Bad Cholesterol: Why LDL Gets the Blame and What Actually Works

Bad cholesterol sounds like the villain in a children’s book. A bit smug. Slightly greasy. Probably wears a cape and lurks near takeaway menus. In real life, though, “bad cholesterol” usually means LDL cholesterol, a microscopic courier service that delivers cholesterol around your body. Cholesterol itself doesn’t wake up and choose chaos. Your body needs it for cell membranes, vitamin D, and hormones. You would rather keep it, thanks. The problem starts when too many LDL particles circulate for too long and your arteries end up acting like badly managed storage units.

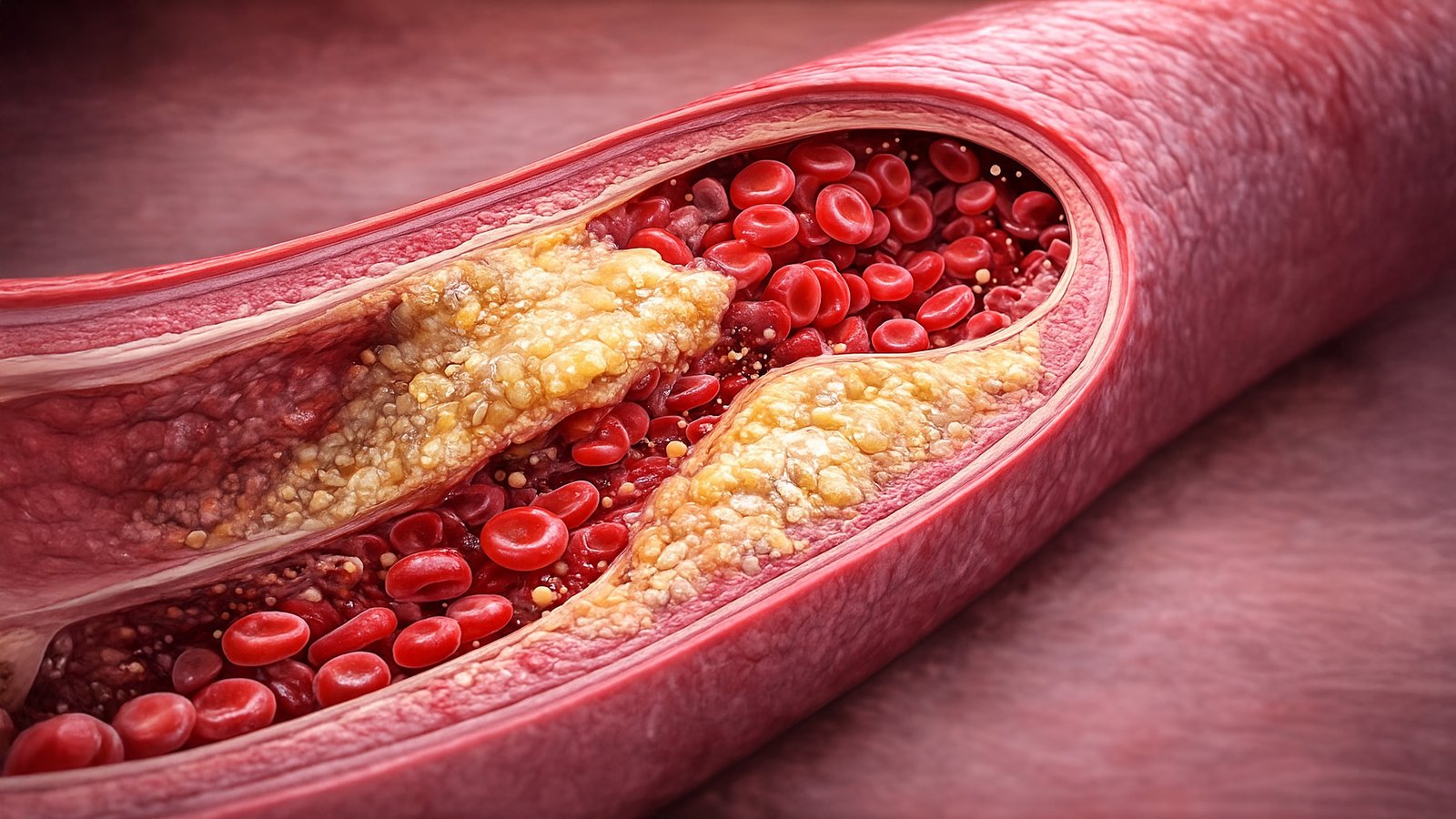

Imagine the motorway network of your body. Arteries carry oxygen-rich blood to where it needs to go. They should stay smooth inside, like a freshly cleaned water pipe. When LDL cholesterol stays high, cholesterol can lodge in the artery wall. Over time, that can spark inflammation and the build-up of plaque. Plaque doesn’t look dramatic when it begins. It looks like slow, boring clutter. Then one day the clutter becomes a blockage, and the consequences stop being boring.

The awkward part: high LDL rarely sends you a warning text. No “hey mate, your coronary arteries feel a bit tight today.” Most people find out through a blood test, often after years of feeling perfectly fine. That’s why the whole topic has this irritating vibe: the thing that matters doesn’t announce itself.

So what even is LDL, and why does it get the “bad” label? Lipoproteins are little packages made of fat and protein, designed to move fats around in water-based blood. LDL stands for low-density lipoprotein. In simple terms, LDL tends to ferry cholesterol from the liver out to the body. HDL, high-density lipoprotein, tends to ferry cholesterol back towards the liver. That’s why people call HDL “good cholesterol”, even though it doesn’t wear a halo and play the harp.

If you want to sound like you’ve read the small print on a lab report, you’ll hear about non-HDL cholesterol too. Non-HDL is your total cholesterol minus HDL. It captures the whole cast of atherogenic particles, not just LDL. Lots of clinicians like it because it doesn’t get distracted by one number and miss the bigger pattern.

Now, a reality check before we start banning every enjoyable meal: risk isn’t a single cholesterol number floating in space. Your overall cardiovascular risk depends on things like age, blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes, kidney disease, family history, and whether you’ve already had a heart attack or stroke. Someone can have a modestly raised LDL and still need aggressive treatment because their overall risk sits high. Someone else can have the same LDL and start with lifestyle changes first. Cholesterol loves context.

