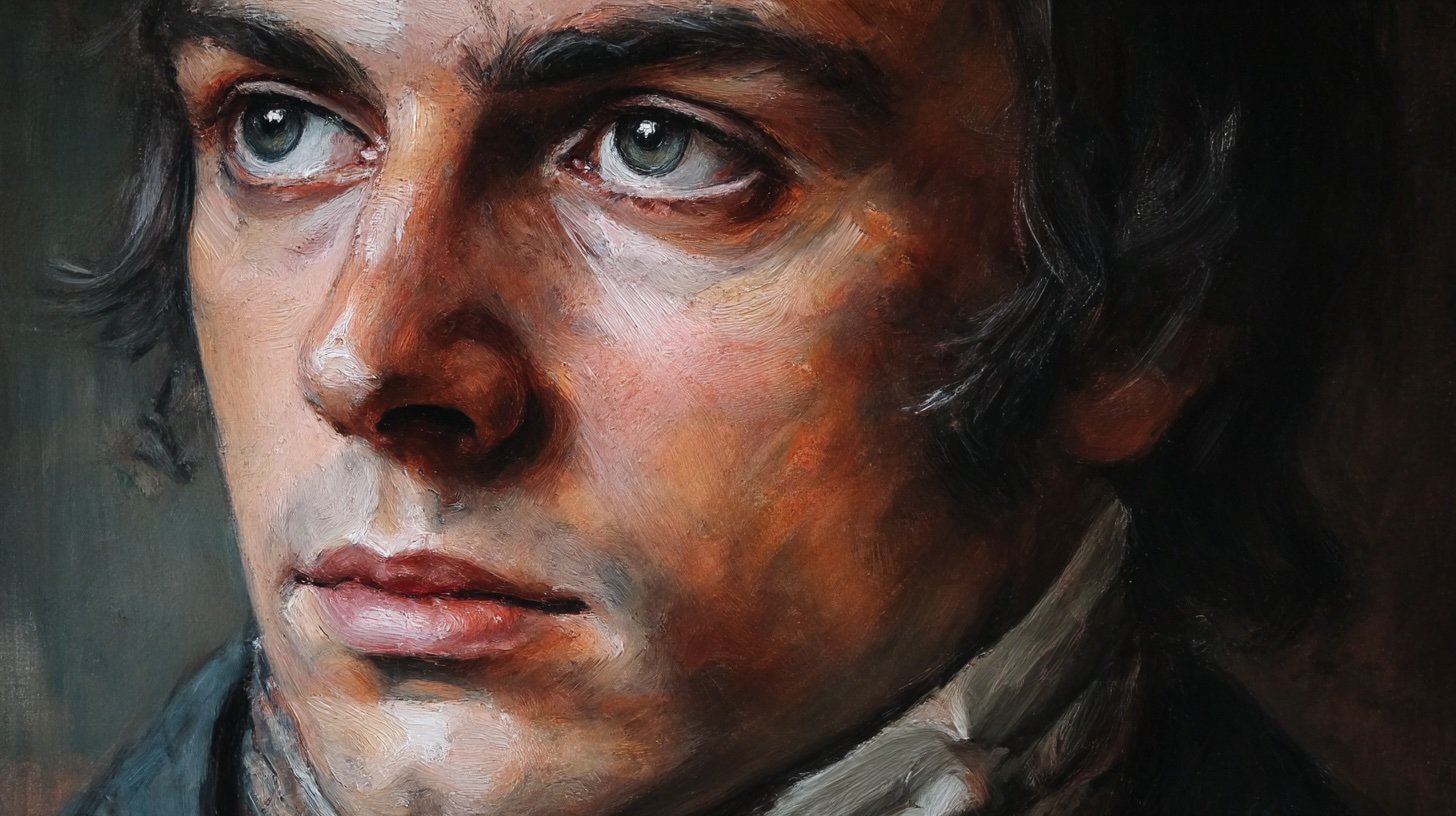

Robert Burns, Totally Unfiltered

You know the guy. Red hair, intense stare, romantic chaos trailing in his wake like a cloud of midges on a Highland summer evening. That’s right—Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet and resident literary heartthrob of the 18th century. And if you think he was just some dusty old bard churning out sentimental odes to mice and lasses, well, buckle in.

Robert Burns… Every schoolchild north of Gretna Green can recite “To a Mouse” in their sleep and will sigh dramatically when forced to dissect “Tam o’ Shanter” for homework, muttering about witches and warlocks like it’s an unwanted extra from Harry Potter.

Interestingly, he wasn’t meant to be famous. Burns started out as a farmer. A bad one. Not just bad—calamitously awful. His fields produced more poetic metaphors than they did oats. This poor lad’s farming career went the same way as most of his romantic relationships: short-lived, dramatic, and riddled with debt. His brother Gilbert once said Rabbie could barely tell a spade from a turnip. Even the cows looked unimpressed.

Speaking of romance, let’s get this out of the way early. Burns wasn’t so much a ladies’ man as he was a full-blown serial lover with a poetic licence for seduction. He fathered at least 12 children by four different women, and those are just the officially acknowledged ones. He probably inspired as many lullabies as love songs. His love life could have been a soap opera: mistresses, muses, jilted lovers, and more sighing than a Jane Austen adaptation marathon binge-watched by heartbroken teenagers.

