The First Mobile Phone ’s Clunky Glory

The first mobile phone wasn’t just a gadget; it was a clunky, absurdly heavy brick that screamed, “Look at me, I’m the future!” Picture this: it’s 1983, and some bloke’s wandering New York with a device the size of a loaf of bread, making calls while everyone gawks like he’s holding a spaceship. That phone, the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X, kicked off a revolution, but let’s be real—it was also a bit of a laugh.

Let’s set the scene. The 1970s were a wild time—disco ruled, hair was big, and phones were stuck to walls. If you wanted to chat on the go, you either shouted across the street or lugged around a car phone, which was basically a radio with delusions of grandeur. Motorola, a company known for radios and walkie-talkies, decided to dream bigger. They weren’t alone—AT&T and others were sniffing around the idea of portable phones—but Motorola’s team, led by a chap named Martin Cooper, had a vision. Cooper, a proper tech romantic, wanted a phone you could carry in your pocket. Well, sort of. The DynaTAC didn’t exactly fit in your jeans, unless your jeans were the size of a duffel bag.

The story of the first mobile phone starts with a bit of cheek. On April 3, 1973, Cooper made the world’s first public mobile phone call, standing outside a Manhattan hotel. He rang up his rival at Bell Labs, Joel Engel, just to rub it in. “Joel, I’m calling you from a portable cellular phone,” he said, probably smirking. The phone wasn’t the DynaTAC yet—just a prototype—but it was a flex that set the stage. That call wasn’t just a chat; it was a gauntlet thrown down, a middle finger to the idea that phones had to be tethered. Motorola spent the next decade turning that prototype into something you could actually buy, and by 1983, the DynaTAC 8000X was ready to strut its stuff.

