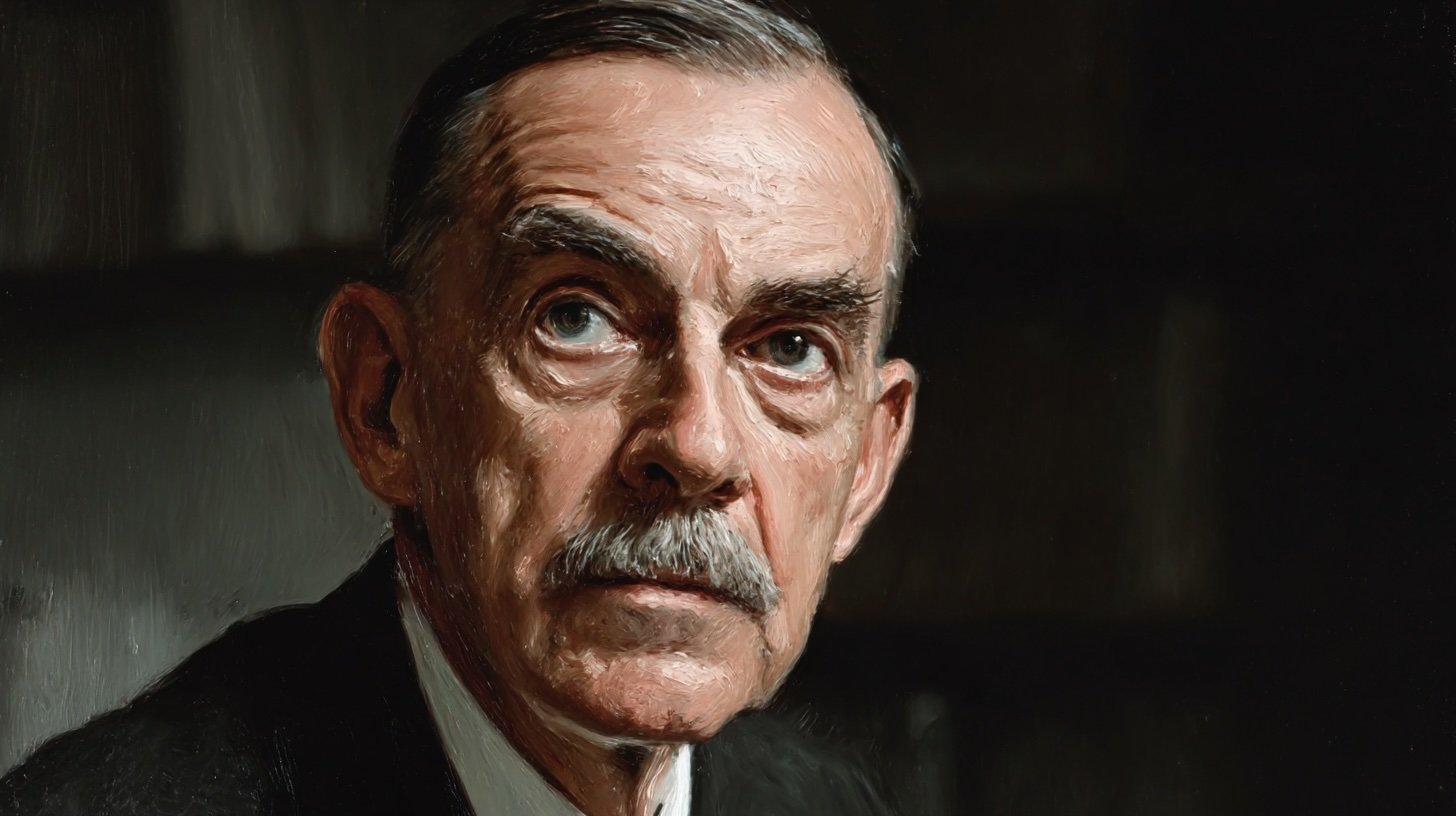

Thomas Mann: Europe’s Favourite Pessimist with a Nobel Prize

Thomas Mann never set out to become the literary conscience of Germany, but fate, a Nobel Prize, and a stubborn moustache seemed to conspire against him. Born in 1875 in the quaintly respectable city of Lübeck, Mann was the sort of child who probably organised his toy soldiers according to Kantian principles. His father was a wealthy grain merchant and senator, which sounds very glamorous until you remember that being a senator in 19th-century Lübeck meant presiding over fish tariffs and municipal drainage. Still, young Thomas was groomed for bourgeois greatness—an ambition he disappointingly subverted by becoming a writer.

Mann’s early years were a curious mix of naval dreams and literary flirtations. For a while, he fancied becoming a sea captain, but seasickness and Nietzsche intervened. The turning point came when he moved to Munich, which at the time was a hotbed of artistic ferment, cabaret existentialism, and facial hair experimentation. There, surrounded by anarchists, poets, and people who took breakfast at noon, Mann found his spiritual home. It was all very decadent and delightful, the perfect breeding ground for his first big novel, Buddenbrooks, published when he was just 26.

Buddenbrooks was a polite slap in the face to everything his family held dear. A sweeping generational saga about the slow decline of a merchant dynasty (sound familiar?), it was a deeply German, intensely psychological, and thoroughly literary affair. His relatives probably smiled tightly at dinner. Critics, on the other hand, threw garlands. The book earned Mann the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, though the committee very diplomatically cited only Buddenbrooks and neatly avoided his more complicated works.

