Osteoporosis and the Price of Comfort in Modern Life

Osteoporosis sounds like a condition reserved for hospital corridors and pharmaceutical leaflets. Yet in practice, it begins much earlier and far closer to home. It forms in kitchens, offices, cars, and sofas. Gradually, it takes shape through habits that feel harmless, even sensible, while quietly reshaping how skeletons behave.

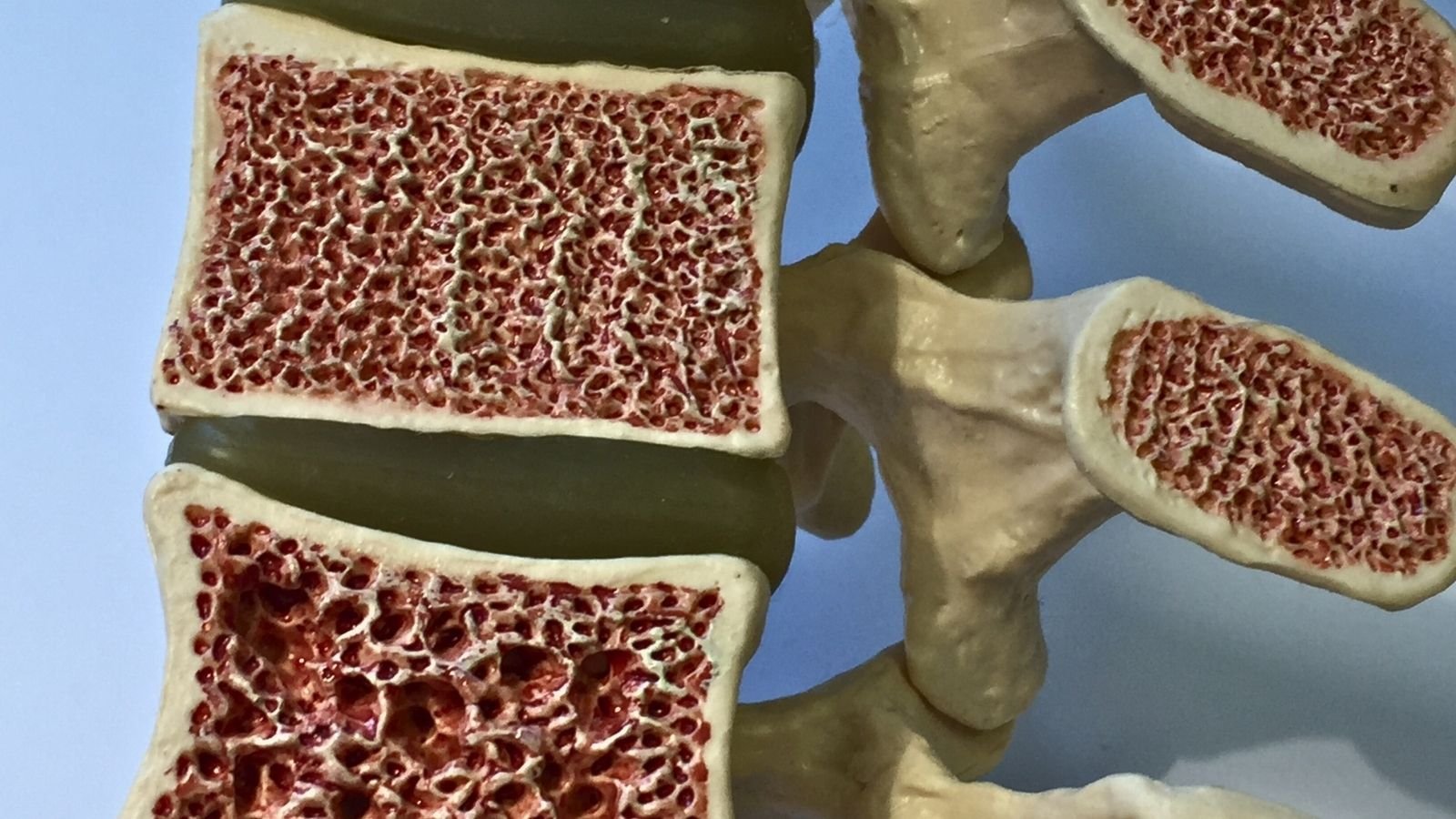

For most of human history, bones lived busy lives. They carried bodies across uneven ground, absorbed impact, resisted gravity, and adapted constantly to physical stress. As a result, bone tissue evolved to expect pressure. Without it, the skeleton does not protest. Instead, it adjusts by becoming lighter, thinner, and easier to break. Osteoporosis is not sudden failure; rather, it is long-term adjustment to modern conditions.

Modern life, however, treats bones as passive infrastructure. We rarely notice them unless something goes wrong. Muscles get attention, skin gets attention, and even gut bacteria enjoy a moment in the spotlight. Meanwhile, bones sit quietly in the background, assumed to be solid and permanent. That assumption no longer holds.

Sedentary work now defines the physical posture of adulthood. Chairs dominate the day, while screens anchor attention. Consequently, movement gets compressed into brief, deliberate episodes that must compete with meetings, deadlines, and exhaustion. From a skeletal perspective, this matters deeply. Bones respond to repeated load, not occasional enthusiasm. Therefore, they strengthen when muscles pull on them regularly and weaken when those signals fade.

An hour at the gym does not fully undo ten hours of sitting. Instead, bone cells react to the most frequent message they receive. When that message says stillness, they economise. Over time, density declines because strength appears unnecessary. Eventually, this becomes structural fragility rather than simple deconditioning.

