How Friedrich Nietzsche Accidentally Invented Modern Angst

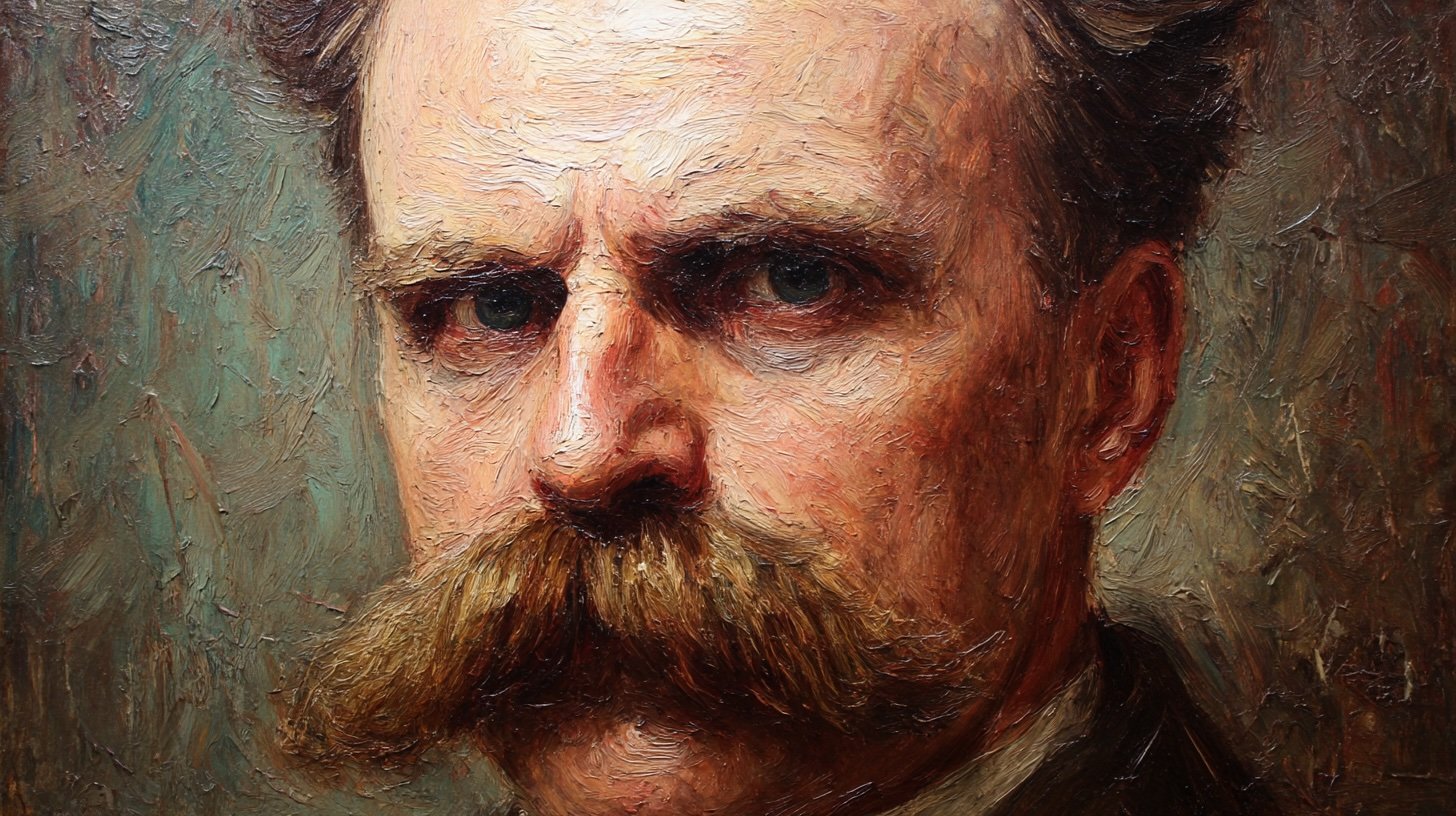

Friedrich Nietzsche never wanted to be famous. That would require tolerating people. But here we are, over a century later, still quoting the man who declared God dead, reinvented morality before breakfast, and weaponised aphorisms like a 19th-century Twitter addict with a grudge against Plato. Nietzsche’s shadow looms over modern thought like a brooding intellectual thundercloud—or perhaps more accurately, like a lonely man with a monumental moustache shouting into the abyss.

