Franz Schubert: The Quiet Genius

Franz Schubert wasn’t the most obvious candidate for musical immortality. He looked more like a shy bookkeeper than a genius composer, and quite frankly, he lived like one too. But despite his scruffy appearance, miserable bank balance, and tragically short life, Franz Schubert left behind a mountain of music that still has audiences weeping, swooning, and occasionally wondering how a man who never quite managed to leave Vienna still wrote with such enormous emotional range.

He was born in 1797 in the Vienna suburbs, the twelfth child in a family with so many kids that their dining table probably needed an overflow room. His father was a schoolteacher and fully intended little Franz to follow in his chalk-dusted footsteps. Which he did, briefly. Very briefly. Music had other plans.

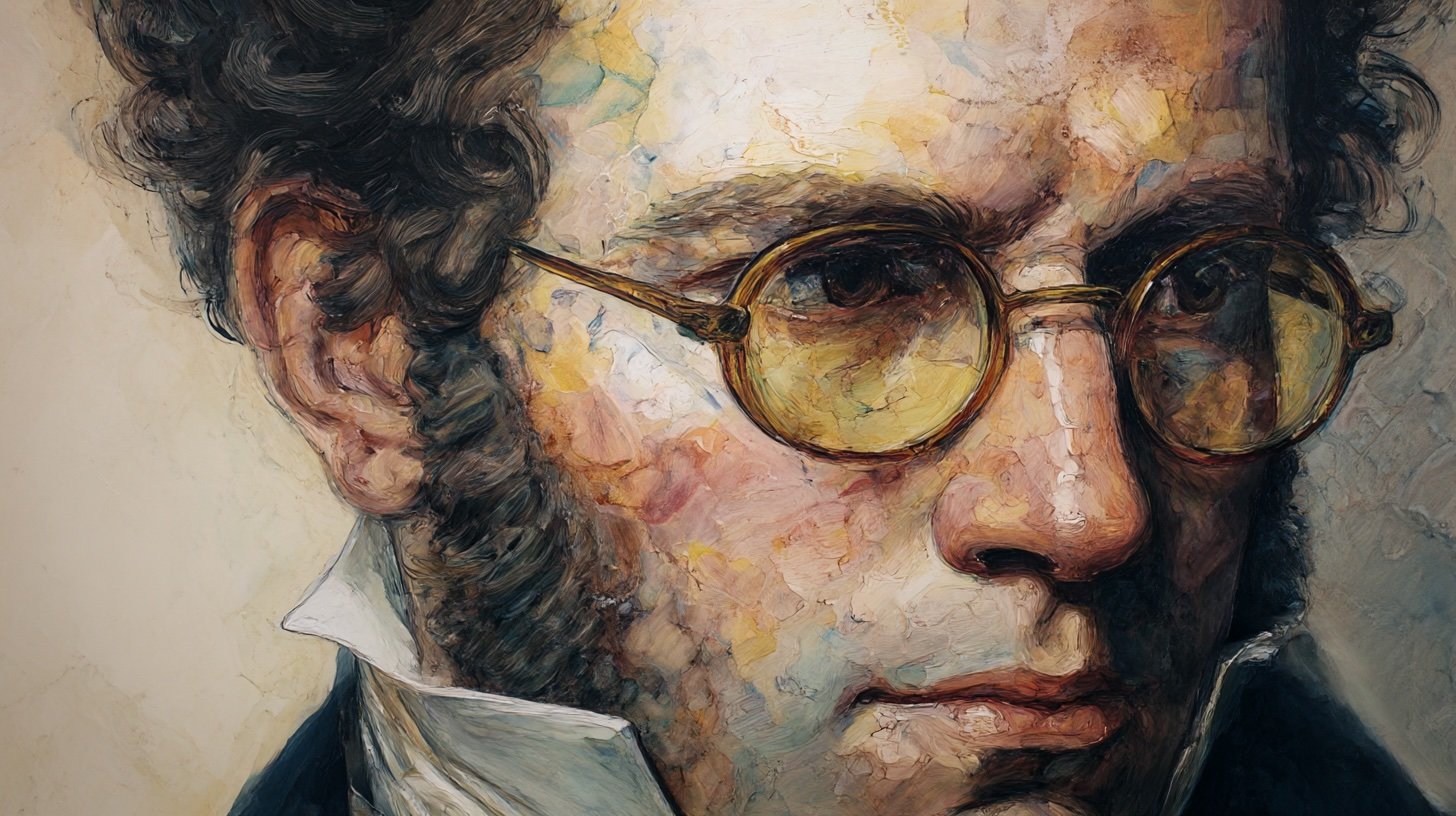

Young Franz was small, bespectacled, and unassuming. The kind of person who could enter a room and not disturb the air. Yet by age eleven, he was already playing the violin and composing at a rate that would give caffeine addicts a run for their money. By the time his voice broke (and with it, his place in the Vienna Court Choir), he was writing symphonies, string quartets, and operas like a man possessed. If possession by the ghost of Mozart were a thing, this would have been it.

