Chronotypes: Why Spanish Night Owls Sleep Better Than British Early Birds

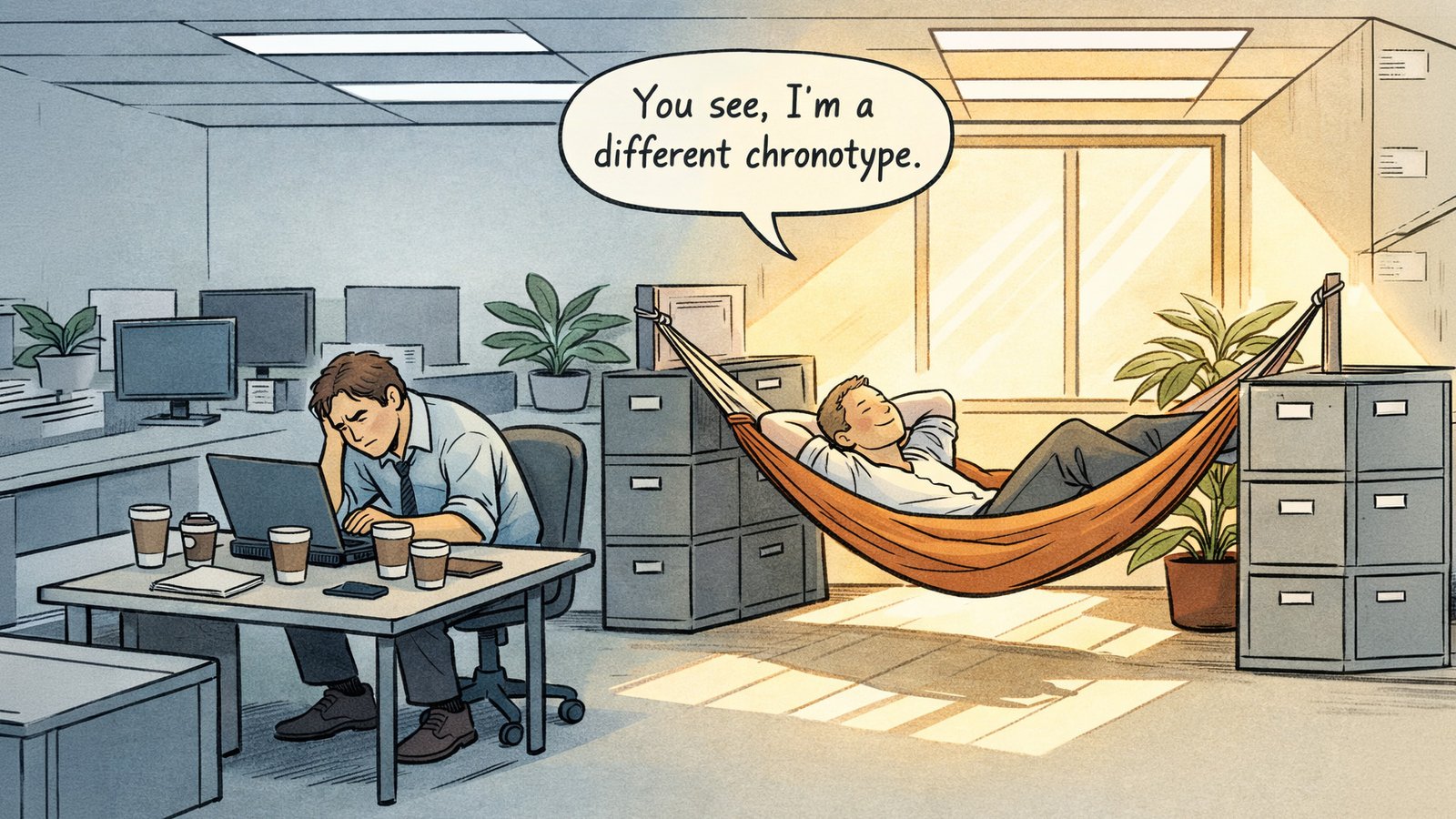

You’re sat at your desk at 8:30 in the morning, three coffees deep, and you’re still not firing on all cylinders. Meanwhile, your colleague bounces in like they’ve been possessed by the spirit of productivity itself. Perhaps you’ve wondered why some people seem biologically wired to thrive at dawn whilst you’re only just coming alive when everyone else is winding down. The answer lies in chronotypes – your body’s natural preference for when to sleep and wake. Interestingly, not every society wages war against these biological rhythms quite like others do.

