The Quiet Magic of the Bouquinistes of Paris

Writers love to pretend they discovered the bouquinistes before anyone else, as if the green boxes magically sprang open the moment they strolled down the Seine with a notebook and an existential crisis. They didn’t, of course. Those boxes have been clinging to the river’s stone parapets longer than most Parisian flats have had indoor plumbing. Walking the Left Bank between Quai de la Tournelle and Quai Voltaire feels like drifting through an open‑air library curated by someone with impeccable taste, a fondness for oddities and absolutely no fear of dust.

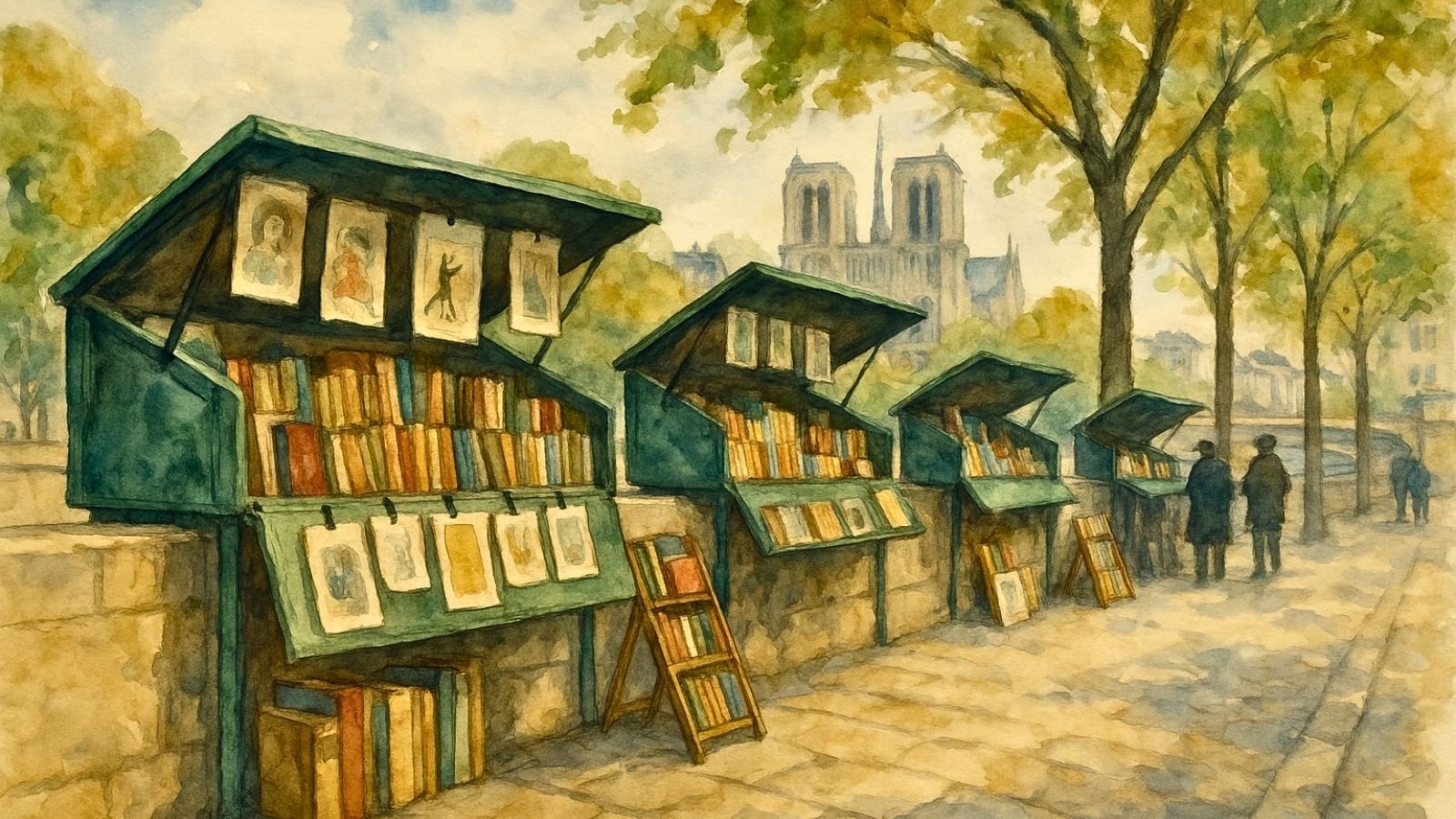

The scene always starts the same way. Notre‑Dame looms in the background, scaffolding or not, keeping a stern eye on the whole operation. The water moves with that indifferent Parisian confidence, sliding past as if it has appointments elsewhere. Then the boxes appear, lined up like a regiment of green treasure chests, quietly daring you to open them. Most people hover for a moment, trying to decide whether they’re here for a quick photograph or a proper rummage. The boxes can tell. They judge silently.

What sits inside depends entirely on the mood of the bookseller. Some pack their stalls with dog‑eared paperbacks from the seventies, their spines sun‑bleached into anonymity. Others specialise in antiquarian beauties: leather‑bound volumes with marbled endpapers that smell like old lecture halls and forgotten libraries. You might find a first edition hiding behind a postcard rack or a complete set of Balzac wedged between a stack of travel guides and a box of sepia photographs. The uncertainty is half the pleasure. Paris likes to tease.

The bouquinistes didn’t wake up one morning and decide to become cultural icons. Their ancestors in the 16th century wandered the river with crates of pamphlets and prayer books, dodging suspicious authorities and grumpy established booksellers. By the time the Pont Neuf turned into the city’s busiest social stage, these itinerant traders had already carved out a niche. They sold anything that fit in a handcart, from political tracts to cheap romances, all while avoiding the kind of censorship that tended to shorten careers.

