From Zorro to Robin Hood: How Douglas Fairbanks Invented the Movie Hero

Before there were superheroes in tights or action stars flexing their way through explosions, there was Douglas Fairbanks, the original swashbuckler who made audiences gasp, cheer, and sometimes faint a little. If cinema had a heartbeat in the silent era, it probably thumped to the rhythm of his sword fights and rooftop leaps.

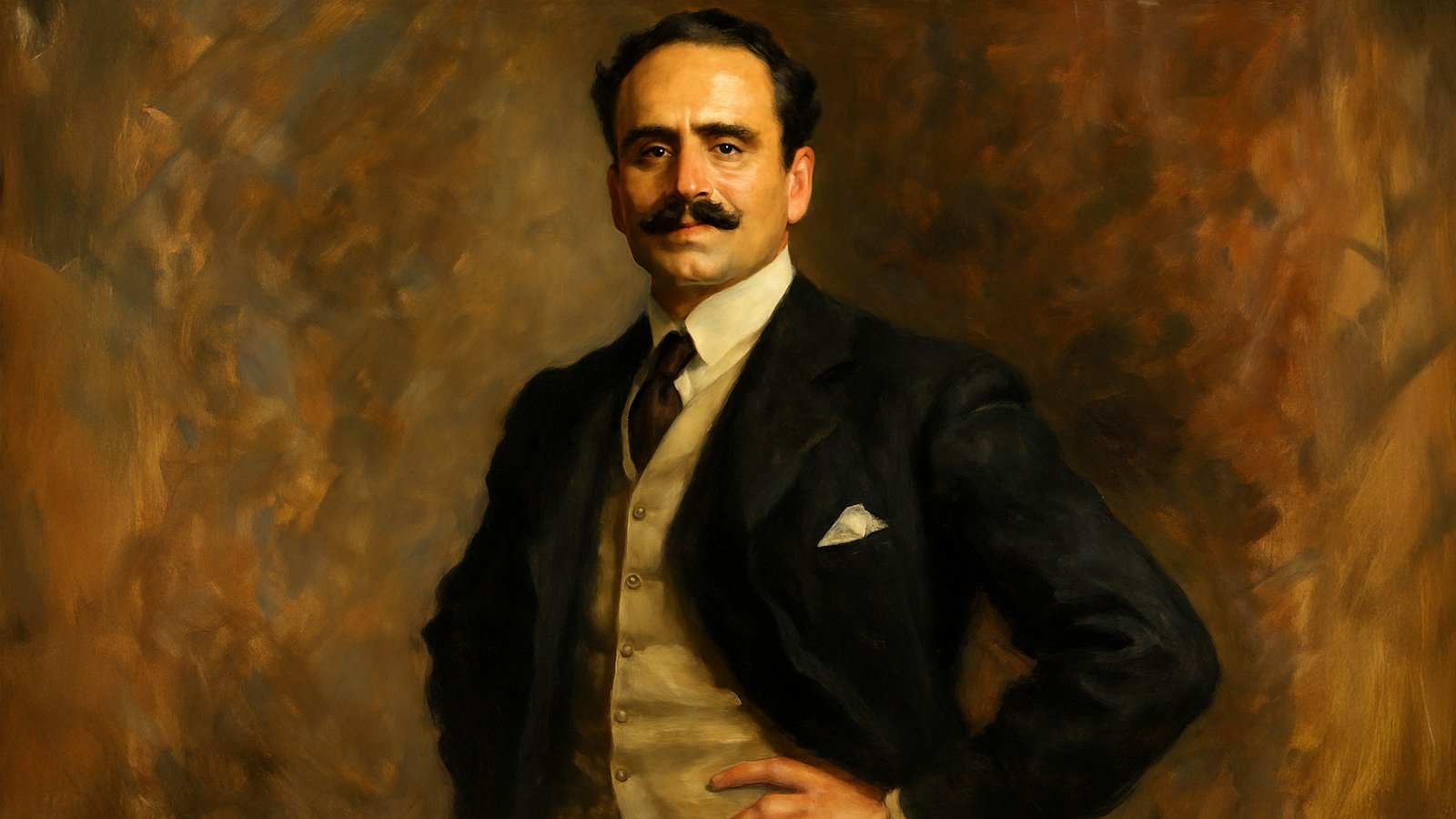

Born Douglas Elton Thomas Ullman in 1883 in Denver, he started life a long way from Hollywood glamour. His father disappeared early, his mother renamed the family after her first husband, and young Douglas soon discovered that pretending to be someone else was more fun than dealing with reality. He acted in school plays, then hit the stage properly at nineteen. By the time he reached Broadway, Fairbanks had the kind of charisma that could light gas lamps without matches.