Walk into a Madrid restaurant at 8 pm and you’ll find yourself dining alone, possibly being pitied by the staff. Most Spaniards won’t even think about dinner until 9:30 or 10 pm. Indeed, restaurants routinely serve meals past midnight. This isn’t just a quirky cultural habit – it’s an entire society organised around a rhythm that would send a 9-to-5 culture into fits. Spanish streets buzz with life well into the early hours. Children play in plazas at 11 pm, and nobody bats an eyelid. Similarly, these patterns emerge across Mediterranean and Latin American societies, where “evening” stretches far beyond what many Anglo cultures would consider reasonable.

These late-night cultures aren’t fighting their chronotypes – they’re accommodating them. Indeed, research shows that roughly 70% of people experience at least one hour of social jetlag per week. That’s the miserable feeling when your biological clock clashes with society’s demands. Evening chronotypes suffer the worst of it in rigid time cultures. These individuals are living in a state of permanent jetlag. Wolves trying to function in a world designed for larks, they drag themselves to 8 am meetings when their brains won’t truly wake up until noon.

Spain offers a masterclass in chronotype accommodation, though admittedly not everyone’s thrilled about it. The country’s labour minister recently caused a stir by calling it “madness” that restaurants stay open until 1 am. She’s got a point about hospitality workers, but she’s missing the bigger picture. Spanish culture has evolved around natural human sleep-wake cycles. It hasn’t forced everyone into the same mould. Meanwhile, the infamous siesta – that midday rest period – aligns perfectly with what sleep scientists call the post-lunch dip in circadian alertness. Between 2 pm and 5 pm, your body experiences a lull in energy. This happens regardless of whether you’ve eaten a massive paella or a light salad.

Only about 18% of modern Spaniards actually nap during siesta time. Instead, shops close, offices quiet down, and people get a break from the day’s heat and demands. This structural accommodation matters because it removes the pressure to maintain peak performance during a biological low point. Then, as evening arrives and temperatures cool, social life explodes. Families dine together without rushing. Friends linger over conversations. Finally, night owls feel like they’re living in sync with the world.

Italy follows a similar script with its riposo tradition, particularly in smaller towns and southern regions. Between 1 pm and 5 pm, you might find shops shuttered and streets quiet. Business owners go home for lunch, take a brief rest, then return refreshed for evening trade that extends well into the night. Northern Italy has shifted somewhat toward rigid schedules, yet the cultural memory of accommodating different energy patterns persists.

Japan presents a different flavour of chronotype flexibility through inemuri – the practice of sleeping whilst present. Spotted someone dozing on a Tokyo train? That’s not laziness; it’s culturally accepted strategic napping. Japanese workers often sleep in meetings, on park benches during lunch, or anywhere they can steal a few minutes. Society doesn’t judge this as slacking off. Rather, it’s seen as evidence of working so hard that rest must be grabbed wherever possible. Admittedly, this stems from Japan’s brutal work culture, but it also represents a tacit acknowledgement that humans can’t maintain constant alertness.

In contrast, British and American models operate differently. The 9-to-5 reigns supreme and deviation suggests poor character. Night owls in these cultures face constant judgment. They’re labelled lazy, undisciplined, lacking ambition. Yet science tells us chronotypes are largely genetic, not character flaws. Someone with an evening chronotype forcing themselves to wake at 6 am is fighting their biology. It’s like a morning person trying to work productively at midnight.

The damage this mismatch causes extends beyond mere tiredness. Studies link social jetlag to increased risk of obesity, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, and mental health problems. Evening chronotypes show higher rates of smoking and alcohol consumption. This isn’t because they’re inherently less healthy. Rather, they’re chronically sleep-deprived and stressed from constant misalignment with societal demands.

Fortunately, some companies are catching on. A German steel mill experimented with assigning shifts based on chronotype. Late types got evening shifts, early types got morning ones. Employees reported better sleep quality and improved wellbeing. The company saw productivity gains. Similarly, a Danish pharmaceutical company now provides nine-hour chronotype training sessions. Workers schedule demanding tasks during their natural peak times. They save email for their energy troughs. Consequently, employee satisfaction with work-life balance jumped from 39% to nearly 100%.