Let’s talk numbers, because cholesterol advice without numbers becomes a vague wellness fog.

You’ll often see LDL described like this in many reference ranges. “Optimal” sits below about 100 mg/dL, which is roughly 2.6 mmol/L. “Very high” starts around 190 mg/dL, about 4.9 mmol/L. In the UK, you’ll also see general-public messaging around aiming for LDL below roughly 3.0 mmol/L, with tighter targets for higher-risk people. If you’ve already got cardiovascular disease, clinical targets can be stricter still. You might hear targets like LDL at or below 2.0 mmol/L in secondary prevention settings, depending on guidance and individual circumstances.

That range of targets can feel confusing, like cholesterol has joined the school system and now grades you differently depending on which class you’re in. The reason sits in what doctors actually care about: preventing heart attacks and strokes, not winning an LDL beauty contest.

The history of cholesterol as a public obsession has a surprisingly soap-opera streak. In the mid-to-late twentieth century, researchers started linking population-level cholesterol patterns to heart disease rates. Over time, evidence piled up from clinical trials showing that lowering LDL reduces cardiovascular events. This relationship became one of the sturdier bridges between a blood marker and real-world outcomes. Different medications reduce LDL in different ways, and when trials keep showing fewer heart attacks when LDL drops, the idea gains weight.

That’s also where the biggest modern misunderstanding comes from. People sometimes argue as if the only evidence is about statins, therefore all cholesterol talk equals a statin marketing campaign. But the link between lowering LDL and reducing risk shows up across multiple drug classes and multiple trial settings. The story doesn’t depend on one pill alone.

Still, you don’t need a pharmacy to start shifting your cholesterol story. Lifestyle changes can make a real dent in LDL for many people, especially if your numbers sit in the mildly to moderately raised range. The key word there is “many”. Genetics can be stubborn. Some bodies produce more LDL, clear less of it, or handle lipids in ways that ignore your best intentions with porridge.

So how do you “fight” bad cholesterol without turning into the person who brings their own oat bran to dinner parties?

Start with the most powerful dietary lever: saturated fat.