It took a few centuries and several municipal decrees before the city finally accepted that these book peddlers weren’t going anywhere. In 1859 they received permission to stay put rather than wander like literary nomads. A few decades later, they could even leave their boxes on the parapet overnight. Paris was embracing the idea that its river wasn’t just a scenic waterway but a continuous bookstall stretching across history.

Walk the Left Bank stretch and you can almost sense the ghosts of past readers hovering behind you. Students from the Sorbonne still drift by with tote bags full of borrowed books, occasionally buying a battered volume of philosophy so they can pretend it was their idea. The literary cafés nearby have absorbed more arguments about Proust than any university department could handle. There’s something in the air here, a mix of ink, river breeze and intellectual ambition. Even the pigeons seem unusually well read.

The booksellers keep a careful balance between old‑school charm and modern practicality. They know the regulations by heart. The boxes must be the approved green, the same shade that photographs beautifully in any season. They can’t be taller than a certain height when opened, can’t sprawl too far onto the walkway and can’t turn themselves into souvenir emporiums, though some quietly test the limits with Eiffel Tower magnets peeking from behind stacks of prints. The city tolerates a certain amount of rebellion. It always has.

The UNESCO designation comes up often in conversation. People love the idea that these boxes are part of a world heritage site, as if the river chose its companions carefully. The Left Bank boxes feel particularly rooted in the city’s soul. This is the side associated with scholars, poets, oddball geniuses and those who never quite finished their dissertations. Standing there, flipping through a 1920s map of Paris or a collection of old theatre programmes, you get the sense that the river has seen everything and keeps the boxes close as a way to remember.

Some visitors arrive with a mission. They’re hunting for a specific edition, a certain illustration style, a book they once owned and foolishly lent to someone who never returned it. Others prefer serendipity. They want to be surprised by a slim novel they’ve never heard of, or a postcard showing Paris in a misty winter when the city seems to operate in black and white. The postcards alone are their own kind of time travel. Old cafés with outdoor ashtrays, cars shaped like tin toys, bridges before their railings were updated. And always the river in its eternal moodiness.

The bouquinistes themselves have weathered more storms than most small businesses. Digital books cut into the reading habits of younger generations. Tourists ebb and flow with global crises. The city occasionally threatens to rearrange the stalls in the name of progress. Even the pandemic left its mark, with long months of empty quays and boxes that stayed shut like closed eyelids. Yet the booksellers persist. Many describe their trade as a calling rather than a job. Standing outdoors in February requires a certain commitment to literature.

On a good day you might overhear a debate about Baudelaire, a negotiation over the price of an engraving, or a discussion about whether Paris looked better before the bouquinistes allowed postcard stands. On a rainy day you might find sellers huddled under umbrellas, still open for business even though the only customers are determined bibliophiles and confused joggers. The river doesn’t pause for weather and neither do the boxes.

The charm of the Left Bank stretch lies partly in what surrounds it. You can start near the Quai de la Tournelle with views of Île Saint‑Louis, wander past the graceful outline of the cathedral, cross paths with buskers whose musical skills vary wildly, and drift towards the Institut de France where the academy guards the French language like a precious jewel. The quays offer enough diversions that you can justify stopping at every single stall without feeling rushed.

Occasionally you stumble upon something unexpected: a handwritten letter from the 1930s, a political cartoon from the Dreyfus era, a bookplate bearing the name of a forgotten aristocrat, or a set of photographs showing Paris recovering after the war. Each item tells a story that might be true or only half true. It doesn’t matter. Paris thrives on ambiguity.

Collectors love the bouquinistes because they treat treasure as casually as someone selling apples at a market. A rare print might sit next to a stack of mass‑market novels priced at one euro each. A comic book from the sixties lies under a pile of travel guides discarded by optimistic tourists. The sellers have seen every reaction possible, from nonchalant browsing to desperate excitement. They know exactly how often they say the phrase, “That one is quite special.”

The future of this riverside world feels delicate. Fewer young booksellers take up the licences, partly because the work demands long days outside and partly because the economics aren’t especially forgiving. Yet there’s a growing appreciation for analogue pleasures, for tangible paper in a digital age. Visitors crave experiences that feel grounded in place, and nothing embodies Paris quite like buying an old book with the river murmuring behind you.

Evenings bring a different atmosphere. The boxes close, the lids shut like eyelids drifting to sleep, and the green containers turn into quiet silhouettes against the stone. People stroll past with ice creams or bottles of wine, and the city lights reflect on the water. The booksellers may have gone home, but their presence lingers. The riverbank never loses the faint aroma of paper and ink.

The Left Bank bouquinistes remain one of those places where time misbehaves. Hours slip by unnoticed. You tell yourself you’ll only browse one or two stalls, and suddenly the sun has moved, your bag is heavier, and you’re carrying a print of a street you’ve never walked down. The river continues its journey, unfussed, and the boxes keep offering stories to anyone willing to stop.

There’s something comforting in knowing that this tradition survives not because it’s perfectly efficient or modern but because it gives people joy. It offers a moment of calm, curiosity and gentle chaos in a city that occasionally forgets to slow down. The bouquinistes don’t need reinvention. They simply need visitors who understand the thrill of lifting a box lid and wondering what waits inside.

Walk that stretch between Quai de la Tournelle and Quai Voltaire, and you end up carrying not just whatever you purchased but a piece of Paris itself. The river has arranged the stalls like pages in a book. All you have to do is keep turning them.