He wasn’t the moody kind of actor who waited for inspiration; he was the kind who sprinted headfirst into it. In 1915, when movies were still finding their voice—or rather, didn’t have one yet—he made his screen debut in The Lamb. It was an instant success, mostly because audiences had never seen a man so fearless about jumping off furniture. Within a few years, Fairbanks had built an entire career on athletic exuberance. While other actors struck poses, he leapt over them.

The 1920s belonged to him. He was the man every boy wanted to be and every woman wanted to meet. When he played Zorro in The Mark of Zorro, he practically invented the masked hero. When he donned tights for Robin Hood, he became the embodiment of cinematic adventure. The Thief of Bagdad turned fantasy into a spectacle that would make CGI blush. His swordplay was choreography before Hollywood invented stunt coordinators. And let’s face it, his smile could have its own billing.

But Fairbanks wasn’t content just being the hero on screen. He wanted to rewrite the rules off it. In 1919, tired of studios bossing around creative people, he joined forces with Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and D. W. Griffith to found United Artists—a company run by artists, for artists. They may as well have called it the Revolution in Celluloid. United Artists gave filmmakers freedom long before the word became a slogan. Fairbanks wasn’t just swinging from chandeliers; he was swinging the balance of power in Hollywood.

And then there was Mary. Mary Pickford, America’s Sweetheart, the woman whose curls were as famous as his grin. Their 1920 marriage was a media explosion before paparazzi were a thing. Together they built Pickfair, a Beverly Hills estate that became ground zero for early celebrity culture. Royalty, politicians, and actors came to bask in the glow of their perfection. If you wanted to see what the Jazz Age looked like when it brushed its hair and wore diamonds, you went to Pickfair. The couple were Hollywood’s golden duo, the template for all future celebrity power couples—from Liz and Dick to Brangelina.

At the first ever Oscars in 1929, it was Fairbanks who hosted, wearing that effortlessly dashing smile that had made him cinema’s king. Ironically, that same year also marked the beginning of the end. The talkies arrived, and suddenly, everyone wanted actors who could speak as well as jump off battlements. Fairbanks’s larger-than-life physicality didn’t quite fit into the new, sound-filled Hollywood. The world that once adored his silent energy now demanded dialogue, and his poetic sword swooshes couldn’t compete with microphones.

He tried adapting, of course. The Iron Mask (1929) gave him one last hurrah—a parting salute to the age of swashbuckling silence. But by the early 1930s, his screen presence faded, replaced by younger, smoother voices. Fairbanks wasn’t built for obsolescence. For a man who once flew on carpets and scaled castles, sitting quietly was never an option. So he travelled, played tennis obsessively, and smiled bravely while the industry he helped build moved on without him.

Behind the famous grin, though, life wasn’t all sword fights and sunsets. His marriage to Pickford crumbled under the weight of changing times and changing people. She preferred quiet evenings; he still wanted adventure. They divorced in 1936, ending an era as much as a marriage. A few months later, he married Lady Sylvia Ashley, but by then, his health was in decline. In December 1939, Douglas Fairbanks died in his sleep at the age of fifty-six. The man who had once seemed immortal, forever leaping across screens, was gone.

Yet even in death, Fairbanks remained a symbol of eternal motion. Modern cinema still moves in his shadow. Every time an actor performs his own stunt, swings a sword, or grins through danger, there’s a little bit of Douglas in the frame. Errol Flynn, Cary Elwes, Johnny Depp, even Indiana Jones owe him a debt. Fairbanks taught Hollywood that adventure was not just a genre; it was a philosophy.

What made him different wasn’t just his athleticism, though that helped. It was the spirit behind it—a genuine belief that life was meant to be conquered with charm, energy, and a little bit of mischief. He didn’t play heroes; he embodied them. His films were love letters to optimism, written with daggers and laughter. In an age when technology limited spectacle, he expanded it through sheer enthusiasm.

Watching Fairbanks today feels almost surreal. No sound, no colour, no CGI—just one man defying gravity and expectation. His leaps weren’t just stunts; they were metaphors. In every bound and grin, he told audiences that limits were negotiable. It wasn’t just escapism. It was inspiration wrapped in adventure, dressed in tights.

He helped shape Hollywood into an empire of dreams. Without him, there might not have been a United Artists, an Academy Awards, or a notion that actors could also be business visionaries. His legacy isn’t only on the screen but in the very structure of modern cinema’s self-belief.

Fairbanks once said, “The man who has never made a fool of himself in love will never be wise in it.” He might as well have been talking about film itself. Cinema, like love, needs a bit of foolish bravery. And Fairbanks had that in abundance.

So, next time a superhero soars across a digital skyline or a pirate swings from a mast, remember the man who did it first—without special effects, without sound, and often without a stunt double. Douglas Fairbanks didn’t just make movies. He made movie stars, movie myths, and the notion that adventure belongs to those who leap first and look later.