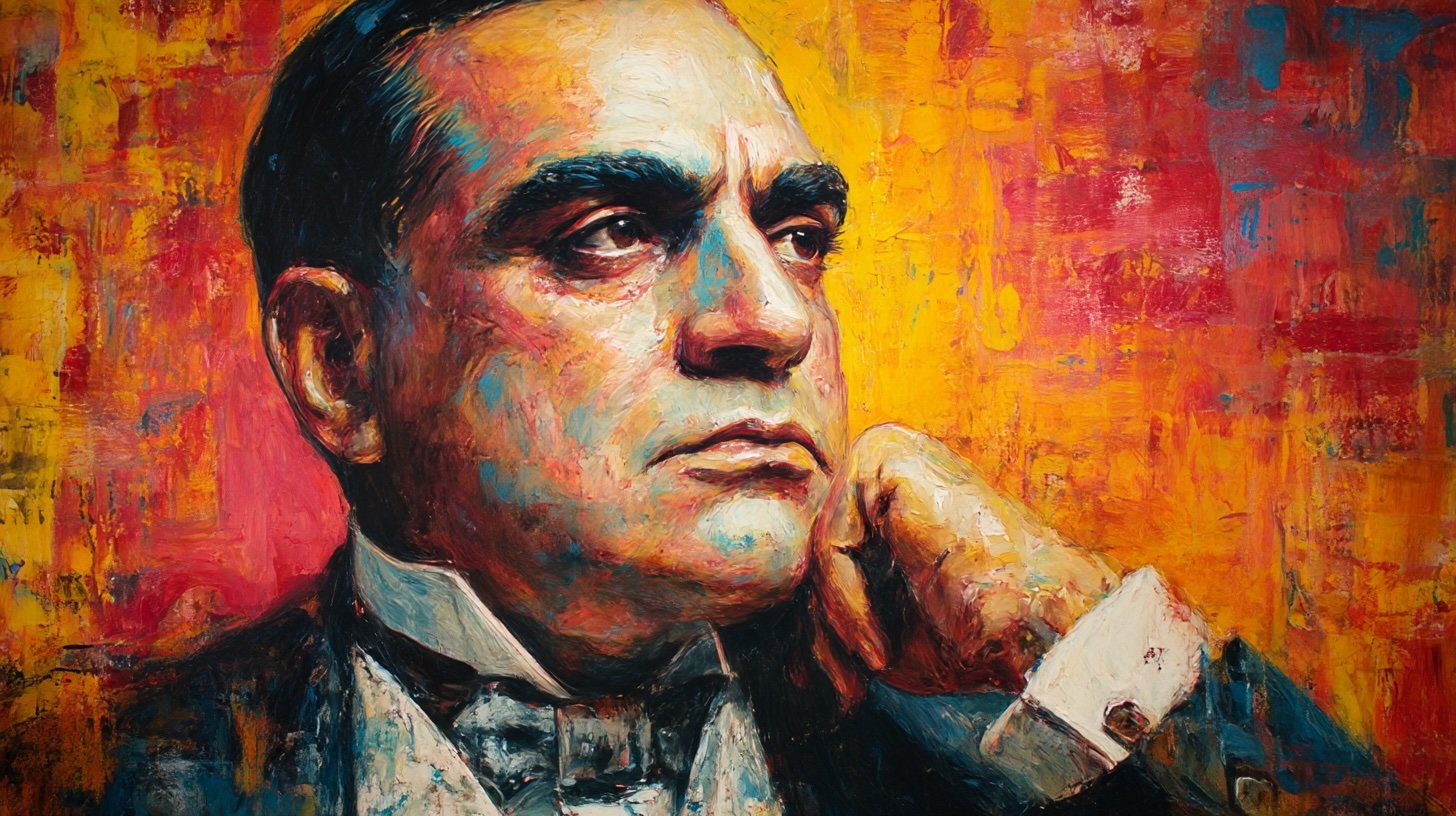

Caruso: The Tenor Who Made the World Listen

Enrico Caruso wasn’t just a tenor. He was the tenor—the human megaphone who somehow made phonographs sexy and crying into your scarf a global pastime. Before Spotify, before radio, before your neighbour’s Bluetooth speaker ruined brunch, there was Caruso, belting high Cs like his rent depended on it. He sang his way into history, hearts, and—somehow—the Guinness Book of Records.

Born in Naples in 1873, Caruso wasn’t supposed to be famous. His mum wanted him to become an engineer. But he did what any self-respecting Italian mamma’s boy would do: he sang in church to keep her happy, then sneakily turned that angelic voice into a career. He debuted on stage in 1895, and by 1903, he was the first global music superstar. Not bad for a kid from the slums of Naples with a penchant for practical jokes and homemade pasta.

Let’s start with the voice. Caruso’s voice wasn’t just powerful—it was magnetic. People described it as golden, burnished, masculine, and haunting. The sort of voice that could seduce you and shame you simultaneously. Scientists have actually analysed his recordings to understand his vocal magic. The secret? A weirdly perfect mix of overtones that even trained tenors drool over.

He was the first recording star. Literally. In 1902, he cut ten discs for the Gramophone & Typewriter Company in Milan. Each record sold like hot taralli, and the industry never looked back. By 1921, more than a million Caruso records had been sold. He didn’t invent the record player, but he certainly gave people a reason to own one.

