Polymath Lifestyle: Why Living Wide Still Beats Living Fast

Polymath lifestyle sounds like something invented by a modern productivity guru with a podcast microphone and a standing desk, yet the idea is far older than the calendar reminders trying to package it today. At its core, polymath lifestyle simply means organising your life around curiosity, range, and synthesis rather than choosing one narrow lane and decorating it forever. It is not about collecting random skills like souvenirs. It is about letting different ways of thinking rub against each other until something useful, strange, or quietly original appears.

Long before anyone worried about personal branding, polymathy was the default. Aristotle did not wake up one morning and decide to diversify his skillset. Knowledge had not yet been chopped into polite academic departments. Philosophy, biology, politics, ethics, and poetry sat at the same table, often arguing. Living widely made sense because the world itself refused to behave neatly.

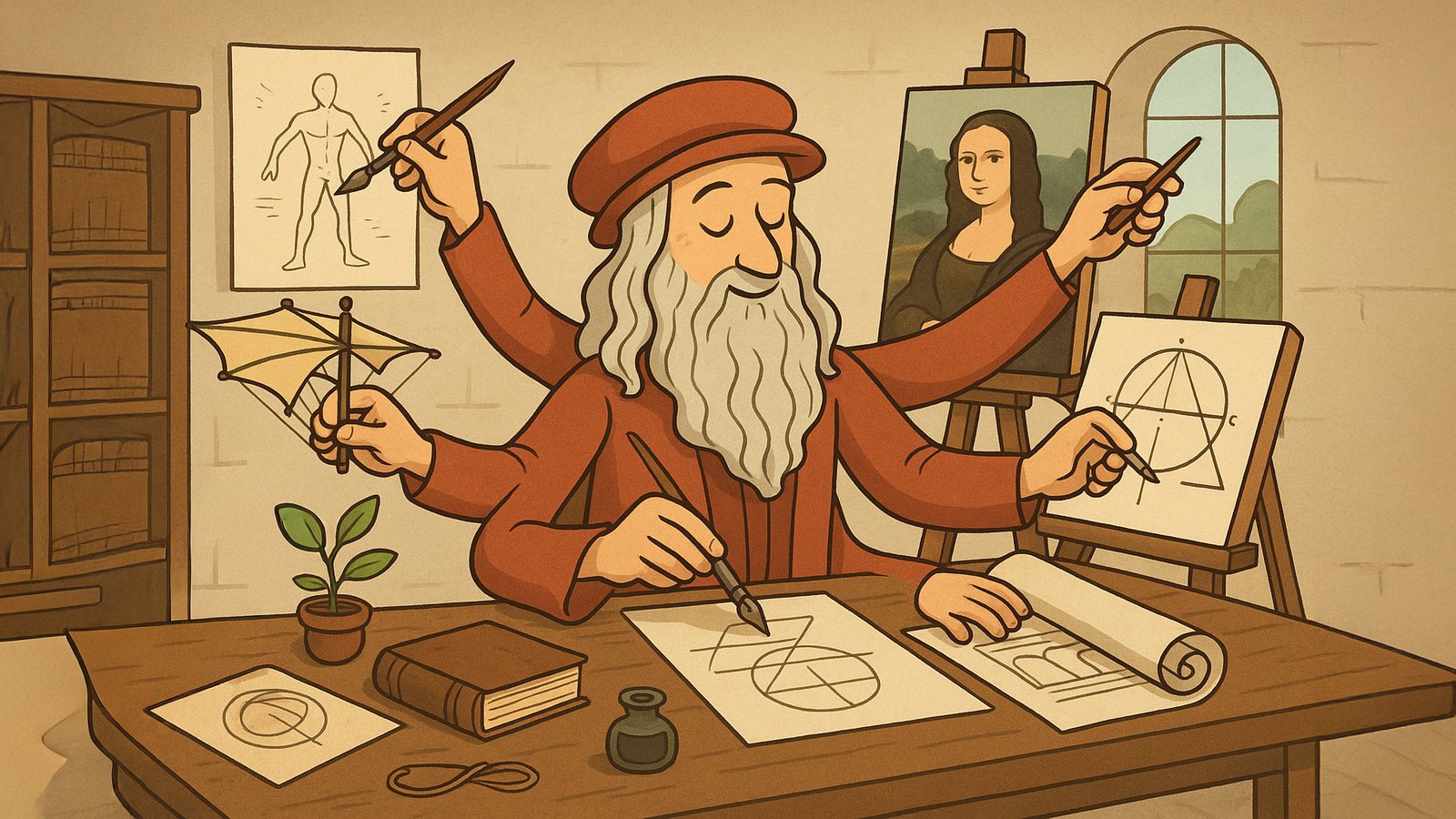

The Renaissance turned this natural condition into an aspiration. Leonardo da Vinci sketched flying machines next to anatomical studies and stage designs, not because he wanted to impress future museum visitors, but because drawing was how he thought. Painting sharpened his science. Engineering fed his art. The polymath lifestyle was not a lifestyle choice. It was a working method.

