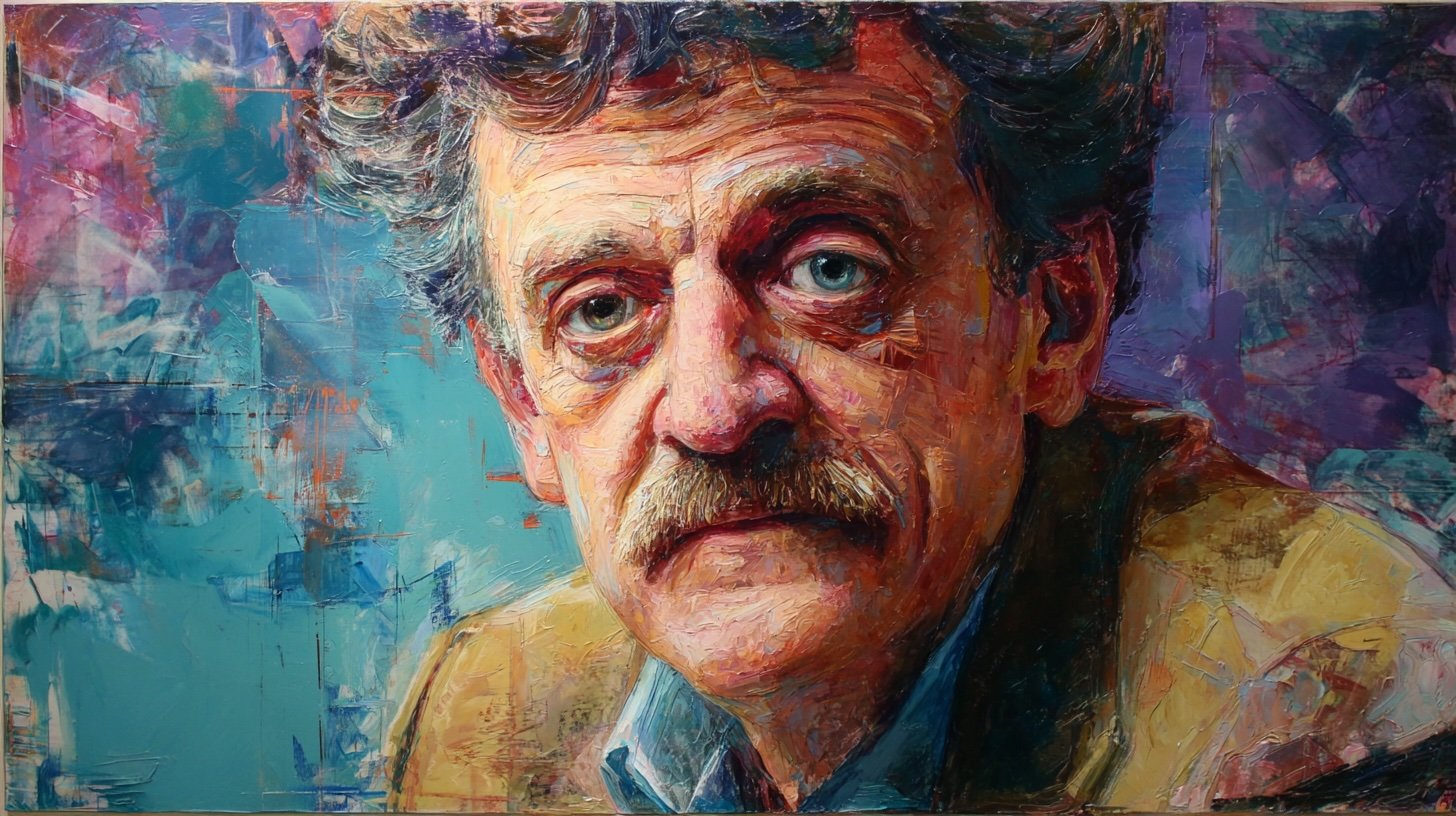

The Humanism, Irony and Apocalypse of Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut was that rare writer who managed to be both a pessimist and a moral optimist, a man who saw humanity as doomed yet refused to stop caring. His life was as much a study in contradiction as his novels, and perhaps that’s what makes him so enduring. Born in Indianapolis in 1922, he came from a well-off German-American family that lost its footing in the Great Depression. His father’s architecture practice collapsed, his mother slipped into depression, and Vonnegut watched the American dream unravel before he even understood what it was meant to be.

When war came, he signed up like so many young men of his generation, though his experience turned out far from heroic. Captured during the Battle of the Bulge, he was locked up in a German slaughterhouse in Dresden. There, amid the smell of livestock and death, he survived the Allied firebombing that levelled the city in February 1945. It’s the kind of trauma that either breaks you or makes you write Slaughterhouse-Five — Vonnegut’s great anti-war masterpiece that would later turn him into a reluctant literary celebrity.

