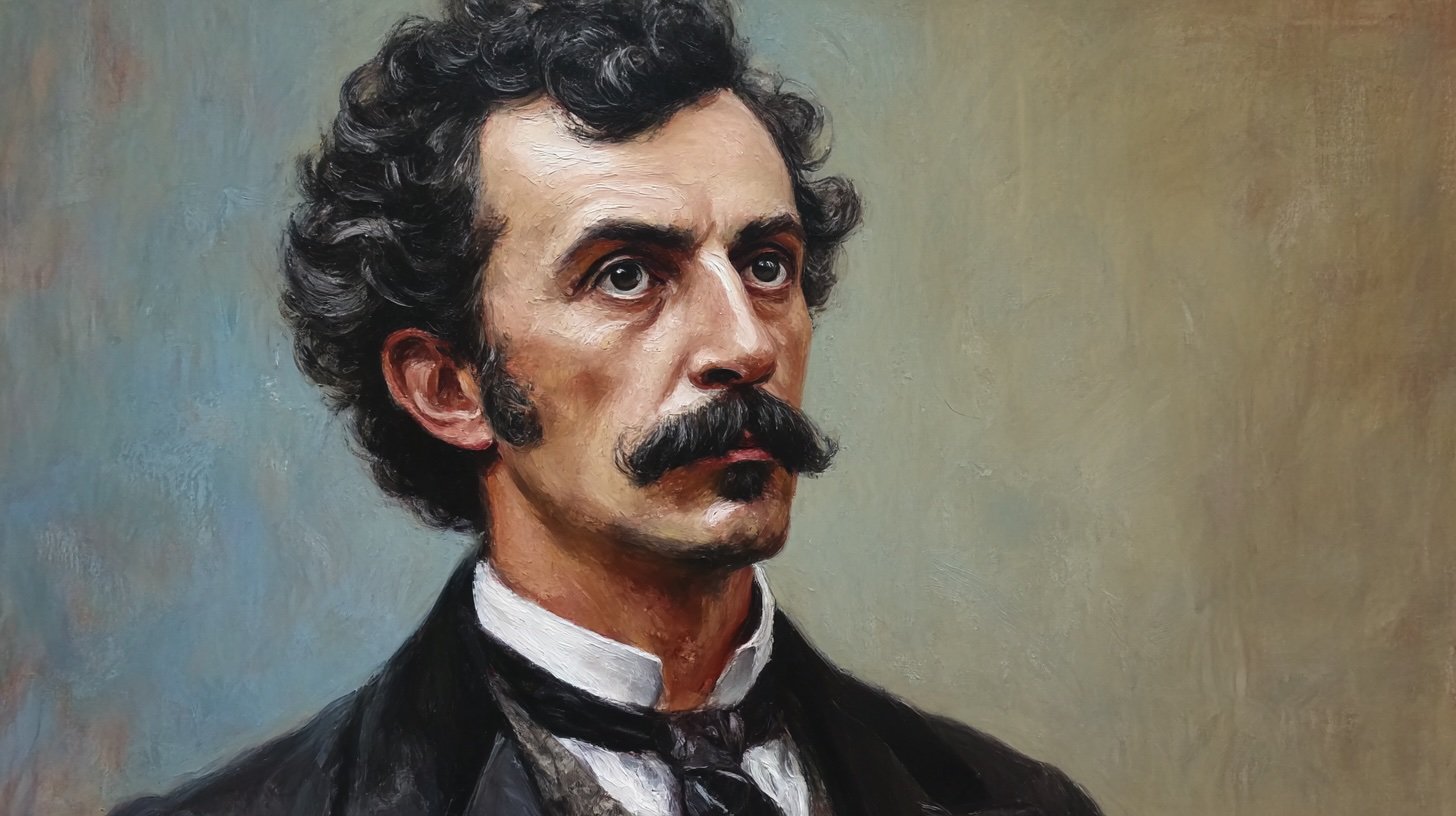

John Wilkes Booth: Drama Turned Tragedy

If history were a theatre production, John Wilkes Booth would be that overly dramatic understudy who not only hijacks the final act but sets the stage on fire, delivers a monologue in blood-soaked velvet, and flees into the night convinced he’s just won a Tony. It all started with a bullet, a balcony, and an actor who took his role a bit too seriously. The story of Booth isn’t just about a man who assassinated Abraham Lincoln; it’s about a Southern heartthrob turned extremist who believed he was making history, only to end up as a tragic footnote with delusions of grandeur and a fatal flair for melodrama.

Booth was born in 1838 in Bel Air, Maryland, which despite its charming name and proximity to the Mason-Dixon Line, clung to its Southern loyalties like a damp Confederate flag. His father, Junius Brutus Booth (yes, that was his actual name, and yes, it’s as dramatic as it sounds), was a Shakespearean actor who specialised in intense performances and erratic behaviour—a real method actor before method acting had a name. The Booth household practically reeked of greasepaint, ego, and impromptu Hamlet soliloquies.