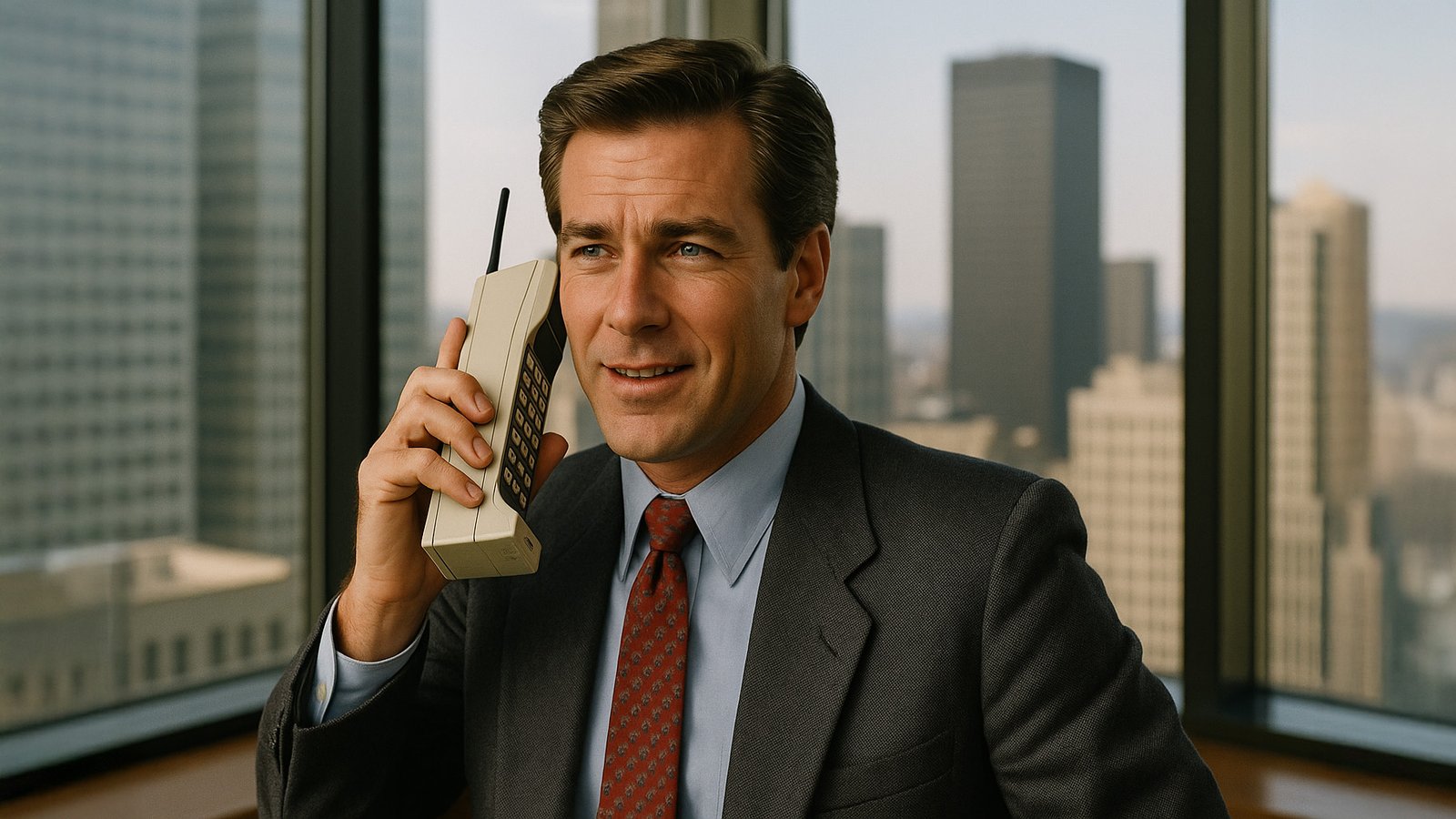

Now, let’s talk about this so-called “portable” phone. The DynaTAC weighed about 2.5 pounds, or roughly the same as a small dog. It was 10 inches long, not counting the antenna, which stuck out like a dodgy TV aerial. You could make calls for 30 minutes before the battery died, and recharging took(cartilage) took 10 hours. It cost £3000, which, adjusted for inflation, is like £10,000 today. Who was buying this thing? Rich folks, mostly—executives, Wall Street types, and anyone who wanted to look like they’d just stepped out of a sci-fi flick. The irony? This cutting-edge tech was less practical than a landline, but it screamed status. Carrying a DynaTAC was like waving a sign that said, “I’m loaded, and I don’t care if my arm’s falling off.”

The tech itself was a marvel, though. The DynaTAC worked on the AMPS (Advanced Mobile Phone System) network, a first-generation cellular system that used analogue signals. Unlike today’s phones, which bounce between towers seamlessly, early mobile networks had patchy coverage. You’d be chatting away, then—poof—static, or worse, a dropped call. The phone had a basic LED display for dialling numbers, and that was it. No texts, no apps, no Candy Crush. Just calls, and even those sounded like you were shouting into a tin can. Yet, for all its flaws, the DynaTAC was a proof of concept: mobile communication was possible, and that alone was mind-blowing.

Behind the scenes, building the DynaTAC was a slog. Motorola poured millions into R&D, wrestling with everything from battery life to signal interference. The cellular network itself was another hurdle. In the US, the FCC dragged its feet on allocating radio frequencies for mobile networks, worried about interference with existing systems. When they finally greenlit the spectrum in 1982, Motorola had to scramble to build base stations and infrastructure. It was like trying to invent the internet while also laying the cables for it. And let’s not forget the politics—AT&T, the telecom giant, wasn’t thrilled about Motorola muscling in on their turf. The whole thing was a messy, expensive gamble, and Motorola bet the farm on it.

What’s wild is how the DynaTAC captured the 80s zeitgeist. This was the era of big money, big hair, and big dreams. Wall Street, the movie, came out a few years later, with Gordon Gekko clutching a DynaTAC like it was his lifeline to capitalist glory. Pop culture ate it up—mobile phones became shorthand for power, wealth, and a kind of futuristic swagger. Never mind that using one felt like lugging a kettlebell to your ear. The DynaTAC wasn’t just a phone; it was a vibe, a symbol of a world obsessed with excess and ambition. The irony? Most users probably spent more time showing off the phone than actually talking on it.

