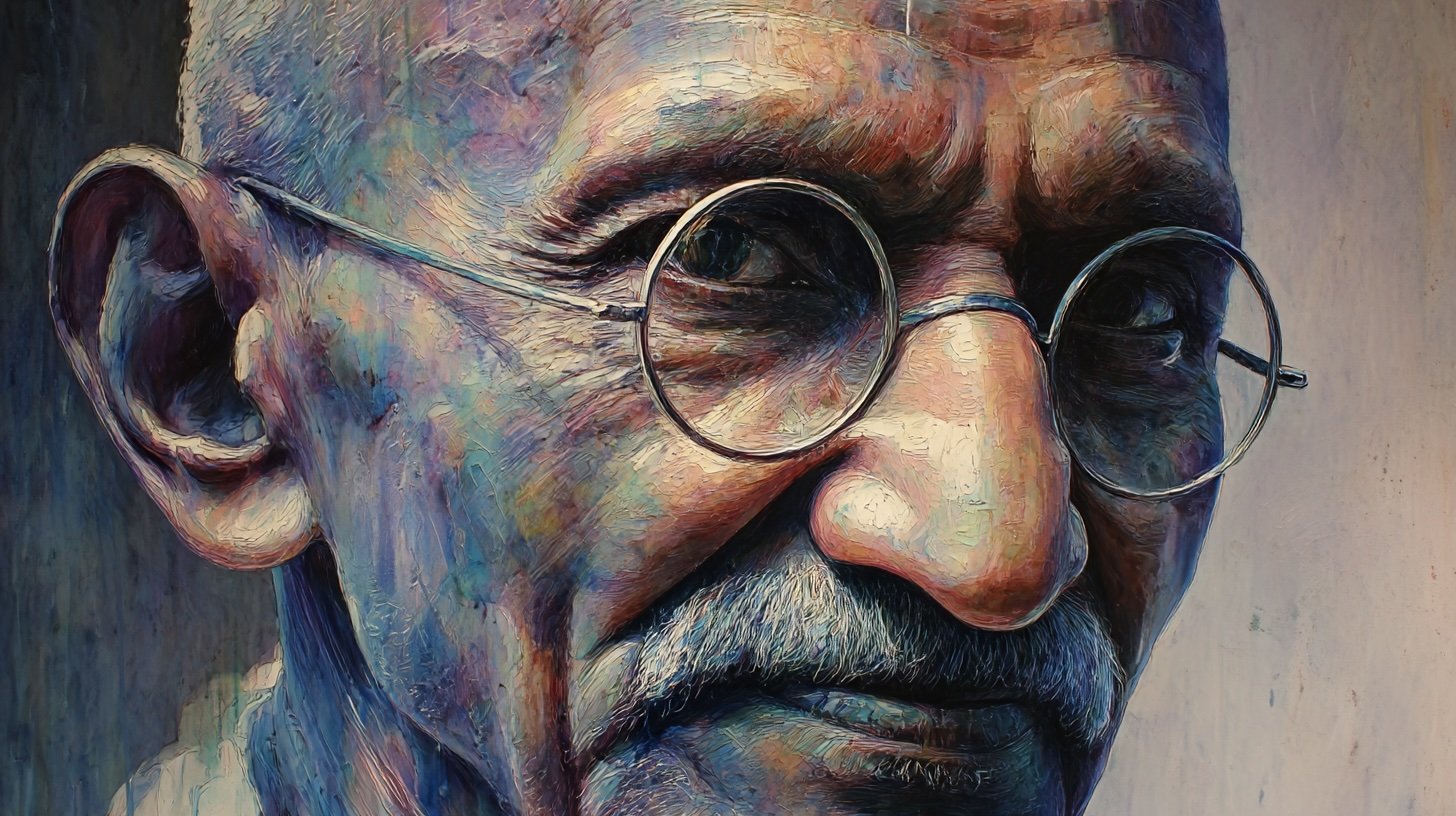

How Mahatma Gandhi Broke the Salt Law

Mahatma Gandhi isn’t just a name in a history textbook or a solemn statue staring into the middle distance in some government garden. He was many things: lawyer, philosopher, political wizard, dietary extremist, and yes, someone who really did spin his own clothes with the kind of dedication most people reserve for Netflix.

Before becoming the poster-child for peaceful protest, Gandhi got kicked out of a first-class train compartment in South Africa. That moment, freezing on a platform in Pietermaritzburg, didn’t just ruin his travel plans. It flipped a switch. He went from barrister in fancy British suits to the guy who made global empires sweat with nothing but homespun cloth and stubbornness.

He wasn’t born “Mahatma”. The name means “great soul” and, to be clear, he didn’t give it to himself. That would have been weird. A poet and philosopher, Rabindranath Tagore, pinned that one on him. Gandhi himself would’ve preferred something more modest—possibly “guy who really, really hates salt taxes.”