This concept of “chronoworking” is gaining traction. Rather than forcing everyone to clock in at 9 am, some organisations allow flexibility. Lions arrive at 7:30 am, whilst wolves roll in at 11 am but work later into the evening. The key insight is that most people need roughly the same number of working hours. It’s the timing that varies. Furthermore, research suggests that aligning work schedules with chronotypes can boost performance by 30%. People work when their brains are actually switched on.

Flexible work arrangements benefit more than just individuals. When teams span multiple chronotypes, you can achieve extended coverage without burning anyone out. Handovers become natural. Morning people handle early tasks, whilst evening types tackle late-day crises. This works particularly well in global teams where time zones already necessitate staggered schedules.

Yet resistance persists. Managers worry about coordination, about not having everyone available at once. Traditional corporate culture equates presence with productivity. It values “face time” over actual output. This presenteeism culture particularly harms evening chronotypes who must arrive early to be seen as committed. They struggle through unproductive morning hours. Eventually, they hit their stride just as everyone else leaves.

Sleep researchers advocate for core hours – perhaps noon to 3 pm when everyone’s present for key meetings. Flexible edges accommodate different chronotypes. This isn’t revolutionary; it’s simply acknowledging biological reality. Most people fall somewhere in the middle of the chronotype spectrum. They generally follow solar patterns. However, it’s the extreme morning larks and dedicated night owls who suffer most under rigid scheduling.

Schools face even greater challenges. Teenagers naturally shift toward later chronotypes during adolescence. Yet most schools start brutally early. Studies show that delaying school start times improves academic performance. It also reduces car accidents amongst teenage drivers and decreases depression rates. Nevertheless, changing school schedules proves difficult despite clear evidence of harm to young people’s health and learning.

The COVID-19 pandemic inadvertently ran the world’s largest chronotype experiment. Suddenly, millions worked from home with flexible schedules. Research found that evening chronotypes experienced improved sleep quality. They also had reduced depression rates. Freed from early morning commutes and rigid office hours, people naturally gravitated toward their optimal rhythms. Now, as companies push for return-to-office mandates, they’re essentially demanding that evening types return to chronic sleep deprivation.

Mediterranean and Latin American cultures didn’t consciously design their schedules around chronobiology. They evolved these patterns through climate, tradition, and social preferences. Nevertheless, they’ve created systems more aligned with human biological diversity. Eating dinner at 10 pm isn’t objectively better or worse than eating at 6 pm. It’s simply different, and it accommodates people whose energy peaks later.

Chronotype flexibility doesn’t mean abandoning structure entirely. Societies still need coordination and shared schedules. Rather, it means recognising that one-size-fits-all approaches cause unnecessary suffering. Evening chronotypes forced into morning schedules aren’t simply inconvenienced. They’re experiencing genuine circadian misalignment with measurable health consequences. We wouldn’t force left-handed people to write with their right hands. Yet we routinely demand that night owls function as morning people.

Some myths deserve dispelling. Night owls aren’t lazy; they’re biologically programmed differently. Morning larks aren’t morally superior; they’re simply fortunate that society’s default schedule suits them. Recent research has even identified five distinct chronotype subtypes rather than just two categories. Human sleep diversity is richer than we thought. Additionally, chronotypes shift throughout life. Children tend to lean toward morning types. Teenagers swing dramatically toward evening preferences. Adults gradually shift back toward morning as they age.

The path forward isn’t everyone adopting Spanish dining hours or Japanese napping practices. Different solutions suit different contexts. However, cultures that build flexibility into their rhythms demonstrate that accommodation is possible. Whether through extended evening social life, afternoon business closures, or accepted public napping, they’ve reduced chronotype conflict. They haven’t changed biology. Instead, they’ve accepted it.

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether you’re an early bird or night owl. It’s whether your society crushes half its population under mismatched schedules or adapts to reality. Humans experience the 24-hour day differently. Some cultures have stumbled into accommodation; others remain rigidly opposed. As flexible work becomes more common and research continues, perhaps more societies will recognise that fighting biology is a battle nobody wins.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.