After the war, he went back to the United States, studied anthropology, worked as a journalist and publicist, and began writing fiction that no one initially wanted. His first novel, Player Piano, appeared in 1952 — a bleakly funny take on automation and alienation. The book imagined a world where machines had taken over human jobs, leaving people with nothing to do but pretend their lives still mattered. Sound familiar? Decades later, his warnings about dehumanising technology read like prophecy. Silicon Valley just didn’t get the joke.

Vonnegut’s writing style was deceptively simple: short sentences, conversational tone, a refusal to take himself too seriously. He’d tell cosmic jokes, then remind you that the punchline was humanity itself. His recurring phrase, “And so it goes,” became the anthem for fatalism wrapped in absurd humour. He’d mix time travel, aliens, and bureaucracy into the same paragraph and make it feel perfectly reasonable. He was a science-fiction writer who refused to be called one, a satirist who seemed deadly serious about kindness.

In Cat’s Cradle (1963), Vonnegut introduced ice-nine, a substance capable of freezing the world solid. It was a dark parable about scientific irresponsibility, religion as theatre, and the human craving for meaning. He made apocalypse feel almost domestic, like something you might trip over on the way to the kitchen. The Sirens of Titan, Breakfast of Champions, and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater all followed this same pattern: funny until they weren’t, absurd until they cut deep.

But behind that sardonic grin lay plenty of turmoil. Vonnegut’s personal life wasn’t the calm, wise-novelist story people liked to imagine. He could be charming and infuriating in the same breath. Biographers described him as volatile, resentful, even cruel to those closest to him. He struggled with depression, divorce, and a lifelong sense that fame had come too late and at too high a cost. The grandfatherly figure with the unkempt hair and wry smile hid a much darker, more cynical man who never stopped being haunted by Dresden.

Controversy clung to him, though not always for the reasons he expected. His short story Welcome to the Monkey House drew criticism for its troubling sexual politics — a plot involving a man who rapes a woman to “liberate” her from numbness. What once passed as edgy satire now reads uncomfortably tone-deaf. Critics have also long debated whether his signature fatalism was moral cowardice or existential realism. Was “so it goes” a shrug or a prayer?

Then there were the factual disputes. Slaughterhouse-Five’s Dresden death toll has been challenged by historians, and Vonnegut’s blend of memoir and invention muddied the line between witness and storyteller. Yet his book remains one of the most powerful anti-war works ever written precisely because it refuses to moralise. He didn’t lecture; he laughed — and in doing so, made horror bearable.

Vonnegut’s politics were equally divisive. He was an unapologetic liberal who railed against greed, bureaucracy, and war. Some admired his bluntness; others dismissed him as preachy. But even his harshest critics couldn’t deny that he was right about more things than most politicians. His dystopias were never about the future; they were autopsies of the present.

He also courted the kind of controversy that comes with being canonised. His works were banned and challenged in American schools for decades, often lumped in with the supposed moral decay of modern literature. Parents didn’t appreciate his casual blasphemy or bleak humour. Teenagers, naturally, adored him for exactly those reasons. To be caught reading Slaughterhouse-Five in class was almost a rite of passage.

What made Vonnegut special wasn’t just his ability to predict society’s absurdities but to wrap them in warmth. For all his cynicism, he insisted on kindness as the last sane act in a senseless world. “If this isn’t nice, what is?” he used to say — a line that could’ve come from your favourite uncle if your favourite uncle also believed civilisation was a cruel joke.

And he never lost his edge. Even late in life, he took aim at everything from corporate greed to George W. Bush. His essays in A Man Without a Country (2005) read like dispatches from an old soldier of sanity watching the empire crumble. He was funny to the end, even when he didn’t mean to be. When asked what should replace religion, he quipped, “The Sermon on the Mount.” That was Vonnegut in one sentence — sarcastic, humane, and utterly unimpressed by human pretension.

His legacy is tangled, as legacies tend to be. He was a feminist hero to some, a misogynist to others. A humanist moralist to his fans, a grumpy contrarian to his peers. He didn’t belong neatly anywhere, which might explain his lasting relevance. In an era of algorithmic outrage and curated identities, Vonnegut’s messy, contradictory humanity feels refreshing. He admitted he didn’t have the answers. He just wrote as if honesty — even dark, bitter honesty — might be the closest thing we had to grace.

Maybe that’s why, decades after Slaughterhouse-Five, people still quote him, teach him, argue about him. He made literature that didn’t flinch, that refused to separate tragedy from farce. He turned trauma into satire and despair into a punchline you couldn’t quite laugh at. For a man who doubted almost everything, he gave readers a strange kind of faith — not in God or progress, but in the fragile, ridiculous miracle of being human. And so it goes.