He wasn’t always shouting. In fact, young Nietzsche was a prodigy. At 24, he landed a professorship in philology at the University of Basel. He didn’t even have a doctorate. But his ability to dissect ancient texts with the enthusiasm of a caffeinated owl made him irresistible to the old academic guard. That didn’t last. By 35, his health had collapsed and he retired, opting instead for a nomadic life of solitude, illness, and scribbling out philosophical dynamite.

If Nietzsche had lived today, he’d be cancelled within minutes. The man was not here to coddle your worldview. He believed most people floated through life like compliant sheep. He called them the “herd.” And he didn’t mean it nicely. Nietzsche championed the rise of the “Übermensch,” a kind of self-made moral aristocrat who creates values instead of borrowing them. It has nothing to do with Superman and everything to do with radical self-overhaul. Not for the faint-hearted.

His writing style didn’t help his popularity among German philosophers, who generally preferred things verbose and unreadable. Nietzsche, by contrast, wrote like a man who wanted to etch his thoughts onto lightning bolts. His books read like scorched-earth monologues, full of sharp turns, fiery metaphors, and frequent swipes at Christianity. He considered it a religion for the weak. Cue the hate mail.

And yet, Nietzsche didn’t hate Jesus. He rather liked the man. What he couldn’t stomach was what he saw as the church’s betrayal of Jesus’ radical life. For Nietzsche, Christianity peddled guilt and obedience, promoting a morality based on ressentiment—a French word he repurposed to mean simmering resentment dressed up as virtue. Essentially, if your entire moral code is “I’m better because I suffer more,” Nietzsche was coming for you.

He also didn’t suffer fools gladly. Or anyone, really. His relationships were… strained. He fell madly in love with Lou Andreas-Salomé, a brilliant and independent Russian intellectual. She, sensibly, declined his proposal. Twice. After that, Nietzsche’s friendships unravelled like a cheap philosophy scarf. Even his close bond with composer Richard Wagner went sour. Nietzsche once worshipped Wagner, seeing him as a cultural revolutionary. Then Wagner found God and wrote an opera about it. Nietzsche, furious, wrote an entire book to roast him.

By the late 1880s, Nietzsche’s brain began short-circuiting. In 1889, he witnessed a horse being flogged in Turin. Overwhelmed, he threw his arms around the animal and wept. Then came the collapse. He never recovered. The remaining eleven years of his life were spent in the care of his mother and sister, drifting between catatonia and bursts of manic scribbling.

That’s when things got complicated. His sister, Elisabeth, took over his archive. A fan of nationalism and bad ideas, she repackaged his work to align with proto-Nazi ideology. The moustache didn’t help. It looked very Third Reich. But Nietzsche despised anti-Semitism. He called it “the sign of a weak mind.” If he’d lived long enough to see his name weaponised by goose-stepping ideologues, he’d have had a Nietzschean breakdown all over again.

Long before the moustache became a problem, Nietzsche had dabbled in music. Yes, he composed piano pieces. And no, they weren’t terrible. But they weren’t exactly Chopin either. A bit heavy-handed. You can almost hear the philosophy in the chords. His musical idol was, of course, Wagner, before their dramatic intellectual divorce.

He also didn’t drink coffee. This is the kind of fact that makes people uncomfortable. You expect a man who practically invented existential dread to mainline espresso. Not Friedrich Nietzsche. He preferred tea, walks in the mountains, and complete silence. His daily routine bordered on monastic. When not being struck down by migraines and gastric horror shows, he wandered Swiss and Italian landscapes like a tragic tourist looking for meaning.

