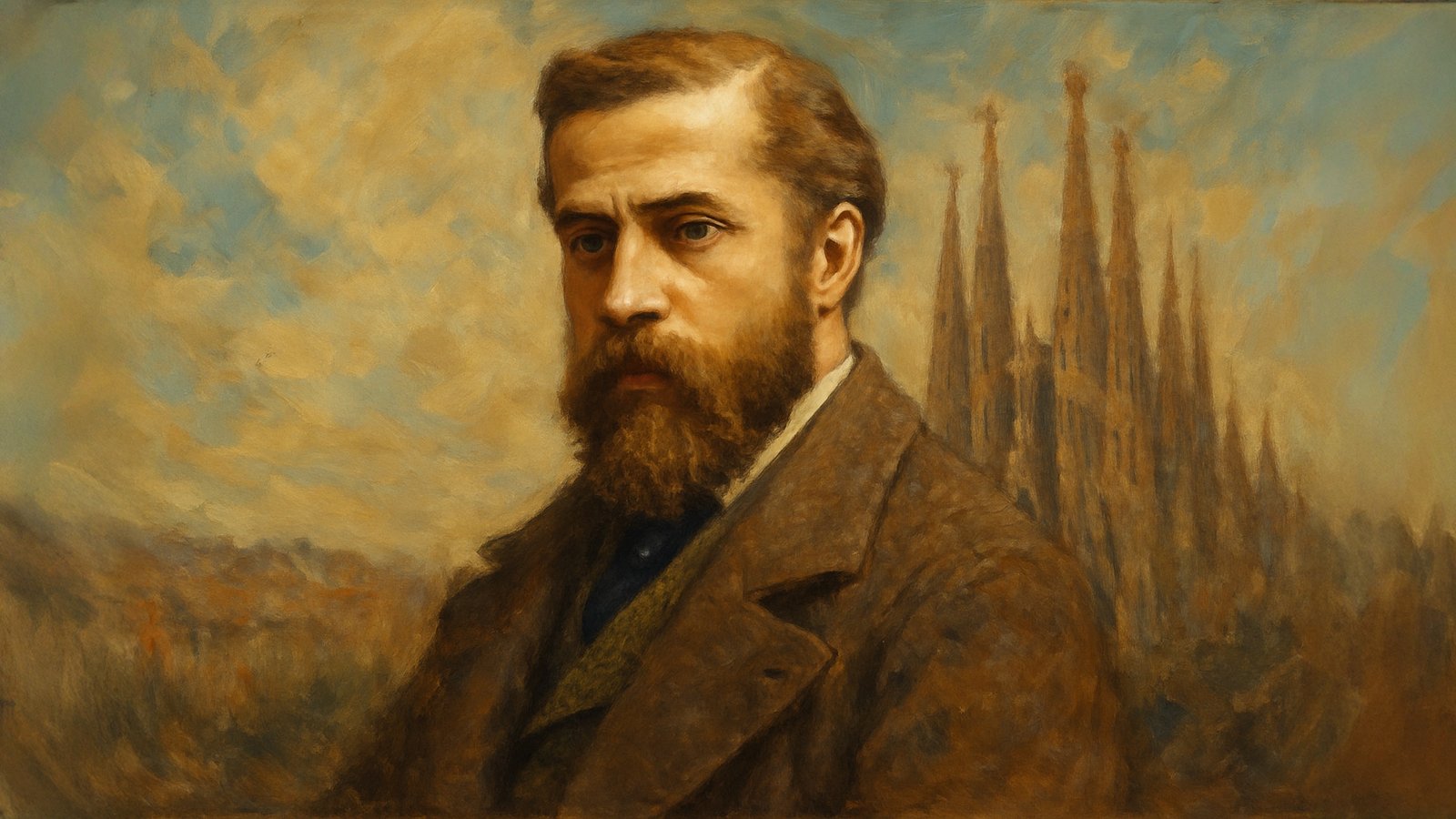

Gaudí: Beauty in the Curve

Antoni Gaudí, the man who made buildings melt, twist, shimmer, and spiral like the fever dreams of a very stylish dragonfly, was never just an architect. He was Catalonia’s answer to a magician, a visionary with a wild beard, and an allergy to straight lines. If Gaudí had a slogan, it would probably be something like, “Gravity is merely a suggestion,” or perhaps, “Why build up when you can grow?”

Born in 1852 in Reus, or possibly Riudoms—because even the place of his birth refuses to be confirmed like a true architectural mystery—Gaudí was the kind of child who spent more time staring at plants, bugs, and the curlicues of vines than socialising with other kids. He had rheumatic issues, so instead of football matches, his childhood was spent observing ants and sketching leaves. This wasn’t weird for him. This was research. Architectural foreshadowing at its finest.

He famously said, “Originality consists of returning to the origin,” which is what people say when their houses look like enchanted forests and they need to explain that to city planners. He also believed that nature was the ultimate teacher, which explains why half his buildings look like they were built by coral reefs with a degree in sculpture. Flowers, tree trunks, snails, honeycombs—you name it, he saw a floor plan in it.

He designed lampposts before he designed cathedrals. Not just any lampposts—impossibly elegant metal creatures for Plaça Reial in Barcelona. Most architects start with bland corporate lobbies. Gaudí? He went straight for luminous urban poetry. These lampposts remain standing today, looking like relics from a steampunk opera no one ever wrote.

His early career got a boost thanks to a twist of fate—or fashion. Eusebi Güell, a wealthy textile magnate, spotted a showcase of Gaudí’s designs and essentially went, “I don’t know who this guy is, but I want whatever he’s on.” The result? One of history’s great patron-architect bromances. Güell commissioned him for everything from wine cellars to city parks, and their collaborations are now UNESCO’s favourite hobby.