Speaking of salt, let’s talk about that one time he walked 240 miles just to break a law about seasoning. The Salt March of 1930 wasn’t just a long hike. It was a masterclass in absurd yet powerful protest. The British taxed salt, so Gandhi did what any strategic minimalist would do: walked for weeks, gathered some salt from the seashore, and made headlines around the world. Not bad for beachcombing.

His legal career started in London, where he was famously awkward. Think: painfully shy vegetarian who avoided eye contact and tried ballroom dancing (once). He also tried to brush up on his manners with a guidebook called “Advice to a Lady,” apparently misled by the title.

Gandhi was a staunch advocate for nonviolence, but his kids might describe him as a bit of a strict dad. He demanded celibacy from his followers and tried to enforce it in his own household—even on his wife. That bit didn’t go over well. Kasturba Gandhi, a political force herself, told him off on more than one occasion. The myth of serene domestic life? Not so serene.

He also wasn’t above experimenting on himself. Gandhi dabbled in all sorts of dietary extremes: no meat, then no dairy, then no spices, then no cooked food, then no food at all. He treated his stomach like a laboratory and once declared that boiled water was a form of sin. British rule was not the only thing he tried to purge.

For someone who wore barely more than a dhoti, Gandhi had an outsized influence on fashion. His spinning wheel became a symbol of resistance. He insisted Indians boycott British textiles and spin their own cloth. It wasn’t just economic—it was deeply personal. Also, it made for some fairly drafty attire.

Time magazine named Mahatma Gandhi the Man of the Year in 1930, but he never won the Nobel Peace Prize. Nominated five times, always admired, but never awarded. The Nobel Committee later admitted that skipping him was kind of a miss. Too late, chaps.

Einstein, not exactly known for florid praise, said, “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.” Gandhi wasn’t moved. He didn’t care much for compliments, or shoes.

He wrote letters to everyone. Like, everyone. Hitler got one, asking him to stop the whole war thing. Roosevelt got one too, complete with a request for spinning wheels. Tolstoy and Gandhi had a pen-pal bromance. If Gandhi had lived today, he’d probably have a Substack.

His weapon of choice? A hunger strike. Gandhi went on 17 fasts during India’s struggle for independence. Some lasted over three weeks. He used his body like a moral megaphone, turning guilt into a political instrument. It wasn’t emotional blackmail; it was spiritual warfare.

Despite the global attention, Gandhi was never part of India’s first independent government. He didn’t want power. He wanted results. And spinning. Lots of spinning.

He was arrested multiple times by the British, but he had a knack for turning prison into a productivity zone. While incarcerated, he wrote, read, fasted, and dictated political manifestos. Jail was just another office space, really.

His assassin, Nathuram Godse, was a Hindu nationalist who claimed Gandhi was too soft on Muslims. That Gandhi was killed by a fellow Hindu is still one of the many bitter ironies of history. His final words, reportedly, were “Hey Ram”.

Mahatma Gandhi was obsessed with self-control. He kept detailed records of his bodily functions, including a logbook of bowel movements. He believed in knowing thyself to an awkward degree.

He also believed in living simply. His possessions at the time of death? A watch, spectacles, sandals, eating bowl, and a spinning wheel. And yet this minimalist managed to undo the most powerful empire on earth.

He held court with kings and beggars alike. British Viceroys and London elites often found him baffling. Here was a man who showed up for state dinners barefoot, sat cross-legged, and argued in parables.

Churchill once described him as a “half-naked fakir”. Gandhi replied with silence. And more salt.

He campaigned not just for Indian independence but also for the uplift of the so-called “untouchables,” whom he renamed “Harijans,” or “children of God.” For this, he took plenty of heat from orthodox Hindus.

His personal doctor was often worried about Gandhi’s health. But Gandhi ignored him in favour of goat’s milk, sunlight, and fasting. He distrusted modern medicine and thought illness was often moral or spiritual.

His moral experiments often bordered on the unsettling. Late in life, he shared beds with young women to “test” his celibacy. Even his most devoted followers squirmed. Gandhi wasn’t a saint. He was a complicated human with contradictions galore.

His face now graces Indian rupee notes. He’d probably hate that. Gandhi wasn’t a fan of wealth, banks, or anything resembling capitalism. If he could choose, he might put a spinning wheel there instead.

He loved walking. Whether it was the Salt March or his daily rounds, Gandhi was a relentless pedestrian. Cars were too fancy, trains too fast. He preferred bare feet and dust.

He was assassinated on January 30, 1948, just months after India’s independence. The man who preached peace met a violent end. That contradiction didn’t erase his legacy—if anything, it underlined it.

And finally, Gandhi once said, “You may never know what results come of your actions. But if you do nothing, there will be no result.” Turns out, spinning wheels and moral clarity make for a surprisingly effective revolution.