Ren: Why Confucius Kept Changing His Mind About This One Big Idea

Imagine trying to pin down a concept so profound that even the philosopher who championed it refused to give it a straight definition. That’s precisely what we’re dealing with when we talk about Ren, the cornerstone of Confucian philosophy. Confucius, the sage who lived in 6th century BCE China, had this rather cheeky habit of answering questions about Ren differently depending on who asked. One student might hear that it meant “loving others,” whilst another would be told it required courage and freedom from worry. Talk about keeping your pupils on their toes.

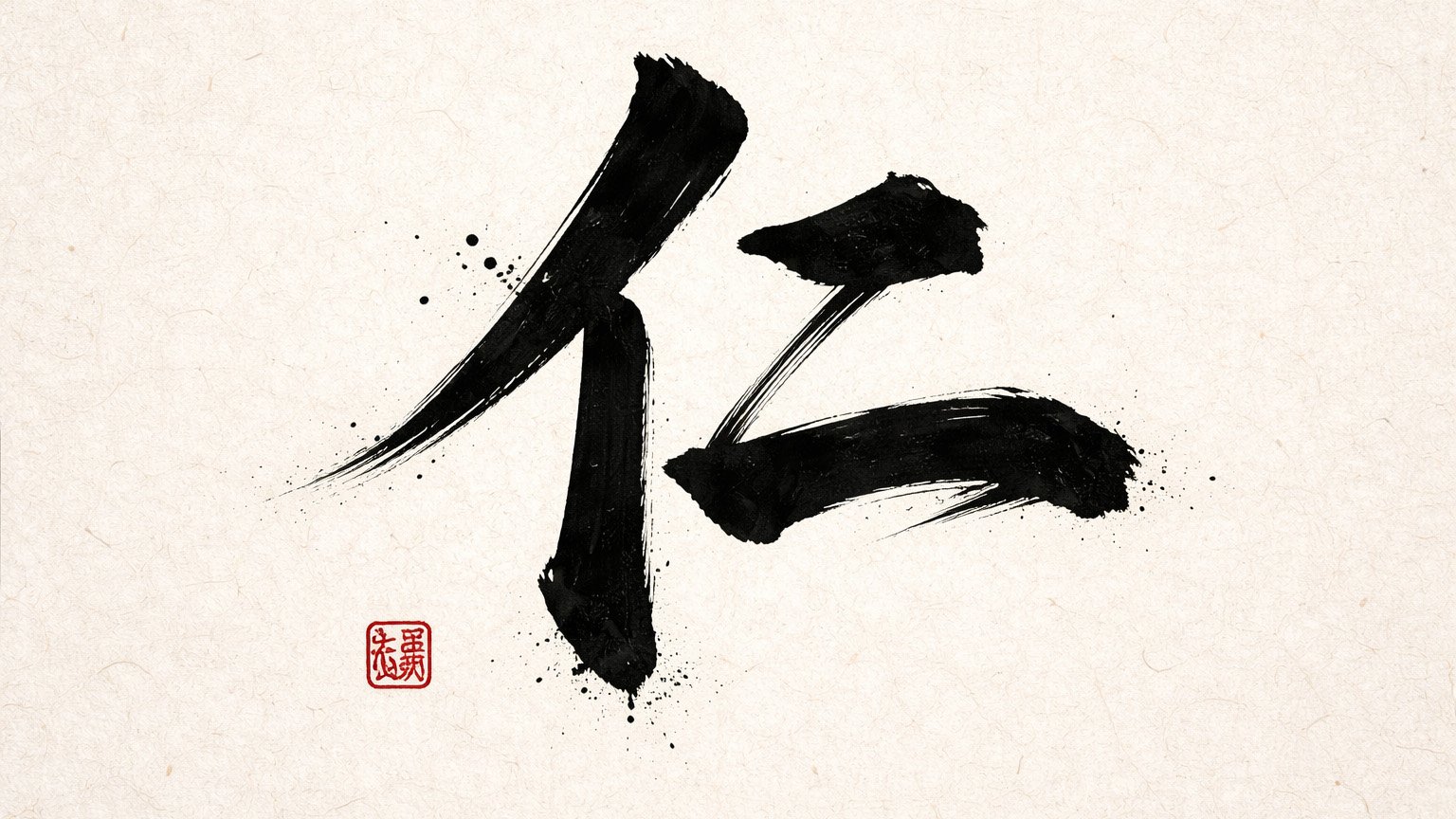

The Chinese character for Ren itself offers a brilliant clue to its meaning. It combines two symbols: the character for “person” and the character for “two.” Scholars have had an absolute field day interpreting this, but most agree it points to something essential about human relationships. We’re talking about what happens between people, the space where humanity actually lives and breathes. Some translations call it “benevolence” or “humaneness,” but these English words barely scratch the surface of what Confucius was getting at.

What makes Ren particularly fascinating is that Confucius elevated it from a rather pedestrian term meaning general kindness into the highest virtue a person could achieve. Before him, the word existed with modest ambitions. Nevertheless, he transformed it into something far more ambitious: the very essence of being human. According to the Master himself, Ren encompasses benevolence, trustworthiness, courage, compassion, empathy, and reciprocity all rolled into one magnificent package. No wonder he couldn’t just rattle off a quick definition.

The philosophical brilliance of Ren lies in its practical nature. This isn’t some abstract concept floating about in the clouds. Instead, it manifests itself in everyday human interactions. Confucius believed that the most emotionally charged human relationship—a helpless infant with its caring parent—served as the template for understanding Ren. That love, that instinctive desire to protect and nurture, represents the seed from which all human virtue grows. Furthermore, Confucius taught that one cultivates Ren through proper ritual and behaviour in daily life. It’s not enough to feel benevolent thoughts; you’ve got to actually practise treating people well.