He practically made the Met. At a time when opera was still flirting with elitism, Caruso drew crowds that didn’t care whether you wore tails or torn trousers. When he sang at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, tickets sold out weeks in advance. On one occasion, the crowd shouted so loud that the soprano had to wait for him to finish bowing before starting her aria.

His lungs were insured. Yes, Lloyd’s of London insured his lungs for $250,000—a staggering sum in early 20th-century terms. Today, that’s about the cost of a decent flat in central London or one avocado toast in Notting Hill.

He sang for the troops in World War I. While some prima donnas dodged war zones like bad reviews, Caruso performed for American soldiers, bringing Puccini to muddy trenches and shattered hearts. You’d think soldiers wanted jazz or ragtime, but no—they wanted Caruso. He made Verdi sound like a victory march.

He had a thing for monkeys. No, seriously. Caruso was a notorious animal lover with a special fondness for monkeys. He kept several as pets, dressed them up, and let them run wild in his hotel rooms. Hotel managers? Less fond.

His humour was chaotic. Caruso loved practical jokes. Once, he sent unsigned caricatures of the Metropolitan Opera staff to a newspaper, causing minor scandal and major laughter. His drawing skills were actually solid. If the singing hadn’t worked out, he might’ve become a cartoonist.

He made people faint. Literally. There were audience members—usually women, occasionally men—who swooned during his performances. Whether from the heat, the arias, or sheer operatic overload, fainting became a recurring theme at his concerts.

He hated his profile. Caruso believed he was unattractive, especially in profile. He preferred to be photographed from one side only. The irony? His face ended up on postcards, posters, candy tins, and opera house walls across three continents.

He survived a deadly earthquake. Caruso was in San Francisco in 1906 when the great earthquake struck. He escaped unharmed but was so traumatised that he vowed never to return. He also reportedly declared, in the middle of the rubble, “I want to go home!” Which—given the circumstances—is fair.

He was a tech nerd. Caruso adored gadgets. He embraced the phonograph with enthusiasm and constantly sought ways to improve sound quality. If alive today, he’d probably have three podcasts and an aggressive Twitter following.

His funeral was mobbed. When Caruso died in 1921 at age 48, Naples shut down. Over 100,000 people lined the streets. Traffic halted. Businesses closed. It was part state funeral, part religious procession, part group sob. The city hadn’t mourned that hard since Vesuvius exploded.

His voice was sent to space. Well, sort of. NASA included a Caruso recording on the Voyager Golden Record, the one beamed out to aliens in 1977. Somewhere, some extra-terrestrial life form might be grooving to “Vesti la giubba” without understanding why they suddenly feel sad and full of pasta.

He was a fashion icon—by accident. Caruso never tried to be stylish, but his slicked hair, impeccable suits, and opera capes made him a trendsetter. Italian men copied his moustache. New York dandies copied his silk scarves. He was basically the Pavarotti of Pinterest.

He inspired Hollywood. The 1951 film The Great Caruso starred Mario Lanza as the man himself and turned a new generation into opera buffs. Caruso never saw it—he was too dead—but the film made his legend feel fresh again, complete with swelling violins and exaggerated accents.

He never fully recovered from a stage accident. In 1920, a collapsing set piece injured him during a performance. He kept singing, of course—because opera doesn’t stop for trivial things like internal bleeding. But complications from that injury contributed to his early death.

He drank raw eggs. Like Rocky, but classier. Caruso reportedly drank raw eggs before every performance to coat his throat. This was pre-avocado smoothie days, when the truly committed vocalists embraced poultry-based power-ups.

He didn’t read music fluently. Despite his fame, Caruso was no musical savant. He had a great ear, but he relied heavily on repetition, coaching, and his phenomenal memory. Proof that natural talent and obsessive rehearsal beat fancy diplomas.

He hated critics. Especially one who wrote, after an early show, that he sang “from the stomach, not the heart.” Caruso responded by excelling to a point where critics had to eat their quills. He didn’t forget either—he’d sometimes recite bad reviews and laugh about them over dinner.

He recorded with a megaphone. Early recording tech was primitive. Caruso had to sing into a giant horn, basically a musical funnel, while trying not to move too much or blow it out with volume. Still, the recordings remain stunning. That’s vocal discipline—and lung power.

He was a hopeless romantic. He had several high-profile affairs and a complicated personal life. His letters to lovers, though, were full of longing, flowery language, and a surprising amount of culinary metaphors. Nothing says “I miss you” like “Your voice is as sweet as cannoli cream.”

He turned tears into cash. His recording of “Vesti la giubba” from Pagliacci—yes, the sad clown one—became the first sound recording to sell over a million copies. Basically, he monetised misery. Every broken heart had its own aria.

He might’ve been the first meme. Caruso caricatures, imitations, and spoof acts were everywhere. If you lived in 1910 and didn’t have a Caruso impression, were you even socially relevant?

He still sells records. Long after his death, Caruso remains one of the best-selling classical artists of all time. Digitally remastered versions of his recordings are available on every major platform. Somewhere, someone is still weeping over that tenor vibrato—probably with a cat and a glass of Barolo.

Enrico Caruso didn’t just sing. He made the 20th century sound better. He took opera out of the velvet box and gave it to the people, monkeys and all. Whether you hear him in a concert hall, a dusty old record, or a spacecraft passing Pluto, one thing’s for sure: when Caruso sang, the world didn’t just listen—it felt.