Lewis Carroll: When Nonsense Makes Perfect Sense

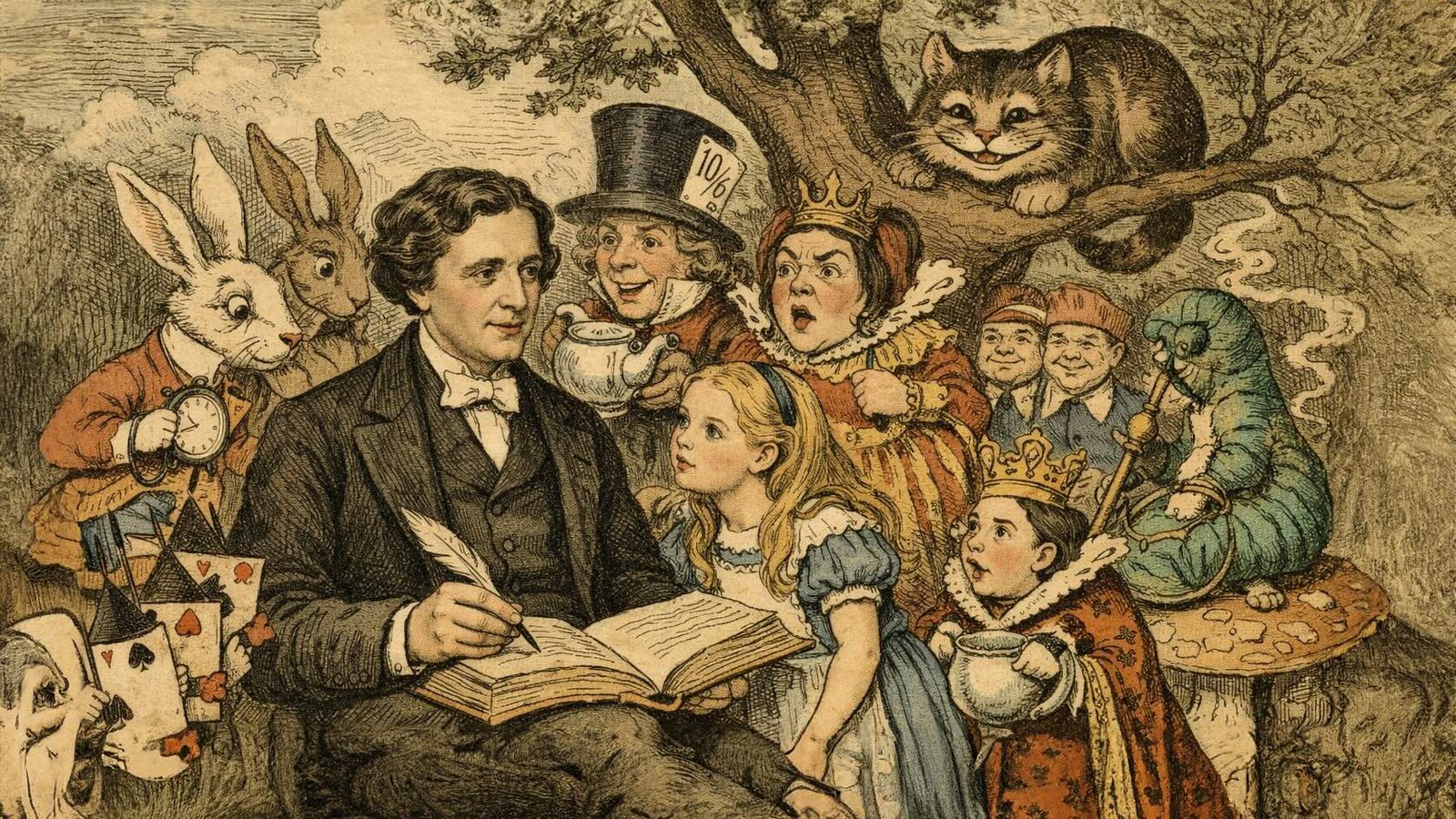

Picture a Victorian mathematician sitting in his Christ Church chambers at Oxford, carefully constructing sentences that make absolutely no sense whatsoever. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson spent his daylight hours teaching geometry and determinants to undergraduates. They found his lectures “singularly dry and perfunctory.” Yet when evening fell, he transformed into Lewis Carroll. This man understood that the surest path to wisdom might just be paving it with utter gibberish.