The DynaTAC’s impact went way beyond its specs. It laid the groundwork for the mobile revolution. Motorola’s competitors—Nokia, Ericsson, and others—saw the potential and jumped in, driving innovation and slashing costs. By the late 80s, phones were getting smaller, cheaper, and less likely to give you a hernia. The shift from analogue to digital networks in the 90s made calls clearer and coverage better. Suddenly, mobile phones weren’t just for the elite. By the early 2000s, they were everywhere, and the DynaTAC’s DNA was in every flip phone and early smartphone. That brick started a chain reaction that turned phones into the pocket supercomputers we carry today.

But let’s not get too starry-eyed. The DynaTAC had its dark side. Early mobile phones raised health concerns—people worried about radiation from those chunky antennas. Studies were inconclusive, but the fear lingered, especially as phones became ubiquitous. Then there’s the social shift. Mobile phones made us reachable 24/7, which sounded great until you realised there was no escape from your boss or your mum. The DynaTAC planted the seeds of our always-on culture, where notifications ping us into oblivion. And don’t get me started on the environmental cost—those early batteries were toxic, and the rush to churn out new phones didn’t exactly scream sustainability. The irony’s thick: a device meant to connect us also set us up for stress, e-waste, and the occasional urge to yeet our phones into the sea.

Culturally, the DynaTAC was a game-changer. It reshaped how we communicate, work, and live. Before mobile phones, if you weren’t at home or in the office, you were off the grid. The DynaTAC made distance irrelevant—you could close a deal from a cab or call your mate from a beach. It gave us freedom, but also tethered us to expectations of constant availability. Businesses loved it; suddenly, execs could micromanage from anywhere. Relationships changed too—mobile phones made it easier to stay in touch, but also to ghost someone mid-call when the signal “dropped.” The DynaTAC didn’t just enable communication; it rewrote the rules of human interaction.

Looking back, the DynaTAC’s legacy is a mix of awe and amusement. It’s hard not to chuckle at its clunky design, like something a toddler would draw if you asked them to sketch a phone. Yet it was a bold leap into the unknown. Motorola didn’t just build a gadget; they sparked a paradigm shift. The mobile phone went from a rich man’s toy to a global necessity, with over 7 billion devices in use today. Every text you send, every TikTok you scroll, every Uber you book—it all traces back to that absurd brick. And yeah, it’s easy to mock its 30-minute talk time or its price tag, but in 1983, the DynaTAC was a moonshot, a bet that people would pay absurd money to talk on the go.

The DynaTAC also tells us something about human nature. We love shiny new things, even when they’re impractical. We’ll shell out for status symbols, then figure out how to make them useful later. The first mobile phone wasn’t perfect, but it didn’t need to be. It needed to exist, to prove a point, to start a conversation—literally and figuratively. And boy, did it deliver. It’s no coincidence that the 80s, with its obsession with excess, birthed this thing. The DynaTAC was the ultimate flex, a gadget that said, “I’m connected, I’m important, and I don’t care if this thing’s giving me a bicep workout.”

Fast-forward to today, and the DynaTAC feels like a relic from a parallel universe. Modern smartphones are sleek, powerful, and so integral to life that going a day without one feels like losing a limb. But every now and then, I wonder what Martin Cooper would make of it all. He dreamed of a world where anyone could call anyone, anywhere. He got that, and then some—along with selfies, emojis, and the joy of autocorrect turning “duck” into something else entirely. The DynaTAC’s story isn’t just about tech; it’s about ambition, hubris, and the weird, wonderful ways we keep reinventing ourselves. That brick might’ve been a joke by 90s standards, but it’s the punchline that keeps on giving, connecting us in ways we never could’ve imagined.