Gaudí never married. He flirted with celibacy like it was part of the Gothic Revival. He was engaged in the spiritual romance of flying buttresses and parabolic arches. When he wasn’t sketching or praying, he was walking. Long, contemplative walks, through fields or construction sites, depending on the mood.

Park Güell, his most famous not-a-park-but-actually-a-failed-housing-development, was meant to be a posh garden suburb. Only two houses were built. One was Gaudí’s own, and yes, it looks like a gingerbread cottage that got into a fight with a candy cane. Visitors today find mosaic lizards and winding staircases where there should have been quiet bourgeois living rooms.

He was deeply religious, but not in the “gently murmurs prayers” way. More in the “I will live in the Sagrada Família and become part of it until death or divine fusion” kind of way. He spent the last years of his life entirely devoted to that church. He was so committed he basically became a monk in a hard hat. His spirituality oozes from every turret and twisted spire.

Gaudí was extremely frugal. The man wore threadbare clothes, didn’t dine out, and refused to buy anything new. He was less “eccentric artist” and more “architectural hermit.” His pockets were usually full of string, sketches, and probably a small tile or two. Fancy wasn’t his thing—sublime was.

His attention to detail bordered on obsessive. He used strings weighted with birdshot and mirrors to model catenary arches upside down. That’s right—he designed buildings backwards to make sure the gravity worked out. He studied load-bearing stress with a level of commitment modern engineers reserve for bridge inspections.

Gaudí had a serious accident while walking to church in 1926. A tram hit him. Since he looked like a homeless man (he was famously dishevelled by that point), nobody rushed him to the hospital. Taxi drivers refused to take him. He died a few days later. The irony of a city losing its greatest modernist to its most boring form of transport is not lost on anyone. It’s the architectural equivalent of Shakespeare being hit by a library cart.

The Sagrada Família is still under construction nearly a century later, like the architectural equivalent of a child who won’t move out. Gaudí knew he wouldn’t finish it and shrugged, saying, “My client is not in a hurry.” That client being God, of course. It’s scheduled to finish in the 2030s—if the divine doesn’t request further revisions.

He believed colour was life. That’s why his buildings burst with ceramic shards, stained glass, and tiled lizards. He pioneered trencadís, a mosaic made of broken tiles, long before Pinterest boards made it trendy. He saw discarded pottery not as trash, but as pigment.

His Casa Batlló on Passeig de Gràcia? Locals call it the House of Bones. Its balconies look like skulls and its windows like vertebrae. It’s like walking into an elegant fossil. The roof looks like a dragon’s back. And you know what? That was the point. Gaudí loved myths almost as much as mortar.

He had synaesthesia before it was cool. He saw structures as music, space as rhythm, and stone as movement. It was less architecture, more choreography in concrete. You didn’t walk through a Gaudí building—you danced with it.

Gaudí didn’t draw blueprints the way other architects did. He preferred models, often sculpted in plaster or even soap. If he had lived today, he’d be the guy 3D-printing basilicas in his basement. His plans were living things, constantly reshaped, rethought, reimagined.

His obsession with nature wasn’t just visual. He studied how trees branch, how shells spiral, and how waves crash. Then he told columns to grow like trunks and ceilings to ripple like canopies. The man brought biophilic design into being before the term existed.

Gaudí was hit by a tram on Carrer de Bailèn. And yet, the city took its sweet time realising the crumpled body was their architectural messiah. He was taken to a paupers’ hospital. It wasn’t until a priest recognised him that the city snapped into mourning mode.

His funeral, however, was colossal. Barcelona turned out in droves. Thousands lined the streets. It was a reverse fairy tale: the humble old man they mistook for a nobody turned out to be the wizard of stone. Bells rang, crowds wept, and his body was carried to the Sagrada Família, where he now lies entombed.

He designed furniture as obsessively as he did façades. If you visit the houses he built, even the doorknobs have their own backstory and aesthetic arc. Every piece was sculptural, ergonomic, and vaguely enchanted.

The interior of La Pedrera (aka Casa Milà) looks like a sea cave mid-opera. The staircase feels like it’s breathing. The rooftop? It’s got helmeted chimneys that look like Martian warriors frozen mid-siege. At night, it feels like a dream you can walk around inside.

He refused to use straight lines. Said nature didn’t. It’s why his buildings feel like walking through hallucinations shaped by logic. If Escher and Tolkien opened an interior design firm, it’d still be less weird than Gaudí.

Gaudí predicted modern urbanism. He suggested vertical gardens, sustainable drainage, and solar energy way before it became fashionable to greenwash your skyscraper. He envisioned harmonious cities where nature and architecture didn’t just coexist—they tangoed.

He died aged 73, and now rests in the crypt of the Sagrada Família, eternally within the creation he gave his life to. Poetic, dramatic, and slightly terrifying—just like his buildings. Every tourist who visits adds another breath to the living cathedral.

His legacy? Unmistakable. People still argue whether Gaudí was a genius, a madman, or a prophet with a tile fetish. Barcelona, meanwhile, wouldn’t be Barcelona without his surreal skyline poking through the Mediterranean haze like a cathedral built by clouds. Or jellyfish. Or possibly divine whim.

So next time you’re in Barcelona and see a building that looks like it’s melting, growing, or politely defying gravity, tip your hat to the man who made weirdness sacred: Antoni Gaudí, the wizard who turned bricks into dreams. And remember—it’s not eccentricity if it works. It’s vision.