Carroll’s nonsense wasn’t the careless kind. Moreover, it operated on its own peculiar logic—a system so rigorous that mathematicians still puzzle over it today. When he wrote “Twas brillig, and the slithy toves / Did gyre and gimble in the wabe,” he wasn’t simply stringing together random syllables. Instead, he was conducting an experiment. Could meaning emerge from words that technically meant nothing at all?

The portmanteau became Carroll’s signature invention. He didn’t invent the suitcase-style luggage the word originally described. What he did create was a linguistic phenomenon that packed two meanings into one delicious syllable cluster. “Slithy” meant lithe and slimy. Similarly, “mimsy” combined flimsy and miserable. In Through the Looking-Glass, Humpty Dumpty explained it to Alice: “You see it’s like a portmanteau—there are two meanings packed up into one word.” This wasn’t wordplay for its own sake. Rather, it demonstrated something profound about how language actually works. Our brains can extract sense from partial information, constructing meaning from context clues and sound associations.

Carroll gave us “chortle” (chuckle plus snort). It has become so embedded in English that most people don’t realise they’re speaking Carrollian when they use it. Likewise, “galumph” entered the lexicon. Originally it meant to move with galloping triumph, though modern usage has stripped away the victory. We’re left with clumsy lumbering. These words succeeded because they felt right, even when they were entirely made up. Linguists call this open-endedness or productivity—the human capacity to endlessly generate new meanings. Indeed, Carroll simply weaponised it for entertainment.

But Carroll’s real genius lay in how his nonsense functioned as a precision instrument. As a mathematics lecturer at Oxford, he wasn’t a particularly distinguished researcher. Nevertheless, he possessed an obsessive interest in logic that manifested in everything he touched. His nonsense poems and stories operated like logical proofs turned inside out. Consider Alice’s famous arithmetic confusion: “Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven—oh dear!” She continues: “I shall never get to twenty at that rate!” This sounds like pure confusion. Yet it follows a precise mathematical pattern involving progression through different number bases. In base-18, four times five genuinely equals twelve. Therefore, Carroll wasn’t being random. He was satirising contemporary developments in mathematics that he found troubling.

Victorian mathematics was experiencing a revolution that made the conservative Carroll deeply uncomfortable. Symbolic algebra was divorcing mathematics from concrete numbers. It treated symbols as entities in themselves. Meanwhile, William Rowan Hamilton had introduced quaternions—a coordinate system based on four terms including time. They could describe three-dimensional rotation. Carroll loathed these abstractions. Consequently, he encoded his objections into Alice in Wonderland. He transformed complex mathematical critiques into children’s entertainment.

The Mad Tea Party becomes deliciously subversive when you understand its target. Three characters circle endlessly around a table in perpetual teatime. The fourth member—Time himself—remains conspicuously absent. This wasn’t random whimsy. Rather, it mocked Hamilton’s quaternions, which required that fourth dimension to function properly. Without time, the remaining three dimensions could only rotate in a flat plane. They go round and round like hands on a clock. Essentially, Carroll trapped Hamilton’s characters in mathematical purgatory. They’re unable to escape their circular motion because he’d removed their fourth dimension. The Mad Hatter’s obsession with time—”if you knew Time as well as I do”—suddenly reads differently. It’s less like charming nonsense and more like pointed academic satire.

Carroll wielded logic puzzles like a surgeon wields a scalpel. Furthermore, he created hundreds of them. They trained readers in systematic reasoning through deliberately absurd premises. “All babies are illogical,” one puzzle begins. “Nobody is despised who can manage a crocodile. Illogical persons are despised.” Therefore, babies cannot manage crocodiles. The conclusion follows impeccably from ridiculous premises—precisely Carroll’s point. After all, logic doesn’t care whether your starting assumptions make sense. It simply cares whether your reasoning process holds together.