John, inevitably, took to the stage like a duck to a fog machine. By his twenties, he was already a matinee idol, a dashing presence in theatres from Boston to New Orleans, with a jawline that could cut glass and a voice that made genteel ladies swoon. He was famous, adored, and had the kind of devoted fanbase that would make modern influencers jealous. But, as it often happens with men who receive too much applause too early, Booth wanted more than roses at curtain call. He wanted to be remembered. And not just remembered—lionised.

Trouble was, Booth’s ambitions veered away from the dramatic arts and straight into political fanaticism. And by convictions, we don’t mean the sort that earn you a medal or a bust in a town square. We mean an all-consuming hatred for Abraham Lincoln, the Union, and most alarmingly, the idea that Black Americans might be treated as equals. Booth was a Confederate sympathiser through and through, even though he never wore the uniform or fired a musket in battle. He preferred to wage war from the comfort of theatre dressing rooms and smoky parlour discussions with other armchair generals.

He believed Lincoln was a tyrant, a Caesar ripe for assassination. In Booth’s twisted mind, he was Brutus, destined to save the Republic—although his understanding of Shakespearean irony was, shall we say, limited. Surrounded by a motley crew of Confederate dreamers, disgruntled civilians, and aspiring conspirators with more passion than planning skills, Booth began to hatch a plot so outlandish it sounded like the fevered scribbles of a rejected Gothic novel.

The first plan? Kidnap Lincoln. Yes, John Wilkes Booth actually believed he could snatch the President of the United States off the streets of Washington, smuggle him to Richmond, and use him as leverage to restart a dying war. It was less Mission: Impossible and more Mission: Improbable, and predictably, it fell apart faster than you could say “secession.” By April 1865, with the Confederacy crumbling and Robert E. Lee surrendering at Appomattox, Booth decided that subtlety was overrated. If he couldn’t save the South, he could at least make a statement—one written in blood.

So came the infamous night of 14 April 1865. Ford’s Theatre, Washington D.C. The play: Our American Cousin. The audience: packed. The President: seated in his box with his wife Mary Todd, oblivious to the fact that his final moments were ticking down with each line of comedic dialogue. Booth, thanks to his celebrity status, had unrestricted access to the theatre and knew its ins and outs better than the janitor. He crept into the President’s box during the play’s funniest line—a moment guaranteed to generate loud laughter—and fired a single shot into Lincoln’s head.

Then came the theatrics. Booth leapt from the balcony, caught his spur on the bunting, landed badly, and broke his leg. Undeterred, he raised himself, shouted “Sic semper tyrannis!” (“Thus always to tyrants!”), and made his dramatic exit. If he’d had a top hat and a spotlight, it would’ve been the stuff of Broadway.

The next twelve days became America’s first true media circus. Newspapers couldn’t print updates fast enough. Booth, now a fugitive with a broken leg and a bruised ego, fled through Maryland into Virginia. He was helped by Southern sympathisers, who either admired his audacity or were too confused to say no. He travelled by horse, wagon, and sheer stubbornness, sleeping in barns and scribbling into his diary like a man auditioning for the role of tragic antihero.

That diary, by the way, is a fascinating read—not because it contains any deep philosophical insight, but because it reveals just how far gone Booth really was. He truly believed he had acted nobly, that history would vindicate him, that the South would rise again and erect statues in his honour. Instead, his name became synonymous with betrayal and murder.

On 26 April, Union soldiers finally tracked him to a tobacco barn on the Garrett farm near Port Royal, Virginia. They surrounded the barn and demanded his surrender. Booth refused, of course. He wanted to die dramatically, preferably on his feet, in a hail of bullets or engulfed in flames. The barn was set on fire. A Union soldier named Boston Corbett, disobeying orders, shot Booth through a crack in the wall, severing his spine. He was dragged out, paralysed, dying, and allegedly whispered, “Tell my mother I die for my country.”

Even in death, the melodrama refused to quit.

The impact of Booth’s actions was seismic. Lincoln died the next morning, plunging a weary, war-torn nation into chaos. Reconstruction, which had already promised to be messy, became even more fractured without Lincoln’s guiding hand. Booth thought he was saving the South, but all he did was make everything worse. His bullet didn’t just end a presidency—it poisoned the fragile efforts to reunite a broken country.

In the years that followed, Booth’s name morphed from celebrity to synonym for villainy. His acting career, once so full of promise, was reduced to a grisly footnote. No statues were built, no theatres named in his honour. His family, especially his brother Edwin Booth—a Union loyalist and famed actor in his own right—was devastated. Edwin spent the rest of his life trying to scrub the blood from the Booth name, a tragic mirror of Shakespearean sibling drama if there ever was one.

And yet, Booth remains an oddly compelling figure—not because he was brave or noble, but because he embodied the terrifying power of ego unchecked. He reminds us what can happen when charisma meets fanaticism, when the applause of the crowd convinces a man he’s the centre of the world, even if that world is burning.

Today, Booth is remembered less as the dashing actor he once was and more as the assassin whose bullet shattered not just a skull but the illusion that America could easily stitch itself back together. His name lingers in history like smoke after a fire, not because he deserved it, but because his act forced the nation to confront its deepest wounds.

History, after all, rarely gives standing ovations to villains. But it never forgets them either.