Things shifted once the industrial age arrived. Complexity exploded, factories multiplied, and specialisation began paying the rent. Knowledge stopped being a shared commons and became professional territory. Universities drew borders. Careers straightened into ladders. The polymath did not disappear, but became inconvenient. A person who did many things well suddenly looked unfocused in a system built to reward one thing extremely well.

This is where the modern tension begins. We live in a world that publicly celebrates innovation, creativity, and “thinking outside the box”, while privately promoting job descriptions that fit neatly into boxes. The polymath lifestyle survives in the cracks between those expectations.

Today, polymath lifestyle rarely looks like a single grand career. It looks like portfolio lives, hybrid identities, and odd combinations that make HR software nervous. Strategy consultants who photograph cities at dawn. Engineers who write essays on ethics. Designers who study behavioural economics for fun and then quietly apply it at work. The common thread is not chaos, but integration.

A genuine polymath lifestyle relies on movement between fields, not permanent multitasking. People who live this way tend to cycle through phases. One season might belong to writing, another to learning a new technical skill, another to teaching or advising. Depth still matters, but it rotates. Obsession moves, rather than vanishing.

This is where the first myth falls apart. Polymaths are often accused of lacking focus. In practice, many show extreme focus, just not forever in one place. Leonardo abandoned projects, yes, but not because he was distracted. He followed problems until they stopped teaching him anything new.

Another popular myth paints polymaths as gifted dabblers, gliding effortlessly across disciplines. Historical reality looks far messier. Darwin spent decades observing, cataloguing, and doubting before publishing. Goethe rewrote and argued with himself endlessly. Polymathy usually involves sustained frustration, long apprenticeships, and the humility of being a beginner more than once in adulthood.

The polymath lifestyle also tends to be far more structured than people expect. Many famous polymaths ran rigid daily routines. Morning walks, strict reading hours, obsessive note-taking. Structure creates the freedom to explore without collapsing into distraction. Chaos looks romantic in hindsight. Lived chaos rarely produces much of interest.

One of the quieter pleasures of polymath living lies in transfer. A metaphor from architecture suddenly solves a business problem. A musical structure reshapes a presentation. An insight from psychology reframes a technical failure. This cross-pollination is where polymaths quietly outperform specialists, not by knowing more, but by connecting more.

This ability to translate between worlds has real economic value, even if it resists tidy metrics. Many modern polymaths end up in roles that sit between disciplines rather than inside them. Strategy, product leadership, creative direction, teaching, advising. They become interpreters. They ask questions specialists stop asking because everyone assumes the answers already exist.

Of course, polymath lifestyle is not without controversy. Critics argue that it romanticises breadth at the expense of mastery. In fields like medicine or structural engineering, this criticism holds weight. Nobody wants a broadly curious brain surgeon. Polymathy works best where synthesis, judgement, and context matter more than procedural perfection.

Another uncomfortable truth is privilege. Many historical polymaths benefited from wealth, patronage, or social position that bought them time. The idea that anyone can effortlessly live widely ignores rent, childcare, and burnout. Modern polymath lifestyles often require careful design, not blind enthusiasm. Constraints must be acknowledged rather than waved away.

There is also a branding problem. The word polymath has been stretched thin. When everyone becomes a polymath by adding hobbies to a LinkedIn bio, the concept loses meaning. Historically, polymaths produced work that others found useful, provocative, or foundational. The label arrived later. It was not self-assigned.

Despite this dilution, the underlying impulse refuses to disappear. The problems shaping modern life are stubbornly interdisciplinary. Climate change ignores academic boundaries. Artificial intelligence raises ethical, technical, legal, and cultural questions simultaneously. Organisations struggle not because they lack specialists, but because those specialists struggle to talk to each other.

This is where polymath lifestyle regains quiet relevance. Not as rebellion, but as response. Living widely becomes a practical adaptation to complexity rather than a romantic ideal.

At a personal level, polymath living often provides psychological resilience. When identity is spread across several domains, failure in one area hurts less. Curiosity becomes a renewable resource. Learning stays playful rather than performative. Work stops defining the entire self.

There is also an ageing angle rarely discussed. As careers lengthen and people change roles multiple times, polymath habits help prevent stagnation. Skills acquired for curiosity often become unexpectedly useful later. The side interest becomes the bridge.

The polymath lifestyle does demand trade-offs. You will progress more slowly in any single domain than someone who never looks sideways. Recognition may arrive late, if at all. Explaining what you do can feel awkward at dinner parties. These costs are real and should not be sugar-coated.

Yet the rewards are equally tangible. Perspective deepens. Conversations improve. Pattern recognition sharpens. You start seeing systems rather than events. History stops being a collection of dates and becomes a laboratory of human behaviour.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of polymath living is that it resists optimisation. It does not chase maximum efficiency. It values detours. It allows wasted afternoons that later turn out not to be wasted at all. In a culture obsessed with measurable output, this resistance feels quietly radical.

Polymath lifestyle is not about becoming extraordinary at everything. It is about refusing to become small. It invites a life built around questions rather than titles, connections rather than ladders, and meaning rather than neatness. That has always made institutions uneasy.

Which may be the best argument in its favour.