Plato’s Cave: Why We Still Mistake Shadows for Reality

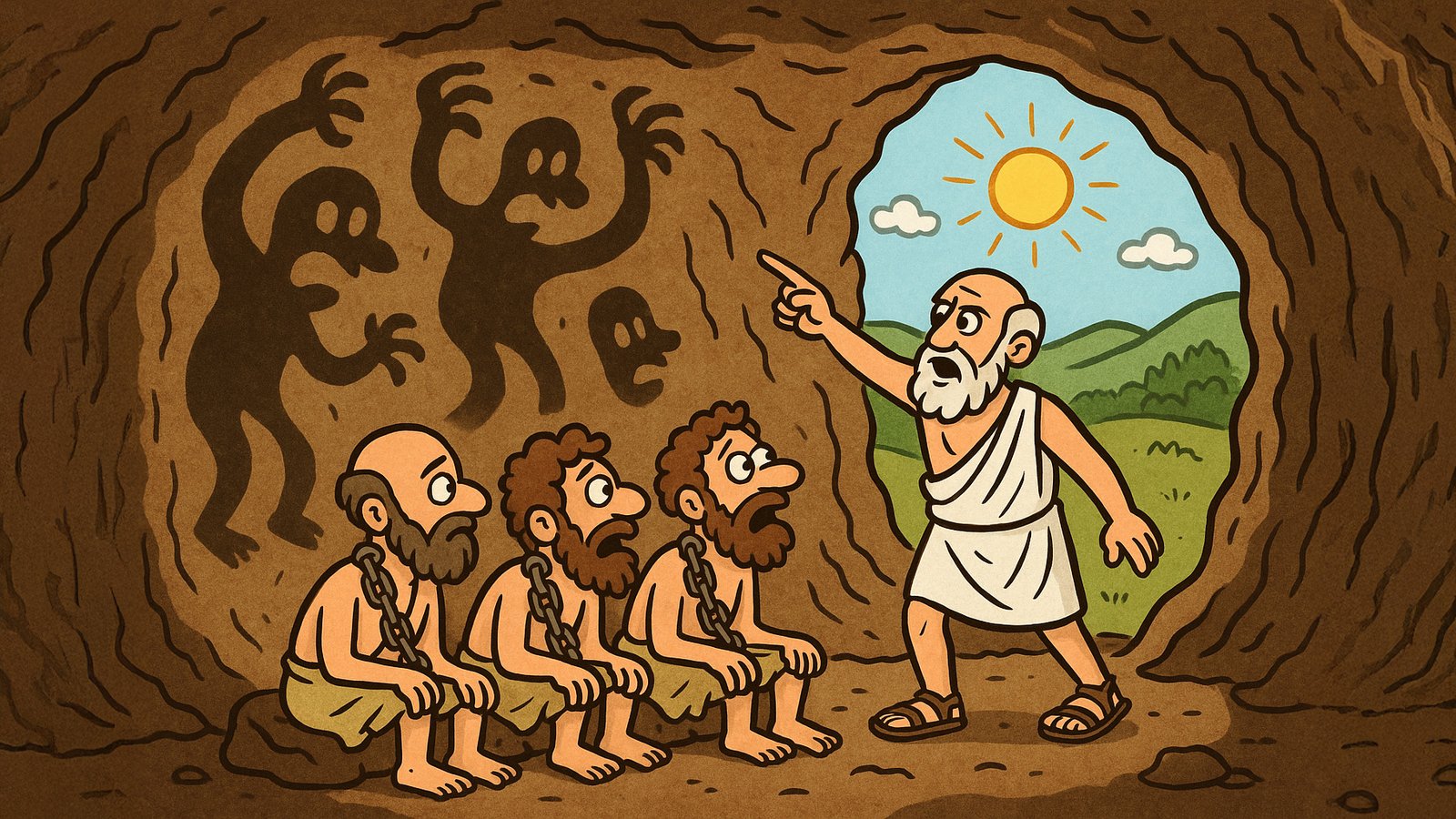

Plato sketched a scene so strange that it still grabs people two and a half millennia later: a dark cave, a row of people who never turn their heads, and a parade of shadows flickering on a wall. It sounds like a setup for experimental theatre, yet he used it to explain why humans cling to illusions and why anyone who breaks free from them ends up looking a bit mad to everyone else. Classical philosophy rarely gives you imagery this vivid; Plato, for once, seemed in a storytelling mood.

Imagine the cave not as some dusty Greek grotto, but more like an odd basement cinema nobody asked to visit. People sit chained, unable to move or turn, condemned to watch the same shadowy projections forever. None of them knows those shadows are a second‑hand reality, just silhouettes cast by objects passing behind them. They debate the patterns, classify them, make predictions, argue about which shadow will glide by next. It becomes a whole intellectual ecosystem based on nothing but guesswork about shapes.

Life goes on quite peacefully until one of them somehow slips free. Freedom, as Plato hints, feels awful at first. The poor fellow turns around and sees a fire blazing behind him. His eyes water. The shapes he trusted for so long suddenly look flat compared with the real objects casting them. Everything he believed collapses in a moment of painful clarity. Breaking habits is rarely pretty, and Plato captured that discomfort with a kind of gentle sarcasm.

This newly liberated cave‑dweller stumbles out of the cave and into daylight. It blinds him. The real world comes at him far too fast: colours, textures, sky, sunlight, the awkward discovery that trees actually exist rather than merely wobble on a wall. He needs time to adjust. Nothing in the cave prepared him for this explosion of detail. It’s the philosophical equivalent of swapping an old black‑and‑white telly for a 4K OLED in a single afternoon.

