The Great Molasses Flood – When Boston Was Buried in Syrup

On a crisp January afternoon in 1919, the North End of Boston became the site of one of the stickiest disasters in American history. Yes, you read that right. The Great Molasses Flood didn’t just sound absurd—it was absurd. But it was also deadly, tragic, and weirdly instructive about hubris, corporate negligence, and the physics of syrup.

Picture it: a massive steel tank, 50 feet tall and 90 feet wide, loomed over Commercial Street, filled to the brim with over 2.3 million gallons of molasses. That’s about 8.7 million litres if you’re keeping score in metric. It belonged to the United States Industrial Alcohol Company (because of course it did), which imported molasses from the Caribbean to make alcohol. You know, for war munitions. And possibly rum. But mostly explosives.

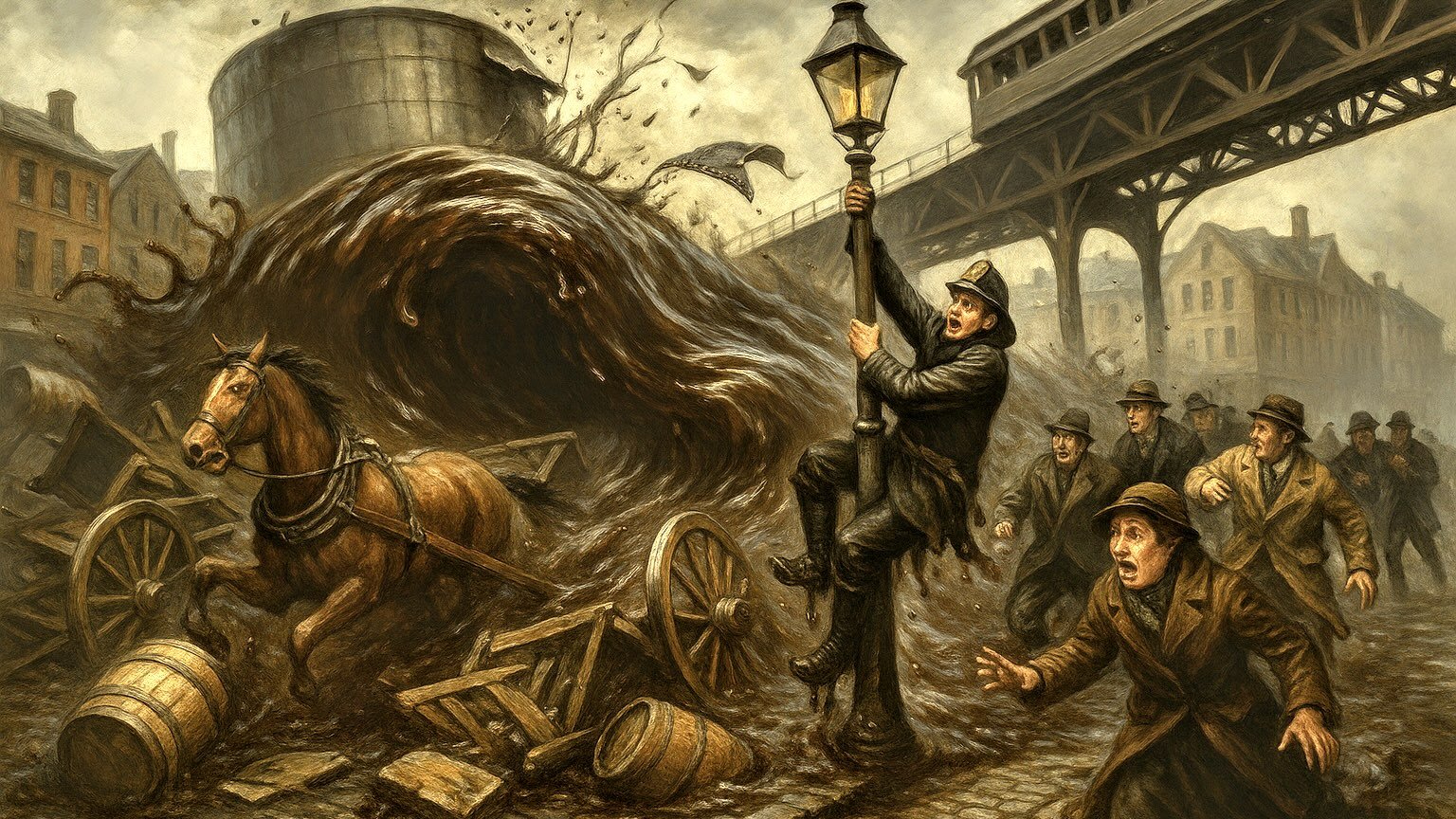

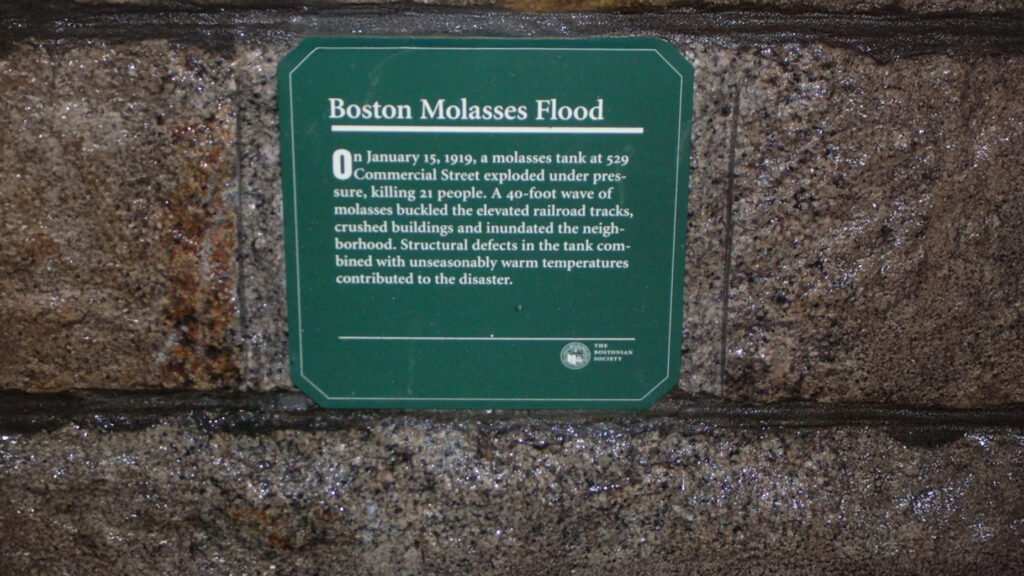

So on 15 January 1919, as the city went about its business, a sound thundered through the North End—like a machine gun, some said. Then the tank burst. Not leaked. Not cracked. Burst. With a pop and a roar, a tsunami of molasses surged through the streets at an estimated 35 mph. That’s faster than most people sprint, and it’s definitely faster than molasses is supposed to move.

This sweet tidal wave reached a height of 25 feet and flattened buildings, snapped support beams of the elevated train track, and sucked people, horses, wagons, and even freight cars into its caramel grip. Firemen at a nearby station were literally trapped inside their collapsing building as it was crushed under the wave.