He once wrote a poem as an apology to a woman’s father after getting her pregnant. Classy move? Maybe not. But definitely poetic. He didn’t do walk-of-shame so much as strut-of-verse. Some of his most heartfelt lines were dashed off on the backs of receipts, borrowed letters, and anything else that wasn’t nailed down. Rabbie never let paperwork get in the way of a good flirt.

Now, here’s where things get even more deliciously odd. When he wasn’t breaking hearts or penning lines about red, red roses, Burns worked as an exciseman. That’s right—a tax collector. The same guy who wrote impassioned odes to freedom and the plight of the common man was literally employed to collect the King’s coin. That’s Scottish irony in tartan trousers. Imagine Billy Bragg moonlighting for HMRC.

Burns had a real thing for egalitarianism, which made his tax-collector job even more awkward. He was a devoted fan of the American Revolution and, scandalously enough, admired the early ideals of the French Revolution. There were whispers his political leanings might get him sacked or worse, tossed into a damp Edinburgh cell with nothing but a goose quill for company. Being a radical in the 1790s wasn’t a great career move—unless your goal was to die young and become a myth. Which, as it happens, is more or less what occurred.

Let’s talk about his death, which is peak Burns. He died at 37, possibly from rheumatic heart disease, after a cocktail of overwork, alcohol, poverty, and what polite society might call “vigorous extracurricular activity.” His funeral took place on the same day his wife Jean Armour gave birth to his twelfth child. Yes, really. As the mourners filed out of the churchyard, the midwife was still wiping down the newborn. You couldn’t script it better unless you were aiming for a tragicomic stage play.

Oh, and speaking of stage plays—Robert Burns nearly ended up in Jamaica. Yes, that Jamaica. Broke, demoralised, and ready to chuck the plough for good, he almost boarded a ship to work as a bookkeeper on a slave plantation. The only reason he didn’t go was because his first published book in 1786, the Kilmarnock Edition, made him an overnight celebrity. And thank goodness, because “A Man’s a Man for A’ That” hits a little differently when you imagine it written between sugar-cane ledgers and plantation ledgers.

He also had a compulsive obsession with folk songs. The man collected and edited hundreds of traditional Scottish tunes, sometimes rewriting them so heavily you’d need a detective to find the original tune buried beneath all the lyrical flourishes. He basically acted as Scotland’s unofficial Spotify playlist curator—except with fewer royalties, more moralising, and a lot more bagpipes. He collaborated with music collectors like James Johnson and George Thomson, turning ballads into national treasures with a cheeky wink and a dram in hand.

Burns was also weirdly obsessed with his own legacy. He knew he’d be remembered. He hinted at it, wrote about it, basically carved it into his own tombstone with every poem. There’s a kind of endearing arrogance in knowing you’ll be immortal. Not to mention deeply practical, considering how often he skirted financial ruin, legal scandal, and romantic chaos. He practically haunted his own future biographers.

And if you’ve ever heard of Burns Night, the annual whisky-soaked poetry bacchanal that involves addressing a haggis like it’s a Roman emperor, that’s all his doing. Burns Night started just a few years after his death and has since become the only global event that combines sheep’s organs and sonnets in perfect harmony. There are formal addresses to the haggis, recitals of his verse, toasts to the immortal memory, and more kilts than an Edinburgh wedding in July.

Oh, and he also wrote the world’s most famous New Year’s song. Yep, “Auld Lang Syne” is Burns through and through. Originally an old Scottish folk tune, Rabbie gave it new words, new life, and unknowingly cursed us all to awkward hand-holding singalongs every 31st December. It’s been translated into dozens of languages and butchered by every cover band on Earth.

Did you know there’s a crater on Mercury named after him? That’s right. NASA decided the Bard of Ayrshire deserved a celestial monument. The man whose poems celebrated humble ploughmen and bonnie lasses now has a permanent presence on another planet. Interstellar irony at its finest. Somewhere in space, a robot might be rolling over Burns’s name while transmitting scientific data.

Here’s another pearler—his birthday, 25 January, is now more celebrated in Scotland than that of Saint Andrew, the actual patron saint of the country. A poet who wore second-hand breeches and dined on boiled tatties has eclipsed a canonised saint. That’s poetic justice served with neeps and tatties.

And finally, he was once voted the greatest Scot of all time. In a poll conducted by STV, Burns beat William Wallace, Alexander Graham Bell, and even Sir Sean Connery. The man literally beat James Bond. Try topping that with a sonnet. Bagpipes might’ve been involved in the victory, but the people had spoken—and they chose the ploughman poet.

There’s even a Robert Burns statue on every continent except Antarctica. You’ll find his granite likeness in cities from Sydney to San Francisco, always mid-recitation or gazing wistfully into the middle distance. It’s like Pokémon Go for literary romantics.

So next time someone drones on about literary heritage or wheels out some dreary dead poet to suck the joy out of language, remember Robert Burns—the romantic, chaotic, whisky-drenched rockstar of rhyme. And raise a glass to the most peculiar poet ever to rhyme “luve” with “dove” and make it sound like an act of war.

Slàinte, Rabbie. You glorious, impossible, scandalous legend, may your ghost forever haunt the hearts of romantics and rascals alike.