Eventually, though, he starts seeing properly. Water reflects light. Animals wander about on their own business. People have actual faces. Truth sits outside the cave, not in shadow form but as the world itself. Plato quietly suggests that this kind of enlightenment changes you permanently. Once you’ve seen the real world, it’s nearly impossible to find shadows convincing again.

But the story doesn’t end with this personal revelation. The newly enlightened man does something noble and slightly foolish: he goes back. Plato probably chuckled when he wrote this part, because the homecoming happens exactly as anyone who’s tried to share an uncomfortable truth might expect. He returns to the cave desperate to help the others see what he has seen, only to find that his eyes—accustomed to sunlight—can’t handle the darkness anymore. He stumbles, fumbles, squints. The prisoners laugh. They think enlightenment makes people clumsy.

Then comes the real sting: when he explains that the shadows are not reality at all, that there’s an outside world beyond anything they’ve imagined, nobody believes him. They feel quite satisfied with the shadows. They’ve studied them, grown fond of them, built whole identities around them. Someone claiming that everything they know is merely a flicker on a wall sounds like a dangerous lunatic. Plato didn’t mince words on this point: people do not appreciate having their assumptions questioned.

The allegory works on several levels. At its simplest, it’s about education. Real learning isn’t about memorising shadows; it’s about turning your head, leaving the familiar, and tolerating a bit of disorientation until your eyes adjust to truth. Plato suggests that most people never make that turn. They live contentedly in the cave, reciting old ideas they never examine.

On another level, it’s about society and power. Those who control the shadows—the stories, images, and narratives everyone consumes—hold influence. The cave becomes a metaphor for any environment where people mistake symbols for reality. You can swap Plato’s shadows for modern screens and the point remains painfully fresh. He just got there a couple of thousand years early.

It also hints at something personal. Everyone carries a cave somewhere inside them: a set of beliefs absorbed without question, a worldview shaped by habit or comfort. Escaping it usually requires a jolt, an uncomfortable moment when the familiar no longer convinces. Plato doesn’t pretend it’s easy. The bright light hurts, the first steps wobble, and returning to old company becomes awkward. But he also suggests it’s worth it.

One of the striking features of the story is how little Plato cares about the cave’s physical realism. He knew nobody would chain people in a cavern to gaze at shadows for decades. The scene is a psychological portrait, not a historical claim. By exaggerating the setting, he highlights how absurd our own illusions can look from the outside.

The freed prisoner’s return to the cave often sparks debate. Some read it as civic duty: once you’ve seen truth, you owe it to others to try to help them see it too. Others notice the darker interpretation: those who challenge comfortable illusions face hostility, suspicion, and sometimes danger. Plato had a front‑row seat to political upheaval in Athens, and the allegory reflects his unease about what happens to people who question the status quo too boldly.

There’s also an existential flavour to the whole thing. Plato nudges readers to ask whether they’re still sitting in the cave without realising it. It’s not a judgemental question; it’s more of an invitation. What assumptions have you never re‑examined because they felt too familiar? What truths might sit just outside your line of sight? The allegory doesn’t answer these questions—it merely sets up a scene vivid enough that people keep asking them centuries later.

Modern thinkers often reinterpret the cave in playful ways. Some see it as media criticism, where screens offer endless shadows that feel more comforting than reality. Some view it as commentary on social bubbles, information silos, or even echo chambers where people rarely encounter anything beyond the shadows they already agree with. The flexibility of the metaphor explains its staying power.

If you strip everything down, the message becomes remarkably accessible. People often live with simplified versions of the world, and moving towards something more true involves discomfort. Those who make that transition don’t always receive applause when they come back with news. But Plato hints that the freedom to see things clearly outweighs the awkwardness of explaining it to others.

The cave, then, isn’t a place but a habit. The shadows aren’t illusions forced upon us by malicious puppeteers; they’re comfortable stories we accept because they demand so little effort. The fire behind us is the warmth of familiarity. Walking out into sunlight is the unsettling moment when we realise the world is bigger, messier and far more interesting than the silhouettes we believed for so long.

Plato leaves the ending open. He never mentions whether more prisoners escape or whether the cave community continues debating shadows until the end of time. The ambiguity feels intentional. He wasn’t aiming for a neat moral but a wake‑up call disguised as a fable. He wanted readers to notice their own caves and imagine the possibility of stepping outside.

What makes the story charming is its simplicity. A cave, a fire, a wall, a handful of people chained in place. From these sparse ingredients Plato built a metaphor spacious enough to hold ideas about truth, perception, politics, psychology and self‑discovery. It’s no surprise that pupils still meet this allegory long before tackling the rest of his dense philosophy. It’s accessible, almost cinematic, and invites interpretation without demanding prior training.

Perhaps that’s why the allegory persists today. People still sense the tug between comfort and curiosity. They still argue about shadows. They still follow those rare individuals who step outside and come back wild‑eyed with new stories, and they still mistrust them. Plato captured something enduring about human behaviour, wrapped in a tale simple enough to retell in a café without losing its punch.

The next time someone mentions the cave, it’s worth remembering that the heart of the story isn’t the darkness but the moment when someone stands up and turns around. That small movement changes everything. Plato loved the idea that enlightenment begins not with dramatic revelation but with the decision to shift perspective. The rest—fire, sunlight, bewilderment, clarity—follows naturally.

So the cave continues to haunt imagination because it mirrors everyday life. People build worlds out of shadows. Sometimes they escape them. Sometimes they go back to help others. Most importantly, they discover that real understanding starts with the courage to look beyond the familiar wall and walk, blinking and confused, towards the light.