His logic work reached its apex in “What the Tortoise Said to Achilles.” It was published in the philosophical journal Mind in 1895. This deceptively simple dialogue revealed a fundamental problem in logical reasoning. It still lacks a universally accepted resolution. The Tortoise traps Achilles in an infinite regress. He constantly demands one more premise before accepting a conclusion. Each time Achilles adds another logical step, the Tortoise requests yet another step to justify that justification. This paradox, sometimes called Carroll’s paradox of inference, demonstrated something crucial. You can’t reduce logic entirely to rules without ending up in philosophical quicksand. Modern formal logic largely sidesteps this problem by treating inference rules as part of the system itself. Nevertheless, Carroll’s playful dialogue continues to provoke serious philosophical debate.

Carroll also invented the word ladder, which he called “doublets,” during Christmas 1877. Players transform one word into another by changing a single letter at each step. CAT becomes COT becomes DOG. Simple enough, except Carroll typically chose word pairs with semantic relationships. He’d turn BLACK into WHITE, evolve APE into MAN, or make FLOUR into BREAD. These puzzles became an instant sensation when they appeared in Vanity Fair in 1879. Subsequently, Macmillan published collected editions that sold out repeatedly. The game demonstrated Carroll’s belief that mental exercise should be rigorous yet delightful, challenging yet accessible.

His “Jabberwocky” became nonsense literature’s crowning achievement. The poem was so influential that it spawned an entirely new word. “Jabberwocky” itself now means meaningless speech. Carroll later explained that the title combined “jabber” with the Anglo-Saxon “wocer,” meaning offspring or fruit. This made it “the result of much excited discussion.” The poem’s genius lies in how it conveys a complete heroic narrative whilst using largely invented vocabulary. Readers instantly grasp that someone slays something dangerous and returns home triumphant. This happens despite encountering words like “frabjous,” “vorpal,” and “uffish” for the first time. Clearly, context and syntax carry meaning even when individual words don’t.

Douglas Adams paid homage to this technique in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. His Vogon poetry reads: “Oh freddled gruntbuggly thy micturations are to me / As plurdled gabbleblotchits on a lurgid bee.” The tradition continues—using Carroll’s framework whilst inserting different nonsense words. Moreover, “Jabberwocky” has been translated into sixty-five languages. Translators create equivalent portmanteaus that capture the poem’s spirit whilst respecting their language’s morphology. This proves that Carroll’s innovation transcended English itself. He’d discovered something fundamental about how humans process language.

The photograph of young Alice Liddell in a tattered dress haunts Carroll scholarship. It’s part of his extensive photographic portfolio. That portfolio included around thirty nude or semi-nude studies of children. Victorian attitudes toward childhood and innocence differed dramatically from modern sensibilities. Yet these images remain deeply uncomfortable. Furthermore, Carroll’s family destroyed pages from his diary after his death. This included entries from June 1863 when his relationship with the Liddell family abruptly ended. Speculation has swirled for over a century about what caused the break. Some suggest he proposed to eleven-year-old Alice, though no evidence supports this. Others point to gossip about the family’s governess or Alice’s older sister Lorina.

Scholar Karoline Leach challenged what she termed “the Carroll Myth.” She questioned the image of Carroll as an unworldly figure obsessed exclusively with prepubescent girls. Her research revealed that Carroll maintained numerous friendships with adult women. Many of his so-called “child-friends” were actually in their late teens or twenties. She argues that his family’s post-mortem suppression of evidence about his adult relationships created a false narrative. Combined with Victorian sentimentality about childhood innocence, it led subsequent biographers to perpetuate rather than question this myth. Nevertheless, the uncomfortable questions persist, complicated by Victorian social norms that seem alien to modern readers.

Absurd conspiracy theories have attached themselves to Carroll over the years. Richard Wallace published books claiming that anagrams hidden in Carroll’s works proved he was Jack the Ripper. These theories were so thoroughly debunked that they’ve become cautionary tales about overzealous pattern-finding. Similarly, the idea that Carroll wrote Alice whilst under the influence of opium or laudanum emerged during the 1960s counterculture movement. There’s zero evidence for this claim and considerable evidence to the contrary. The story came from a rowing trip in 1862 where Carroll entertained the Liddell sisters with an improvised tale.

