The Inventor of the Guillotine Regretted Everything

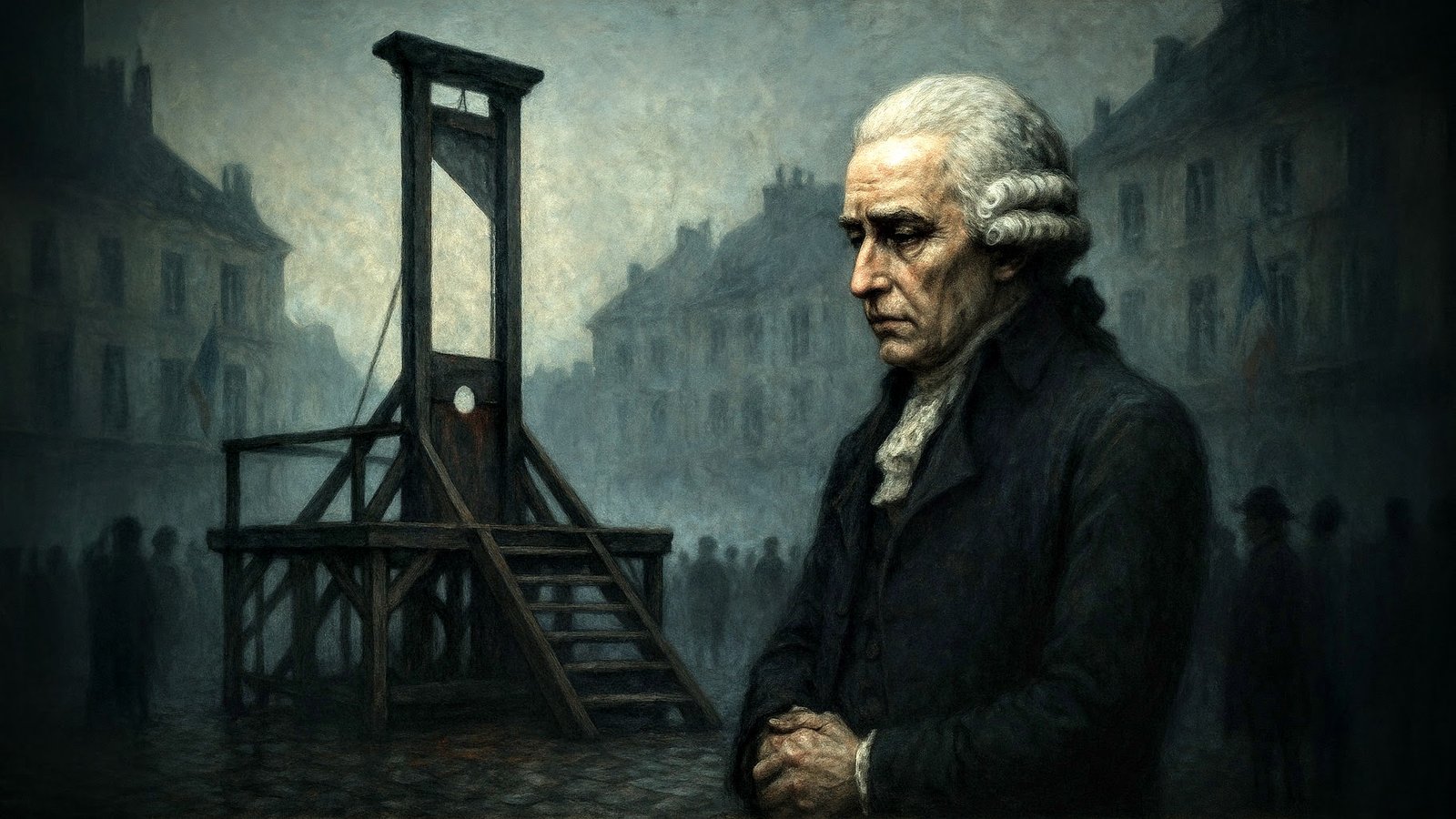

Joseph-Ignace Guillotin really thought he was doing everyone a favour. Picture it: a French doctor, wig slightly askew, passionately proposing a machine that would, in theory, make death more humane. Less chopping, more… slicing, swiftly and with egalitarian precision. It was the Enlightenment, after all. The Age of Reason. Surely we could improve on the bumbling axe jobs of medieval executioners who needed several whacks and a stiff drink to get through a morning. However, the inventor of the guillotine regretted everything.

