they took the stage at Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, the audience did not need persuasion. Joplin did not glide into the spotlight. Instead, she attacked it, turning performance into exposure.

Critics struggled to describe what they had witnessed. Rock music had not yet decided how women were supposed to sound when they refused to behave. As a result, language lagged behind experience. What felt undeniable on stage resisted tidy explanation in print.

Success followed quickly, though never comfortably. Cheap Thrills turned her into a star, yet it also fixed her inside an image she did not fully control. The wild singer. The uncontrolled woman. The embodiment of excess. These labels travelled faster than the music itself. Interviews lingered on drinking, relationships, and appearance. She noticed this imbalance and resented it. Still, she sometimes played into the role, because expectation can function as armour.

As her career progressed, she became more deliberate than the mythology suggests. She listened closely to phrasing and obsessed over timing. Moreover, she argued with producers and bandmates about arrangements because she knew what she wanted a song to do emotionally. That side of her rarely appears in simplified retellings. It clashes with the myth of reckless genius. Yet the recordings reveal control beneath abrasion. She knew precisely when to push and when to pull back.

Her solo work expanded that range further. Songs often sounded explosive, yet they followed a clear internal logic. The drama built carefully, and the breaks landed exactly where they needed to land. Later recordings revealed restraint few people expected. She sang softly when the material demanded it, allowing songs to breathe rather than overpowering them. That choice signalled growth rather than collapse.

Fame, however, never resolved the deeper conflict. Joplin wanted connection without compromise and recognition without containment. Those desires rarely coexist peacefully. Romantic relationships disappointed her. Friendships blurred under pressure. Meanwhile, drugs offered temporary quiet, and alcohol filled the gaps between shows and cities.

The late 1960s rock scene did not reward moderation. Excess operated as proof of authenticity, while suffering became currency. Artists were expected to burn brightly and briefly. Joplin understood that narrative even as it consumed her. She joked about it and leaned into it publicly. Quietly and inconsistently, though, she also tried to escape it.

Pearl, released after her death, complicates the familiar story. The album sounds focused and surprisingly playful. It suggests someone beginning to trust her voice rather than wrestle with it. Humour appears alongside force, and control replaces constant struggle. Because of that, the ending feels harder to accept, not easier.

Her death in 1970 froze her image at twenty-seven. The number became symbolic and almost ritualised. It offered a tidy frame for a life that resisted neatness. Addiction mattered. Loneliness mattered. Exhaustion mattered too. Reducing everything to a cautionary tale misses the point. She did not chase destruction as an aesthetic. Instead, she chased relief.

Gender shaped how her story circulated. Male performers who self-destructed often earned romantic narratives of tortured genius. Joplin received warnings instead. Critics called her crude, excessive, and unladylike. Praise arrived laced with surprise, as if power sounded unnatural coming from a woman. She recognised this imbalance and pushed back when she could, although resistance rarely paid.

Her influence now feels both everywhere and nowhere. Many singers cite her, yet few attempt imitation. That restraint makes sense. Her voice resists copying because it emerged from a specific mix of temperament, experience, and refusal. What artists borrow instead is permission. Permission to sound imperfect. Permission to prioritise feeling over finish.

Listening today, her recordings do not function as background. They interrupt. They demand presence. In a culture obsessed with control, her lack of restraint feels radical rather than nostalgic.

What remains most striking is how immediate she still sounds. The voice arrives without buffer or distance. It refuses to behave, even now. That refusal, more than any mythology, explains why Janis Joplin continues to matter.