He found meaning everywhere and nowhere. In books like Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche tried to create a new mythos, a kind of philosophical scripture. It failed miserably. No one read it. He self-published most of his works. They didn’t sell. By the time he collapsed in Turin, he was essentially unknown. Nietzsche was a commercial disaster.

Posthumous fame is a cruel trick. Friedrich Nietzsche became a sensation after he could no longer enjoy it. Suddenly, people were reading Beyond Good and Evil and The Birth of Tragedy like they were sacred texts. Freud admired him. So did Kafka. The French existentialists practically adopted him as a patron saint. Sartre, Camus, and even Foucault all owed him philosophical debt. He lit the fuse for modernism, then vanished into a silent, padded room.

He hated systems. “I mistrust all systematisers,” he said. “The will to a system is a lack of integrity.” Try getting a grant with that attitude. While Kant built majestic mental cathedrals and Hegel erected dialectical skyscrapers, Nietzsche preferred ruins. Shattered idols. He was more of a philosophical arsonist than an architect.

The moustache? Let’s talk about it. It was absurdly large, even by 19th-century standards. It looked like a caterpillar trying to escape his face. Students at the time mocked it. He refused to shave it off. Like everything with Nietzsche, it wasn’t just a moustache. It was a statement. A rebellion against bourgeois respectability. Or maybe it was just facial hair. Who knows?

He didn’t like democracy. He thought it promoted mediocrity. But don’t mistake him for a fascist. He didn’t want strongmen. He wanted strong minds. Nietzsche wasn’t interested in politics so much as inner revolutions. The only regime worth overthrowing was the one inside your skull.

In a rather Nietzschean twist, he wrote about eternal recurrence—the idea that life might repeat itself, endlessly, forever. Same joys, same sorrows, same bad haircuts. Would you say yes to that? He thought your answer revealed the quality of your soul. He didn’t offer comfort. And he offered a dare.

His writing invites confusion. That wasn’t an accident. Friedrich Nietzsche deliberately avoided clarity when it got in the way of poetry. He distrusted conclusions. He preferred provocations. Half the time, he sounds like he’s contradicting himself. The other half, he actually is. It’s like being philosophically gaslit by a genius with migraines.

He loved the Greeks. Not the moralising Socrates kind, but the pre-Socratic chaos. Heraclitus was his hero. Everything flows, nothing stays. Nietzsche took that and ran with it. Order is a lie, he insisted. Life is struggle. We grow by wrestling with it, not by hugging it.

One of his most famous lines, “What does not kill me makes me stronger,” has since become a motivational poster staple. Nietzsche would have loathed that. He didn’t mean it as a pep talk. He meant it as a dare to endure the abyss and come out the other side, if you can.

Nietzsche had a strange relationship with women. Aside from Lou Salomé, there weren’t many. He once wrote that women are not yet capable of friendship. Charming. And yet, he also said men haven’t understood women because they treat them like puzzles instead of people. Nietzschean feminism: complicated.

His last written words? A series of letters signed “Dionysus” and “The Crucified.” They went to everyone from Cosima Wagner to the Kaiser himself. They were wild, mystical, apocalyptic. The man had burned so brightly he incinerated his own mind. That, or syphilis finally caught up with him. The diagnosis remains unclear.

Despite the chaos, Friedrich Nietzsche still matters. He asked questions that haven’t gone away. How do you live without a divine blueprint? How do you create values without inherited rules? What happens when we lose faith in reason, progress, and morality itself? These aren’t old problems. They’re tomorrow’s problems.

Maybe that’s why we keep circling back to him, despite the prickliness. Friedrich Nietzsche was the philosophical equivalent of chilli peppers in your eyeballs—painful, but unforgettable. He didn’t offer solutions. He dared you to invent your own.

And somehow, across the cracked pages and cryptic aphorisms, he’s still whispering: “Live dangerously. Become who you are.”

Just maybe lose the moustache.