So in 1789, when the good doctor proposed his shiny new method to the National Assembly, he believed he was ushering in an era of merciful justice. The blade would fall the same for prince or peasant. Quick, clinical, no mess, no spectacle. A democratic decapitation device, if you will. He even had a catchy slogan: “The mechanism falls like lightning, the head flies, the blood spurts, the man is no more.”

Catchy in a slightly horrifying way, but you can’t fault the man for clarity.

Now, here’s the twist that history, with its cruel sense of humour, loves to toss in: Dr Guillotin didn’t invent the guillotine. He was more of a hype man than a hardware developer. The actual building of the thing fell to Dr Antoine Louis and a German harpsichord maker named Tobias Schmidt. Yes, a man who crafted musical instruments helped design the most infamous execution machine in European history. Because life is weird like that.

So why is it called the guillotine? Because branding. Dr Louis proposed the design, but Guillotin’s name stuck. Probably because it just sounded better than “the Louis-slicer” or “Schmidt’s head-dropper.” The newspapers ran with it, the mob adored it, and by the time heads were rolling daily in Paris, the name had already been etched into the public’s imagination.

Then came the Reign of Terror.

If you’d asked Joseph-Ignace in 1793 whether he felt good about his bright idea, he probably would’ve stared at you with hollow eyes and a nervous tic. The guillotine didn’t remain the tidy, humane instrument he’d envisioned. It turned into a bloodthirsty factory, churning through the upper crust, the lower classes, clergy, nobility, revolutionaries, and eventually, their own creators.

Robespierre, Danton, Desmoulins—all cheered it on before it came for them. It became a national pastime, a street theatre of vengeance. Vendors sold programmes, kids clambered for a better view, and people dipped their handkerchiefs in noble blood like twisted souvenirs. The egalitarian dream of painless execution had morphed into a grotesque circus.

And poor Guillotin? He was horrified.

His name had become synonymous with mechanised death, despite the fact he neither built nor beheaded anyone with the contraption. He spent the rest of his life trying to distance himself from the device. Rumour had it he met his own end beneath its blade, but that’s just the icing on the irony cake. In reality, he died quietly of natural causes in 1814, though that didn’t stop the myth from circulating like a bad tabloid headline.

In fact, his family got so fed up with the association that they petitioned the French government to rename the device. The government, in a dazzling display of indifference, declined. The name stayed. His legacy, irrevocably tangled with revolutionary gore, refused to let go.

You might think this story ends with a kind of tragic nobility, a moral lesson in the perils of unintended consequences. But no, it also ends with a head in a basket, because France kept using the guillotine. For a long time.

The last public execution by guillotine happened in 1939. That’s not a typo. People still turned out in droves to watch someone lose their head before the Second World War began. And the final guillotine execution on French soil took place in 1977. While disco blared in nightclubs and Star Wars was prepping for its debut, France was still beheading people behind prison walls. If Joseph-Ignace Guillotin had been resurrected at that point, he might’ve just walked back to his grave with a sigh.

The guillotine was finally abolished in 1981, when France outlawed capital punishment altogether. But by then, the damage to Guillotin’s reputation had been done. He had tried to be a reformer. A humanist. A man of reason. Instead, he became an unwilling mascot for one of the grimmest chapters in human history.

Still, he remains an oddly sympathetic figure. Like a well-meaning inventor who designed a better mousetrap, only to watch it grow legs and start chasing people down the street. He dreamed of a world where executions didn’t need to be torture porn, where dignity could be extended even to the condemned. Unfortunately, history rarely accommodates idealists without giving them a good kicking.

So next time you hear his name, don’t just picture the blade. Picture the man beneath the powdered wig, passionately arguing for compassion, and then slowly realising he’d created a monster. He regretted everything. And yes, it ended how you’d expect: not with a bang, but with a headless whisper.