Now, here’s where things get interesting for us modern folks. Confucius gave us what’s essentially an early version of the Golden Rule, though his formulation has a slightly different flavour than the one many of us know. Rather than the positive “do unto others,” Confucius offered the negative formulation: “Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire.” When his student Zi Gong asked if there was a single word to guide one’s entire life, Confucius replied with “shu”—reciprocity or empathy. The idea being that if you use yourself as a measuring stick for understanding others’ feelings and needs, you’re well on your way to practising Ren.

This negative version of the Golden Rule might seem like a subtle distinction, but it’s actually quite clever. Telling someone to actively do good things for others can be tricky because people want different things. However, avoiding the behaviours and treatment you yourself would hate? That’s a pretty universal starting point. Confucius recognised that empathy—putting yourself in someone else’s shoes—serves as the foundation for moral behaviour. Consequently, practising Ren means constantly asking yourself how your actions affect others, then adjusting accordingly.

The relationship between Ren and other Confucian virtues creates an intricate web of moral philosophy. Li, or ritual propriety, acts as the outward expression of Ren. Think of it this way: Ren is your internal moral compass whilst Li provides the specific behaviours and customs that help you express that inner virtue. You can’t just feel benevolent; you need to know how to properly show respect through appropriate rituals and behaviour. Moreover, Yi (righteousness), Zhi (wisdom), and Xin (integrity) all interconnect with Ren, creating a comprehensive system for ethical living.

Mencius, who came after Confucius, added his own flavour to the concept. He argued that Ren springs from a natural feeling of compassion within the human heart. His famous example involved witnessing a child about to fall into a well—anyone would feel immediate concern for the child’s safety, even if they didn’t act on it. This spontaneous feeling of compassion represents the “sprout” of Ren. Through cultivation and practice, that sprout can grow into full-blown benevolence extending to all humanity. Mencius believed humans are fundamentally good, and Ren simply needs proper nurturing to flourish.

But let’s not pretend Confucian philosophy sailed through history without criticism. The concept of Ren, whilst beautiful in theory, got tangled up with some rather problematic applications. Traditional Confucian society wasn’t exactly a poster child for equality. Women found themselves relegated to domestic spheres, social hierarchies remained rigid, and that whole “filial piety” thing could be used to justify some seriously oppressive relationships. Critics during China’s New Culture Movement and Cultural Revolution lambasted Confucianism for creating a society that valued blind obedience over critical thinking.