Saturated fat tends to raise LDL cholesterol. It shows up in things like butter, ghee, fatty cuts of meat, many pastries, and a lot of processed foods that taste like comfort and regret. The goal isn’t to become frightened of every molecule of fat. The goal is to change the balance.

Swap saturated fats for unsaturated fats.

Unsaturated fats include monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. You’ll find them in olive oil, rapeseed oil, nuts, seeds, avocados, and oily fish. This swap matters because it doesn’t just remove something. It replaces it with something helpful. That replacement is where people often go wrong.

If you cut saturated fat and replace it with refined carbohydrates, you may not get the LDL drop you want, and you might nudge triglycerides up. That’s how someone ends up eating low-fat biscuits while feeling morally superior. Their arteries do not clap.

The second dietary lever: soluble fibre.

Soluble fibre acts like a polite sponge in your digestive system. It binds to bile acids and cholesterol-related compounds, and your body uses cholesterol to make more bile acids. That can reduce how much cholesterol circulates in your blood. You can get soluble fibre from oats, barley, beans, lentils, chickpeas, apples, citrus fruit, and plenty of vegetables.

This is why oats keep popping up in cholesterol conversations like an eager golden retriever. Yes, porridge helps. So do beans. So does building meals that look like they came from an actual plant.

There’s also a more “engineered” version of this approach: plant sterols and stanols. They can reduce cholesterol absorption. You’ll see them in certain fortified foods, spreads, and yoghurts. Some people find them useful, especially if they want a specific tool to target LDL.

Put these ideas together and you get what some researchers call a “portfolio” approach: combine multiple cholesterol-lowering foods rather than relying on one magic ingredient. In real-life terms, it means meals that regularly include soluble fibre, nuts, plant protein, and healthy fats. It’s less a diet and more a consistent pattern.

Now for the uncomfortable truth: you can do everything “right” and still have high LDL.

If you have familial hypercholesterolaemia, for example, your LDL can run very high from a young age because of inherited differences in LDL clearance. In those cases, lifestyle changes help, but medication often becomes essential. A rough red flag for clinicians is LDL at or above about 4.9 mmol/L, especially with a family history of early heart disease. That number doesn’t mean doom. It means: take this seriously and get properly assessed.

Exercise doesn’t always crush LDL on its own, but it improves the overall risk picture.

Regular activity can help with weight, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, inflammation, and general cardiovascular fitness. Some people see modest LDL improvements. Many see improvements in triglycerides and HDL. Even when LDL hardly moves, the body gets better at handling fats and sugar. Cardiovascular risk doesn’t live on one spreadsheet column.

Weight loss can reduce LDL in some people, especially when it shifts diet quality and reduces saturated fat intake. The trick is to chase sustainability, not punishment. A weekly routine you can keep matters more than a heroic month of suffering.

Now we need to talk about alcohol because it loves to sneak into cholesterol conversations wearing a clever disguise.

Alcohol affects lipids in a complex way. Moderate alcohol can raise HDL, which sounds nice until you remember HDL doesn’t grant immunity. Alcohol can also raise triglycerides, especially at higher intakes. It can add calories, worsen liver fat, and contribute to blood pressure issues. If someone has high triglycerides or struggles with weight, cutting back on alcohol often improves the overall metabolic picture. If you enjoy a drink, aim for sensible limits and treat it as a risk factor you can adjust rather than a personality trait.

Let’s address the big medication debate because it’s always there, hovering like a relative who insists they read “a study” on Facebook.

Statins reduce LDL by lowering cholesterol production in the liver and increasing LDL receptor activity. They have a large evidence base for reducing cardiovascular events, particularly in higher-risk people. Yet statins also attract a storm of misinformation and fear.

Some people experience side effects, including muscle aches, and those concerns should never get dismissed with a shrug. Clinicians can adjust dose, switch statin type, try alternate dosing schedules, or consider additional medications. The point isn’t to bully someone into swallowing a pill. The point is to use a risk-reduction tool thoughtfully.

NHS pathways often describe expected LDL reductions by statin intensity. High-intensity statins can reduce LDL by more than 40%. Medium intensity tends to sit around 31–40%. Those are broad expectations, not guaranteed outcomes for every body. Still, they explain why statins remain a foundation in prevention strategies.