Twenty-one people died. Another 150 were injured. Rescue efforts were nightmarish: thick molasses sucked rescuers down like quicksand. The cleanup took months. The smell lingered for decades. Locals swore on their Nonna’s grave that you could smell molasses on a hot day well into the 1960s.

Here’s where The Great Molasses Flood gets sticky. The tank? It had been leaking. Residents even reported children collecting the ooze in jars for fun. The company had painted it brown to hide the leaks. Not fixed them. Painted them. This may be the most on-brand act of corporate laziness in the history of American industry.

Now, the science of The Great Molasses Flood is its own dark comedy. Molasses is roughly 1.5 times as dense as water. When it’s warm, it flows fairly easily. But it was winter in Boston, and as soon as the molasses was exposed to the January chill, it began to harden. Imagine trying to swim through cold treacle. The deaths weren’t from drowning so much as suffocation, hypothermia, or being crushed by debris and syrup.

Witnesses described the scene like something out of Dante’s sticky circles of hell. Men and women shrieked while stuck in the goo. Horses thrashed and eventually stilled. Rescuers had to literally cut people free from the molasses using axes and chisels.

So how did this tank of doom come to exist? Well, the company had built it quickly during World War I to keep up with demand for industrial alcohol. No proper inspections. Shoddy construction. Rivets that popped out under pressure. The man who oversaw the tank’s design wasn’t even an engineer. He did, however, like to drink.