The feminist critique of Confucianism raises valid concerns. Although Confucius himself never explicitly stated that Ren was gender-specific, the Five Relationships he championed (ruler-subject, father-son, husband-wife, elder brother-younger brother, friend-friend) were notably hierarchical. Four out of five involved a superior and a subordinate. Women got the short end of the stick in practice, even if the theory didn’t necessarily demand it. Modern scholars debate whether Ren itself is sexist or whether patriarchal societies simply hijacked a good idea for bad purposes.

Then there’s the ongoing academic debate about how to translate and interpret Ren in contemporary contexts. Some philosophers suggest “care” might be more appropriate than “benevolence,” linking Confucian ethics to modern care ethics. Others argue about whether Confucius meant Ren as a specific virtue or as an umbrella term encompassing all virtues. These debates might seem academic, but they matter because they determine how we apply ancient wisdom to modern problems.

Surprisingly, Ren has found new relevance in today’s business world. Leadership experts increasingly tout Confucian principles for ethical management, particularly in our rather ethically challenged corporate landscape. The emphasis on treating employees with empathy, leading by moral example, and prioritising stakeholder wellbeing over pure profit sounds rather refreshing, doesn’t it? Companies are discovering that benevolent leadership—caring genuinely about people rather than treating them as cogs in a machine—actually produces better results.

The concept of Ren challenges modern individualism in fascinating ways. Western culture tends to celebrate the autonomous individual achieving success through personal effort. Ren, however, reminds us that we’re fundamentally relational beings. Our humanity doesn’t exist in isolation; it emerges through our interactions with others. You can’t cultivate Ren by yourself on a mountaintop. You need other people to practice benevolence towards, to empathise with, to engage in reciprocal relationships with.

Particularly brilliant about Ren is its emphasis on internal cultivation leading to external action. It’s not enough to follow rules mechanically or perform good deeds for show. The virtue must be sincere, emerging from genuine care for others. Confucius stressed that ritual practice without sincerity becomes empty performance. Your “inner feelings and outer demeanours” need to align. This insistence on authenticity feels remarkably modern, doesn’t it? We’re surrounded by performative virtue signalling these days; Confucius would have rolled his eyes at it 2,500 years ago.

Practising Ren in daily life needn’t be complicated. Start small: treat service workers with respect, listen actively when someone shares their troubles, help a colleague without expecting anything in return. These simple acts embody the principle of treating others as you’d wish to be treated. Additionally, Ren involves self-reflection—regularly examining your own behaviour and asking whether you’re living up to your values. Confucius himself reportedly engaged in constant self-examination, always striving to improve his moral character.

The beauty of Ren lies in its accessibility. Confucius insisted that anyone could cultivate this virtue regardless of social status. Whilst traditional interpretations got bogged down in class hierarchies, the core idea remains democratic: every human being possesses the capacity for benevolence and can work towards achieving it. You don’t need wealth, power, or special talent. Simply put, commitment to treating others with genuine care and respect is all that’s required.

Looking at our current global challenges—polarisation, inequality, environmental destruction—the principle of Ren offers something valuable. Imagine if leaders actually prioritised human wellbeing over short-term gains. Consider if we approached disagreements with empathy rather than hostility. Think about what might happen if we recognised our fundamental interconnectedness rather than retreating into tribalism. These questions aren’t naive; they’re essential. Moreover, they’re precisely the questions Confucius was asking 2,500 years ago in his own tumultuous era.

The concept hasn’t lost its power simply because it’s ancient. Perhaps its very antiquity proves its worth. Human nature hasn’t fundamentally changed since Confucius walked the earth. We still struggle with selfishness, cruelty, and indifference. We still need reminding that our humanity depends on how we treat others. Ren provides that reminder, dressed in 2,500-year-old robes but speaking to something timeless.

So next time you’re facing a difficult decision involving other people, try channelling a bit of Confucian wisdom. Ask yourself: would I want to be on the receiving end of this action? Am I treating this person with genuine care and respect? Am I considering their wellbeing alongside my own interests? These questions embody Ren in practice. Furthermore, they’re questions our world desperately needs more people to ask.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.