The man wrote over 600 songs. Just let that sink in. Six. Hundred. That’s more than most people write emails in a decade. And these weren’t dashed-off ditties. These were the emotional soundtracks of a thousand heartaches, inspired by the great German poets like Goethe, Heine, and Rückert. The lieder—as the songs are called—don’t just set poetry to music; they bleed, ache, and tremble with feeling.

Take “Erlkönig” for example. It’s a musical rollercoaster featuring a terrified child, a spooky elf king, and a panicked father on horseback. All sung by a single singer, frantically switching characters. Add a piano part that gallops like a startled steed, and you have one of the most dramatic pieces in all of Romantic music—and no one dies more dramatically in song than a Schubert character.

But if you’re looking for a tragic arc, Schubert’s life is practically a textbook. He never married, was perpetually broke, and most of his music wasn’t even performed during his lifetime. He lived in shared apartments, survived on the kindness of friends, and routinely hawked his manuscripts for far less than they were worth. The world, it seems, took a while to catch up to his genius.

There were some high points. He was part of a creative gang called the Schubertiads—salon evenings where artists, poets, and musicians gathered to share art, get drunk, and argue about literature. These were intimate affairs filled with candlelight, wine, and melancholy. Perfect for the Romantic soul.

He adored Beethoven and finally met him shortly before Beethoven’s death. Legend has it, Schubert was so nervous he barely said a word. Beethoven, who was by then almost completely deaf, nevertheless recognised Schubert’s talent and supposedly muttered, “He has the divine spark.”

It’s not even clear how Schubert died. Syphilis is a strong contender. Mercury poisoning from syphilis treatment also gets a vote. Some even point to typhoid. Whatever it was, it took him at the tragically young age of 31. And yet, in those three decades, he produced over 1,500 works. That’s one every eight days. Without email, electric light, or caffeine pods.

His “Unfinished Symphony” is, hilariously, more famous because it’s unfinished. Two movements and then… nothing. Did he lose interest? Misplace the manuscript? Get distracted by a poem that needed musical dressing? No one knows, and that mystery just adds to its allure.

Then there’s “Winterreise” (Winter Journey), a song cycle that could depress even the chirpiest optimist. It’s a bleak, snowy wander through heartbreak, alienation, and existential gloom. But it’s magnificent. You don’t just listen to it. You survive it.

Unlike many tortured artists, Schubert did have friends. Lots of them. But he remained almost comically unsuccessful in his lifetime. He applied for musical positions and got politely turned down. He organised concerts, and audiences stayed home. Meanwhile, his music sat quietly in drawers, waiting for the world to wake up.

When it finally did, it fell hard. The so-called “Great” C major Symphony turned up years after his death, tucked in a drawer. Robert Schumann called it “heavenly length,” which was both a compliment and an accurate warning.

And yet, Schubert never conducted a large orchestra. Never toured Europe. Never owned a fancy hat. He just wrote. Constantly. In cafés, in taverns, on scraps of paper. One of his greatest works, the String Quintet in C, was published long after he died. Today it’s a regular on “top ten classical pieces of all time” lists.

Somehow he managed to create music that sounds like it knows your secrets. His melodies can be fragile as a spider’s web or as lush as an Alpine meadow in spring. He had a genius for turning everyday emotion into something eternal.

He wrote an entire mass during a summer holiday. That’s right. While most people worry about sunburn and overpriced ice cream, Schubert knocked out a sacred choral masterpiece.

Scholars still argue about his sexuality. Some believe he was gay or bisexual. Others say the evidence is inconclusive. What everyone agrees on is that he was lonely. Not tragic-hero lonely. Just quietly, deeply, heartbreakingly alone.

His portrait doesn’t scream charisma. He has mutton chops, a puddingy face, and the stare of someone thinking about a really good sandwich. And yet, that shy little man with terrible eyesight and a taste for beer wrote some of the most intimate music ever composed.

He loved theatre and tried his hand at opera. Unfortunately, his librettists were often terrible, and the results unremarkable. Unlike Mozart or Verdi, Schubert never found his “Don Giovanni” moment.

Still, he managed to revolutionise the German art song and change the trajectory of Romantic music. No big deal.

He’s buried next to Beethoven. Not bad company. In fact, he specifically asked to be buried near him. The fanboy energy was real.

Today, his face appears on Austrian coins, stamps, and school music room walls. Not bad for a man who once wrote music on borrowed paper while staying in a friend’s spare room.

Modern performers revere him. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Elly Ameling, Ian Bostridge—they all made careers interpreting his songs. And countless pianists have wrestled with his Impromptus, discovering just how deceptively hard “lyrical” can be.

If you’ve ever heard “Ave Maria” at a wedding, chances are it was Schubert’s version, albeit possibly mangled by a tenor with more enthusiasm than tuning.

He remains the patron saint of introverts, the composer for rainy days, unrequited love, and thoughtful train rides. Schubert reminds us that not all genius blazes like fire. Some of it flickers gently, just enough to warm the heart. And occasionally, make it ache too.