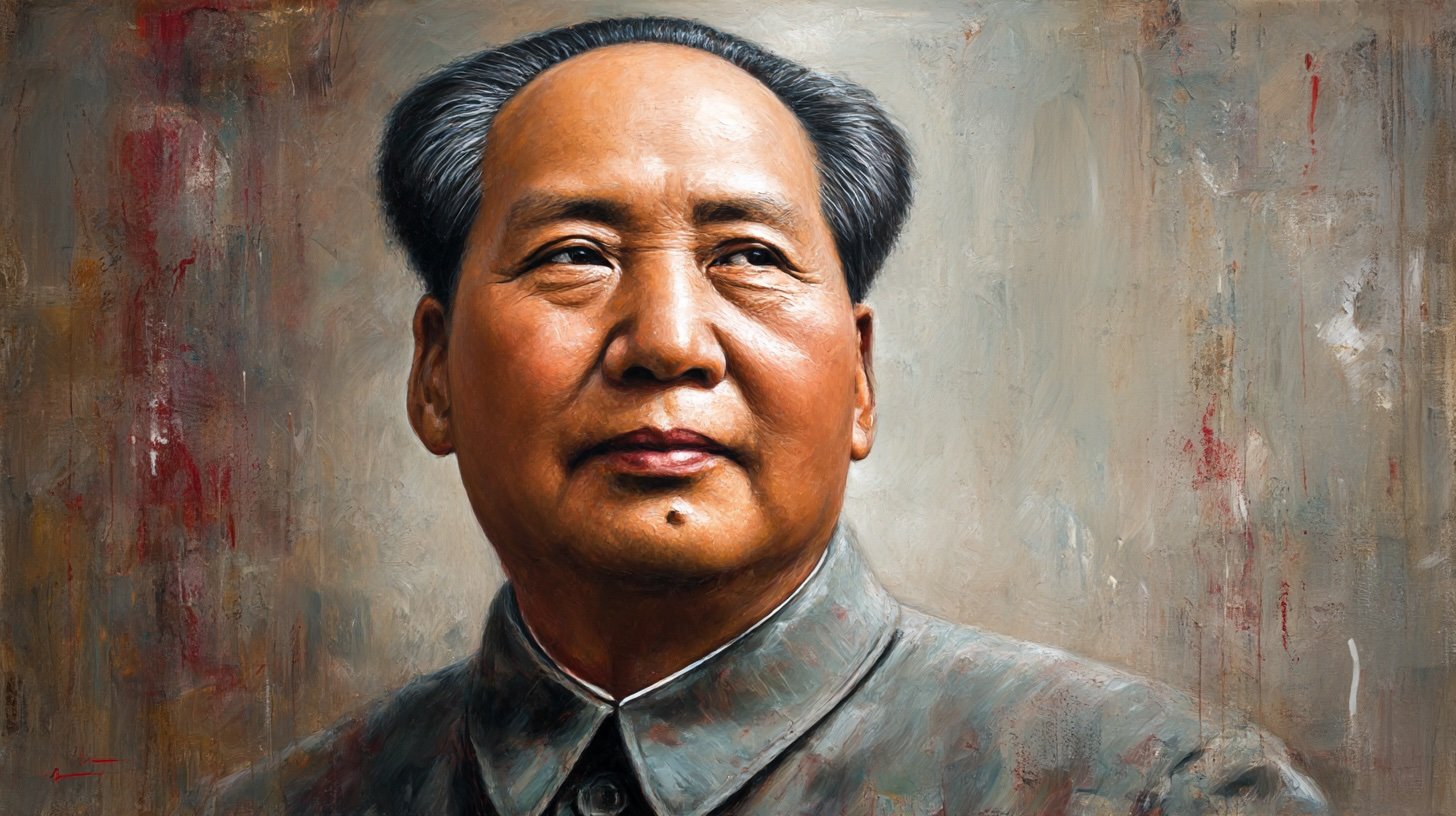

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong was not just a man. He was a paradox in motion, a walking contradiction who wore a poet’s robe over a general’s uniform, and somewhere underneath, stuffed a peasant’s heart. The name alone – Mao Zedong – still makes dinner parties in Beijing awkward and history classrooms in the West particularly tense. You either regard him as the father of modern China or the madman who orchestrated one of history’s most devastating social experiments. Sometimes both. And that, my friend, is where the fun starts.

Mao began life in the dusty village of Shaoshan, Hunan province, as the rebellious son of a wealthy farmer who didn’t particularly enjoy farming. Or fathers. As a teenager, he reportedly refused to wash his feet and slept on the floor because he thought beds were bourgeois. Later, he discovered communism, which allowed him to channel this adolescent defiance into a full-blown political ideology. In many ways, Mao turned Marx into a campfire story and China into the firewood.

He once declared that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” which might explain why he treated civil debate the way most people treat fruit flies. He launched the Chinese Civil War against the Kuomintang like a man who had skipped the seminar on compromise. And then came the Long March – 9,000 kilometres of pure chaos, death, and blisters. Only about a tenth of the 100,000 people who started it actually finished. Mao made it through with a bad back, a stronger grip on the Communist Party, and possibly the world’s most calloused feet.