And then came the lawsuits. The Great Molasses Flood triggered one of the first class-action suits in Massachusetts. Over 100 plaintiffs lined up to sue the company. The case dragged on for six years. In the end, the company was found liable and paid out damages equivalent to about $100 million today. But did anyone go to jail? Of course not.

And yes, there is still debate about what caused the tank to fail that day. One theory says it was unusually warm for January (about 40°F), and a fresh delivery of warm molasses caused expansion inside the already stressed tank. Thermal expansion meets flawed design: the tank didn’t stand a chance.

Despite its farcical tone, The Great Molasses Flood helped usher in serious changes to engineering practices, zoning laws, and industrial regulation. Boston finally got wise to the idea that maybe massive metal tanks shouldn’t be placed next to densely populated areas without, say, proper structural testing.

It also launched an oddly devoted following. Every year, people gather in Boston to commemorate the tragedy. There’s a plaque. There are tours. It’s become a kind of sticky secular pilgrimage.

Some wild facts for your next dinner party (assuming you’re hosting engineers or very niche history buffs):

The molasses wave was powerful enough to lift a train car off its tracks. That’s not a metaphor. It flung a car from the elevated railway.

The flood created so much suction that in one case, a woman was pulled out of her shoes and trapped in molasses with only her head visible above the surface.

One poor horse was found with only its nose above the goo, still alive. Rescuers tried to save it. They couldn’t. Eventually they shot it, weeping.

Boston Harbour turned brown for months. Fish fled. Birds stopped coming. Sailors reported a sweet smell several miles out to sea.

The clean-up involved fire hoses spraying salt water. Crews had to use chisels and hot water to remove the syrup from cobblestones. Every boot, glove, and coat worn in the effort was ruined.

The molasses tank groaned for hours before it burst. Several workers said they heard metallic creaking. One person reported hearing “a deep rumble like thunder.” The company, naturally, ignored all this.

During the rescue efforts, the Red Cross converted a local police station into a triage centre. It filled quickly. Doctors complained their tools stuck to their hands.

A Boston Globe reporter at the time compared the scene to “the work of a giant baby who had spilled a tub of syrup and then danced in it in a tantrum.”

Some survivors were never found. A few victims were so buried in molasses and rubble that they weren’t located until days later.

An Italian immigrant named Nicola Zanfardino was blown through the air and pinned against a fence by the wave. He survived. His moustache, however, never recovered.

Police had to break into buildings to rescue people who were stuck to their floorboards. In several cases, furniture was fused to walls.

The disaster inspired a folk song titled “The Boston Molasses Flood,” which, surprisingly, is not as upbeat as the name suggests.

It took four months to clean the North End. And molasses got tracked throughout Boston by boots, wheels, and dogs for much longer. Legend says the Boston subway reeked of molasses for years.

When the court proceedings concluded, over 45,000 pages of testimony had been collected. It remains one of the longest civil cases in Massachusetts history.

The tank was never rebuilt. The lot where it stood is now a park. Children play where once molasses reigned in terror.

The flood has become a metaphor in American idioms. “Slow as molasses in January” took on a darker undertone. In this case, January molasses was terrifyingly fast.

Some historians speculate the flood has been underplayed because the victims were mostly immigrants—Italian and Irish, working-class, easy for newspapers to overlook in the long run.

One of the last survivors of the flood lived until 1998. She was four at the time and remembered being swept off her feet while playing outside.

Scientists have recreated the flood in laboratory conditions. Turns out, the wave shouldn’t have moved that fast. But gas bubbles from fermentation might have added extra force.

The Smithsonian once featured The Great Molasses Flood as an example of why material science and public safety matter. The irony was not lost on the curators.

To this day, no other city has ever suffered a similar molasses-based catastrophe. Which seems like a low bar, but still.

So there it is—a tragedy so bizarre it almost reads like satire. But The Great Molasses Flood wasn’t just some absurd blip in history. It left a sticky imprint on the city, on civil engineering, and on the ever-growing file of What Could Possibly Go Wrong. And if you ever find yourself strolling through Boston’s North End, pay attention the next time the air smells sweet. It might just be the ghosts of molasses past, wafting up to remind you that yes, syrup can kill.