If statins aren’t enough, or someone can’t tolerate them, clinicians can add other options such as ezetimibe, which reduces cholesterol absorption, or more specialised therapies in certain high-risk cases. The landscape has expanded beyond “statins or nothing”, even if the public conversation hasn’t caught up.

Now for one of the more niche controversies that matters in the UK: targets.

People sometimes compare UK guidance to international guidelines and notice that targets can differ. UK guidance often weighs cost-effectiveness strongly, especially in publicly funded healthcare. Some charities and specialists argue for more aggressive targets, particularly in secondary prevention. Others emphasise practical implementation and population impact. It can sound like an argument about decimals, but it reflects real trade-offs about resources and risk.

So what should you actually do tomorrow morning, besides panic-Google your last blood test? Get clarity on your numbers. Ask what your LDL is, what your non-HDL is, what your triglycerides are, and whether your clinician thinks you sit low, medium, or high risk overall. If you don’t know your blood pressure, check it. If you smoke, you already know what I’m going to say and you also know you don’t want to hear it. Build a cholesterol-friendly eating pattern that doesn’t make you miserable. Think of it as upgrading the default settings. Choose cooking fats that tilt unsaturated, such as olive or rapeseed oil, rather than butter or ghee most days. Keep butter as a flavour accent rather than the foundation of civilisation.

Make oats or barley show up a few times a week. You don’t have to eat porridge every day like you’re training for a Victorian workhouse. Oats can become overnight oats, muesli, oatcakes, even a handful blended into smoothies if you must.

Add beans and lentils regularly. If you already love chilli, dhal, soups, salads with chickpeas, or lentil stews, you’re basically doing cholesterol support without branding it.

Eat nuts sensibly. A small handful of almonds, walnuts, or mixed nuts can replace less helpful snacks. Nuts are calorie-dense, so think “supporting actor”, not “main character”.

Keep an eye on ultra-processed foods that hide saturated fat. Many people focus on the obvious butter and cheese while ignoring that pastries, biscuits, and certain ready meals can carry a sneaky saturated fat load.

Move your body in a way you’ll repeat. A daily brisk walk, regular cycling, swimming, dancing in the kitchen while you pretend you’re not dancing, strength training twice a week, whatever works. Consistency beats intensity. The heart loves boring routines.

Don’t chase HDL as if it’s a magic shield. You’ll sometimes hear people brag about very high HDL. It can be fine, but it doesn’t guarantee protection. In some cases, extremely high HDL doesn’t add extra benefit. Focus on lowering LDL and non-HDL where needed and improving overall risk.

Be suspicious of the “one weird trick” economy. Coconut oil isn’t a loophole in biology. Supplements rarely beat food patterns and evidence-based medicine. Anything that promises big cholesterol drops without trade-offs usually sells more hope than reality.

Also, don’t treat cholesterol as a moral scoreboard. High LDL can reflect genetics, age, hormones, and other factors that have nothing to do with willpower. You can still choose actions that help. You just don’t need to turn breakfast into a courtroom.

Think of LDL like rubbish collection. Make less waste by cutting saturated fats and ultra-processed food.

Sort it better with soluble fibre and more whole plant foods. Keep things moving through regular activity and sensible weight control. Bring in medication when the system can’t cope, especially at higher risk.

And yes, food can still be enjoyable.

A cholesterol-friendly meal can be roasted vegetables with olive oil, salmon or beans, a big pile of greens, and a dessert that doesn’t arrive in a foil wrapper. It can be a curry with lentils, brown rice, and yoghurt on top. It can be pasta with tomatoes, olive oil, and a modest sprinkle of cheese rather than a snowfall.

Cholesterol management works best when it stops feeling like a short-term punishment and starts feeling like a long-term upgrade.

Because the weird thing about bad cholesterol is this: it isn’t evil. It’s just doing its job with too much enthusiasm. The goal isn’t to destroy it. The goal is to bring it back to reasonable levels so your arteries can go back to being smooth, boring pipes that never feature in dramatic family conversations.

Somewhere out there, LDL is still ferrying cholesterol to your cells. It can keep doing that. You just want fewer of those ferries, less traffic, and no pile-ups. That’s not a glamorous dream, but it’s a very practical one.