He had a knack for theatrical politics. When he proclaimed the People’s Republic of China in 1949 from atop Tiananmen Gate, it wasn’t just a victory lap. It was Act I of a drama that would rewrite everything. Land reform came first. Wealthy landlords were humiliated and executed in village squares while peasants cheered and sometimes pointed fingers with suspicious enthusiasm. Then came collectivisation, which sounded noble and ended up feeding propaganda more than people.

The Great Leap Forward was neither great nor forward. Picture a nation melting down its cooking pots to build backyard steel furnaces, only to end up with metal that could barely hold a soup, let alone an economy. Tens of millions died in the resulting famine, but official records usually cite a lot of euphemisms like “difficulties” and “weather-related issues.” Mao blamed the sparrows, literally. He believed birds were eating too much grain, so he declared a war on them. Peasants were ordered to clap and shout until the birds dropped dead from exhaustion. The unintended consequence? Insects ran riot and the crops fared even worse.

Mao also fancied himself a poet and swimmer. His poems were full of violent metaphors and his swimming stunts became legendary. He once staged a televised swim across the Yangtze River to show he was in excellent health, despite being in his seventies and rumoured to be a bit more corpse than comrade by that point. Doctors may have rolled their eyes, but the cameras rolled anyway.

Then came the Cultural Revolution. If the Great Leap was a punch in the gut, the Cultural Revolution was a long, slow, chaotic headbutt. Students formed Red Guard units, denounced their teachers, burned books, and vandalised temples in what essentially became a nationwide puberty tantrum with state backing. Mao, ever theatrical, reappeared on a balcony now and then waving his Little Red Book, the most dangerous self-help manual ever published.

His personality cult reached such surreal heights that peasants carried his portrait into the fields like a scarecrow blessed by Marx himself. Factories held Mao Thought study sessions instead of safety drills. A single offhand comment by Mao could reroute an entire industrial policy. He wielded ideology like a sledgehammer, and often as precisely.

Yet amid the ruin, Mao remained something of a mystical figure. He hardly bathed, preferred young nurses around him at all times (for “vital energy,” according to his personal physician), and sometimes stayed up all night reading history books or plotting political purges. People whispered that he rarely brushed his teeth, believing tea rinses were sufficient. This from the man who rewrote China. Halitosis and all.

He read extensively, but selectively. Romance of the Three Kingdoms was his favourite, a classic of war, betrayal, and grand strategy. It’s not hard to see why. He practically treated life like a chapter from it, with dramatic alliances, cunning backstabs, and glorious battles won on both the field and the page.

Oddly, Mao’s economic instincts were a bit less literary. He once predicted that China would surpass Britain’s steel output in a matter of years, mostly by getting farmers to smelt scrap metal in their courtyards. Spoiler alert: it did not. The metal was useless, and the farms were empty.

He distrusted intellectuals, unless they wrote flattering essays about him. Scientists, economists, professors – all were suspect unless they knew how to recite party slogans with the vigour of a cheerleading squad. Universities became battlegrounds. Libraries turned into bonfires.

Foreigners fascinated him, especially Richard Nixon. Mao, half-dead and propped up with pillows, met Nixon in 1972 in what looked like a fever dream of geopolitical theatre. The handshake between the old revolutionary and the Cold War capitalist is still one of the most awkward yet symbolic gestures ever caught on film. Mao joked he couldn’t really talk politics anymore and left most of the work to Zhou Enlai, who probably wished he’d brought a stronger cup of tea.

Despite all the turbulence, the man could command a room. Or a nation. He turned the calendar, scrubbed traditions, and redesigned Chinese society on a whim. He renamed months, rewrote textbooks, and occasionally changed his mind just to keep everyone guessing. It wasn’t leadership so much as improv theatre with disastrous real-world consequences.

He adored peasant imagery. Posed with bundles of wheat, wore the classic tunic that became known as the Mao suit, and immortalised the countryside while barely setting foot in a rice paddy after the revolution. Like many ideologues, he romanticised the poor while avoiding their lifestyle. Revolution, it turned out, is more comfortable when conducted from a villa.

Mao also dabbled in matchmaking. During the Cultural Revolution, he personally intervened in marriage proposals among his inner circle. Love, apparently, was also subject to the whims of dialectical materialism.

He wrote the party’s anthem, redesigned its rituals, and basically moonlighted as both president and performance artist. His handwriting was turned into typeface. His quotes became slogans, then commandments, then excuses. Entire factories shut down to study his thoughts. People studied Mao the way medieval monks studied scripture: obsessively, symbolically, and occasionally with a side of persecution.

By the time he died in 1976, he had outlived most of his enemies and allies, buried millions of citizens under his plans, and created a political structure that would outlast even his embalmed body. Speaking of which – yes, he’s still on display in Beijing. Looking vaguely waxy and eternally unimpressed.

China today is a strange inheritance of his legacy: capitalist hustle under a red flag. A place where billionaires quote Mao unironically, and party officials still perform ideological rituals before opening billion-dollar tech parks. He remains both taboo and sacred, criticised in whispers and worshipped in murals.

So there he is: the man who taught a billion people to think in slogans, act in waves, and cheer for things they didn’t quite understand. Mao Zedong wasn’t just a leader. He was a historical event in trousers. And like all big events, he left a mess behind for others to sort out.

And if history has taught us anything, it’s that messes make the best stories.