Standing desks help posture; however, they rarely recreate the varied loading bones evolved to expect. Walking on flat floors, lifting light objects, and avoiding impact reduce the diversity of stress that once kept skeletons resilient. Moreover, daily life itself has become frictionless. Lifts replace stairs, cars replace legs, and deliveries replace carrying.

Indoor living compounds the problem further. Human bones rely on vitamin D to absorb calcium efficiently. Vitamin D synthesis depends largely on sunlight exposure, yet modern routines keep most people inside during daylight hours. At the same time, leisure increasingly unfolds indoors, framed by artificial lighting and climate control.

Brief walks outside do not always solve this. Clothing blocks sunlight, while winter limits ultraviolet exposure in northern regions. Sunscreen, essential for skin protection, further reduces vitamin D production. Consequently, insufficiency becomes widespread and often unnoticed. Blood calcium stays stable, but the body achieves this balance by drawing from bone reserves.

This quiet borrowing creates a slow deficit. Bones lose mineral content not because intake disappears entirely, but because absorption becomes inefficient. Over decades, this imbalance subtly reshapes skeletal architecture.

Dietary patterns add another layer to the story. Modern diets overflow with calories while undersupplying minerals. Ultra-processed foods dominate shelves and schedules because they are cheap, convenient, and engineered for craving. Unfortunately, they displace foods that naturally support bone health.

Calcium still appears on nutrition labels; however, it often arrives without its supporting cast. Magnesium, vitamin K, phosphorus, and trace minerals all matter for bone formation and maintenance. When diets skew heavily towards refined grains, sugars, and processed fats, this balance breaks down.

Salt deserves particular attention here. High sodium intake increases calcium loss through urine. Many processed foods contain far more salt than their flavour suggests. As a result, steady mineral leakage becomes normalised. Sugary drinks worsen the picture by replacing milk or mineral-rich alternatives while offering no skeletal benefit.

Protein often gets blamed unfairly. In reality, adequate protein supports bones by strengthening muscles and connective tissue. The problem arises when protein intake comes packaged with high sodium, low micronutrients, and minimal physical activity. In this context, imbalance rather than macronutrients alone shapes outcomes.

Longevity adds a revealing twist. People live longer than ever, which naturally increases fracture risk over time. Yet lifespan alone does not explain the modern osteoporosis epidemic. Earlier generations often remained physically active into old age out of necessity. Movement was embedded in daily survival rather than scheduled as exercise.

Today’s extended lifespan interacts with decades of low-impact living. Peak bone mass forms in early adulthood. From that point onward, maintenance becomes the goal. When young people spend formative years seated, indoors, and underloaded, their skeletal peak arrives lower than it should. Consequently, decline begins from a weaker starting point.

Hormonal changes accelerate this process. Menopause triggers rapid bone loss in women due to declining oestrogen levels. However, lifestyle strongly determines how much buffer exists beforehand. As a result, two women may experience the same hormonal shift while facing very different fracture risks.

Men are not immune either. Although male bone loss tends to progress more slowly, modern metabolic disease, inactivity, and low vitamin D levels erode that historical advantage. Over time, the gender gap in osteoporosis narrows as lifestyles converge.

What makes osteoporosis particularly unsettling is its invisibility. Bone loss produces no pain. Posture may change gradually, often attributed to ageing rather than structural weakness. Frequently, the first symptom appears as a fracture from an incident that feels trivial.

At that moment, the condition seems sudden. In reality, its roots stretch back decades. Osteoporosis is cumulative, reflecting long-term patterns rather than short-term mistakes.

Medical framing sometimes obscures this truth. Bone density scans, supplements, and medications play important roles, especially after diagnosis. Yet they arrive late in the story. No pill fully recreates bone that never formed or restores architecture lost to years of underuse.

Prevention, therefore, matters more than repair. Importantly, it does not require athletic extremes. Bones respond well to regular, varied loading. Walking, stair climbing, carrying groceries, resistance training, and balance-challenging activities all contribute meaningfully. When spread across the week, these signals accumulate.

Movement needs frequency more than intensity. Short bouts throughout the day often outperform isolated workouts. From the skeleton’s perspective, repetition matters more than motivation.

Sunlight remains biologically irreplaceable. Safe, regular exposure supports vitamin D synthesis in ways supplements cannot fully mimic. Where sunlight proves insufficient, supplementation helps; nevertheless, it works best alongside movement and adequate nutrition.

Dietary shifts matter too. Whole foods supply minerals in forms the body recognises. Dairy, leafy greens, nuts, seeds, fish with bones, and fermented foods all contribute differently. Consequently, variety reduces dependency on any single source.

Importantly, bone health intersects with balance and muscle strength. Many fractures occur not because bones weaken alone, but because falls become more likely. Therefore, strength, coordination, and confidence reduce fracture risk indirectly by preventing accidents.

Modern environments prioritise comfort. Chairs soften surfaces, shoes cushion impact, and floors smooth irregularities. While this comfort protects joints and reduces acute injury, it also deprives bones of challenge. Over time, the trade-off becomes costly.

Osteoporosis, then, is not simply a disease of ageing. Instead, it represents a structural response to how modern life organises bodies in space. It reflects the cumulative consequences of minimising friction, effort, and exposure.

Reframing bone health as a lifelong relationship rather than a medical condition changes priorities. The skeleton does not demand perfection. Rather, it asks for use. It expects gravity, resistance, and occasional discomfort. When those expectations go unmet, it adapts accordingly.

Seen through this lens, fragile bones are not mysterious. On the contrary, they are logical. They tell a story about how thoroughly modern routines have insulated humans from the forces that once shaped their bodies.

Osteoporosis becomes the skeleton’s quiet commentary on sedentary success. The challenge now lies in reintroducing just enough strain, sunlight, and nourishment to remind bones that they are still needed.