Now, Mann wasn’t your average tortured genius. He enjoyed a good cigar, wore three-piece suits even at the beach, and treated irony like it was fine porcelain—precise, cold, and not for everyday use. Mann was deeply conservative in temperament but somehow became the poster child for Weimar modernism. He wrote slowly, brooded thoroughly, and deployed semicolons like surgical instruments. Mann was a master of the long game: paragraphs that spanned pages, characters that wrestled with metaphysics, and stories that unravelled like philosophical debates in formalwear.

Then came Death in Venice, a novella so stuffed with aesthetic tension it practically needed a chaperone. On the surface, it’s about a respectable writer who goes to Venice for a holiday and ends up obsessing over a beautiful Polish boy. Below the surface? Decay, mortality, art, repression, and a great deal of hair cream. Mann turned a sunlit beach into a theatre of existential doom, which is honestly quite a feat. The story cemented his reputation as a High Priest of Serious Literature and also raised more than a few eyebrows.

Because yes, Thomas Mann had layers. Beneath the patrician poise and intellectual gravitas was a man who kept a diary that was, shall we say, surprisingly candid. These Tagebücher were not published until long after his death, but when they did surface, they revealed a man profoundly conflicted about his sexuality. Married with six children, Mann nonetheless spent a significant portion of his interior monologue thinking about beautiful young men. Scholars, delighted and discomfited, have since reinterpreted entire shelves of his work through this lens. Death in Venice, in particular, now reads like less of a subtle metaphor and more of a full-throated whisper.

As the world moved toward war in the 1930s, Mann made what was, for him, a dramatically un-German decision: he took a stand. Not a lukewarm essay or a carefully nuanced footnote, but an actual, public, moral stance. He denounced Hitler. He fled Germany. And he ended up in Switzerland, then the United States, which he regarded with a mixture of admiration and quiet horror. (Imagine a man in spats watching someone eat a cheeseburger with their hands.)

Mann’s American years were oddly prolific. He delivered lectures, radio broadcasts, and essays that helped shape the Allied cultural war effort. He became the literary voice of exile, the expatriate sage warning about the abyss. But he also never quite fit in. Hollywood tried to wine and dine him, but Mann, ever the North German senator’s son, found palm trees a bit gauche. He lived in Pacific Palisades, near other exiled luminaries like Arnold Schoenberg and Lion Feuchtwanger, but remained defiantly European in posture and pessimism.

One of the crown jewels of his exile period was Doctor Faustus, a novel that is either a work of genius or a 500-page dare. It tells the story of a composer who sells his soul for artistic greatness—yes, it’s Goethe meets Schoenberg with a cameo from Nietzsche’s ghost. It’s dense, brilliant, claustrophobic, and contains more fugues than an organ recital. Mann wrote it with the help of real-life composer Theodor Adorno, who probably wished halfway through that he’d stuck with sociology.

Back in Europe after the war, Mann was welcomed as a prophet, but with a slight undercurrent of national embarrassment. Germany, having tried its very best to implode, now needed voices like his to help stitch together a cultural identity that wasn’t entirely wrapped in shame. Mann obliged, but with the cool detachment of someone who had been warning about this exact thing since 1933. He spent his later years between Switzerland and frequent visits to Germany, where he was lauded, honoured, and occasionally misunderstood.

Family life in the Mann household was its own opera. His brother Heinrich Mann was also a respected novelist, albeit of a more radical and flamboyant stripe. The two had a cordial rivalry, trading literary barbs and ideological jabs over the dinner table. Mann’s children, meanwhile, were a fascinating, talented, and generally tormented bunch. Erika Mann was a war correspondent, actress, and open critic of the Nazis. Klaus Mann was a novelist and early chronicler of the exile experience, but he struggled with depression and drug addiction. The Mann children inherited both their father’s brilliance and his existential angst, which made for exceptional Christmas arguments.

Thomas Mann died in 1955, with a legacy so vast it needs a dedicated archivist and possibly a therapist. His writing influenced generations of thinkers, from Susan Sontag to Harold Bloom, and he remains a pillar of European modernism. His work is frequently assigned in university syllabi, often to the dismay of undergraduates who mistake The Magic Mountain for a brisk read. (Spoiler: it isn’t. It’s a novel about time, illness, and ennui, written at glacial pace and featuring extended conversations about x-rays.)

But there is something perversely admirable about Mann’s dedication to seriousness. In an age of literary speed dating and hot takes, he wrote novels that demanded commitment, focus, and the occasional nap. He believed literature was not just entertainment but moral instruction, psychological excavation, and aesthetic warfare. He did not write to amuse. And he wrote to diagnose.

He also remains one of the rare writers who managed to be both deeply German and yet cosmopolitan, grounded in bourgeois values yet profoundly critical of them, steeped in tradition yet quietly radical. His moustache alone carried more gravitas than most political manifestos. He was maddening, majestic, and entirely unbothered by your opinion of his semi-colons.

If there’s a lesson in Mann’s life, it’s that you can be principled without being loud, that exile sharpens the mind, and that the best literary feuds happen within families. Also, never underestimate the power of a good wool suit and a well-written sentence to change the course of culture. Or at least to make it stop and think for a moment.

In an age where literature is often consumed like takeaway, Thomas Mann remains the six-course meal you have to dress up for. You might not finish it in one sitting. You might not understand every course. But you will come away feeling like you’ve eaten something important. And possibly in need of a lie down.