What remains undeniable is how Carroll’s mathematical mind shaped his literary output. When Alice encounters the Cheshire Cat and later Humpty Dumpty, she’s engaging with characters who embody logical paradoxes. The Cat can disappear leaving only its grin. In Carroll’s universe, properties can exist independently of their subjects—a concept that troubled him in abstract algebra. Meanwhile, Humpty Dumpty insists that words mean exactly what he chooses them to mean, no more and no less. This raises genuine questions about linguistic authority that philosophers still debate.

Carroll’s work on voting theory and committee procedures demonstrated that his logical interests extended beyond pure mathematics. They reached into practical applications. He developed what’s now called Dodgson’s method for determining election winners. This anticipated modern concerns about voting systems by decades. His symbolic logic textbooks were dismissed during his lifetime as frivolous because they appeared under his pseudonym. Yet they anticipated developments in formal logic that wouldn’t emerge until well into the twentieth century. Notably, Martin Gardner’s rediscovery of Carroll’s logical work in the 1960s sparked renewed academic interest. People became fascinated with Dodgson the mathematician, not just Carroll the storyteller.

The tension between Dodgson and Carroll formed the creative engine of his career. Dodgson the mathematician lived methodically. He documented over 98,000 letters in a special register he devised, teaching classes, attending Christ Church chapel. In contrast, Carroll the author explored Wonderland, where logic bends back on itself, where babies turn into pigs, where time can be murdered. This wasn’t split personality but rather productive dialogue—the rigorous thinker using fantasy to interrogate reality.

Carroll understood that systems can be simultaneously rigorous and absurd. His logic puzzles proved that conclusions could be perfectly valid whilst being obviously untrue. Additionally, his portmanteau words demonstrated that meaning emerges from structure as much as definition. His mathematical satires showed something important. Taking abstract concepts to their logical conclusion often reveals their absurdity. Thus, nonsense, in Carroll’s hands, became the most serious game imaginable. It was a systematic exploration of where meaning lives, how language works, and what happens when you push logical systems to their breaking points.

Contemporary mathematicians still discover new applications for Carroll’s work. His condensation method for evaluating determinants led to the alternating sign matrix conjecture. It’s now proven as a theorem. His ciphers employed sophisticated mathematical concepts decades ahead of their time. Furthermore, game theorists study his puzzle structures. Linguists analyse his portmanteau constructions. He occupies a unique position—a Victorian don whose children’s stories contain doctoral-level insights into formal systems.

Perhaps Carroll’s greatest trick was making profundity feel like play. Children read Alice and laugh at talking animals. Adults read Alice and recognise satires of mathematical developments, philosophical puzzles about identity and language, logical paradoxes wrapped in whimsy. Both readings are equally valid because Carroll built multiple meanings into his nonsense. He created stories that genuinely work on different levels simultaneously. They don’t simply include references that sail over children’s heads.

The pleasure of Carroll’s nonsense comes from that delicious moment when the absurd suddenly makes perfect sense. You realise that “mimsy” absolutely must mean flimsy and miserable because nothing else would sound quite right. The Mad Tea Party’s circular motion satirises mathematical theory. And “What the Tortoise Said to Achilles” asks a question about logical inference. Professional philosophers still can’t answer it. Indeed, nonsense becomes a tool for revealing how much structure underlies meaning. Systems that seem solid can collapse into infinite regress. Words we think we understand might mean something entirely different.

Carroll spent his career proving several things. You don’t need sense to have meaning. Rigorous logic and utter absurdity can coexist. The most profound insights sometimes come wrapped in silliness. His portmanteau words, impossible creatures, and twisted logic continue demonstrating something fascinating. The systems we use to make sense of the world—mathematics, language, logic—are themselves rather wonderfully mad. We’ve simply agreed to pretend they make sense. It’s precisely the way we agree that “slithy” sounds exactly like something that would be both lithe and slimy. Ultimately, Carroll knew that nonsense isn’t the opposite of sense. Instead, it’s sense’s strange and necessary twin. It’s the place where meaning goes to test its boundaries and occasionally discover that those boundaries were always more flexible than anyone imagined.