Absinthe Conspiracy: The Green Fairy Myth

There’s something rather irresistible about a drink that promises to drive you stark raving mad whilst simultaneously unlocking your creative genius. For over a century, absinthe has carried this scandalous reputation like a badge of honour, wrapped in emerald mystery and shrouded in tales of hallucinating poets and ear-severing painters. And yet, here’s the thing: the entire story was brilliant marketing bollocks from start to finish.

To begin with, the drink itself began innocently enough. Picture late 18th-century Switzerland, where a French doctor named Pierre Ordinaire lived in exile near the village of Couvet, where he probably brewed herbal remedies and minded his own business. There, he mixed wormwood with anise, fennel, and various other herbs, creating a potent medicinal elixir. Whether he actually invented it, however, or simply nicked the recipe from the Henriod sisters who had been making it all along remains deliciously unclear. Even at this early stage, history was already taking creative liberties with absinthe’s origin story.

From there, what started as medicine quickly transformed into something far more profitable. By 1797, a businessman named Henri-Louis Pernod had seized upon the recipe and opened the first commercial absinthe distillery in Pontarlier, France. As a result, the good doctor’s hangover cure suddenly churned out at an industrial scale. The emerald liquid, with its distinctive anise flavour and eye-watering alcohol content of up to 74 per cent, was about to become France’s drink of choice.

Still, absinthe might have remained just another strong spirit if not for a series of fortunate disasters. In particular, during the 1830s, French soldiers fighting in Algeria received absinthe rations, ostensibly to disinfect dodgy water and prevent malaria. In practice, the troops more likely appreciated getting absolutely smashed in the desert heat. When they eventually returned home, they brought their newfound taste with them, thereby creating France’s first generation of absinthe enthusiasts.

Then came the aphid that changed everything. During the 1860s and 1870s, a microscopic pest called grape phylloxera hopped across from America and proceeded to decimate two-thirds of Europe’s vineyards. Consequently, the Great French Wine Blight sent wine prices soaring. Meanwhile, absinthe manufacturers, who had previously relied on wine alcohol and cleverly switched to cheaper grain and beet alcohol. Suddenly, absinthe was more affordable than wine. For the working classes, this was excellent news. For the wine industry, however, it was nothing short of an existential crisis.

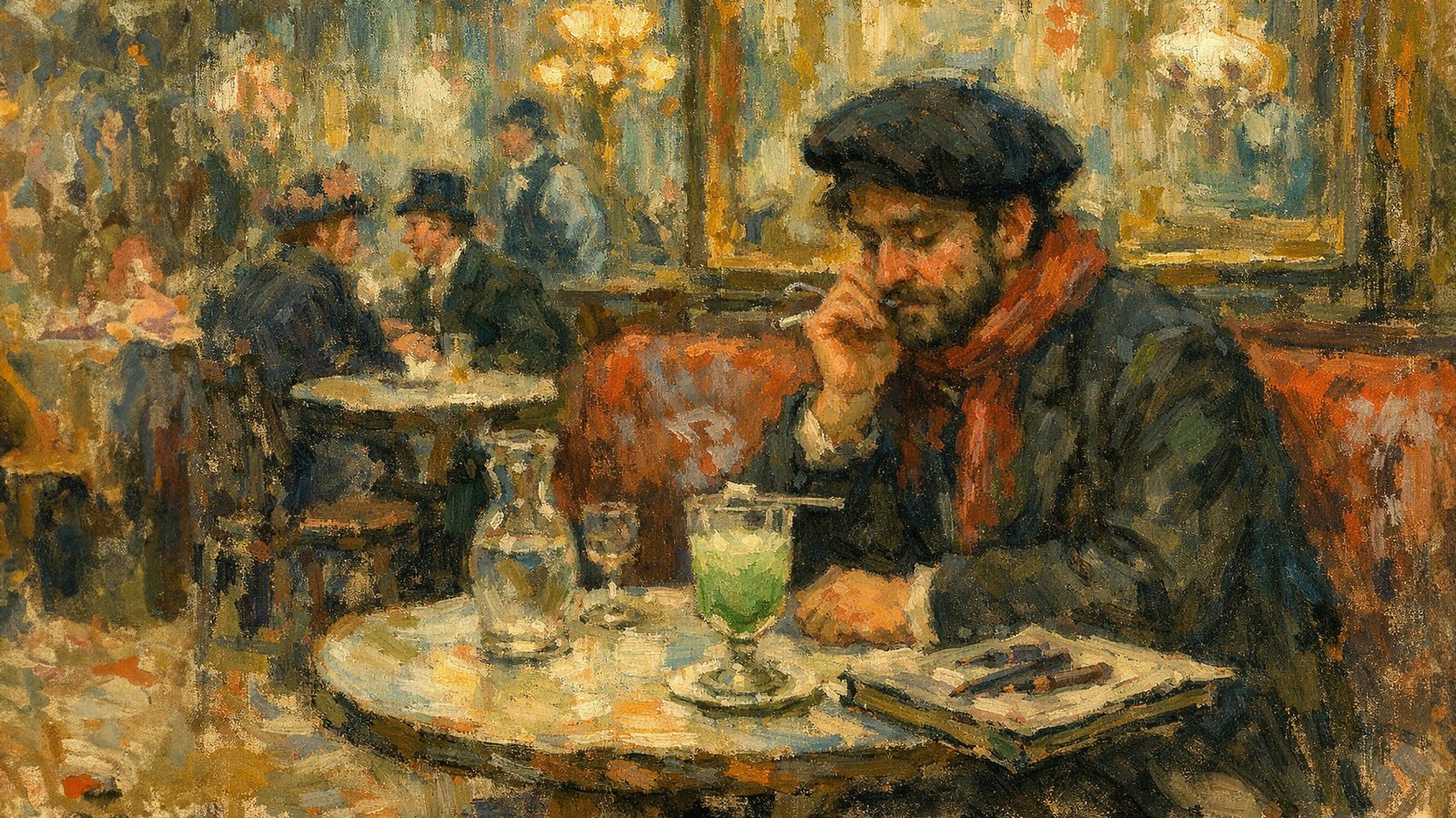

By the 1880s, France was drowning in the stuff. The country consumed 36 million litres annually, whilst at the same time wine consumption hovered around nearly five billion litres. Every evening, between five and six o’clock, Parisian cafés filled with patrons enjoying l’heure verte, the green hour. Rich and poor alike developed elaborate rituals around its preparation, slowly dripping ice-cold water over sugar cubes balanced on ornate perforated spoons. As they did so, they watched the clear spirit transform into a cloudy, opalescent masterpiece. This magical colour change, known as the louche, became central to absinthe’s mystique.

Unsurprisingly, artists and writers absolutely adored the stuff. Vincent van Gogh painted whilst under its influence. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec carried a hollow walking stick filled with it. Oscar Wilde, meanwhile, waxed poetic about phantom tulips brushing his legs after a heavy session. Likewise, Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, Edgar Degas, Paul Verlaine, and Arthur Rimbaud all joined the roll call. Over time, they dubbed it la fée verte, the Green Fairy, and increasingly credited it with unlocking artistic inspiration and heightened perception.

This, however, is precisely where the mythology began to spiral. The artists embraced absinthe partly because of its supposed mind-altering properties, but more prosaically because it was cheap as chips. At the same time, the drink’s distinctive green colour and bohemian associations made it easy to romanticise. Before long, absinthe wasn’t just a drink; it was a symbol of artistic rebellion, creative freedom, and deliciously dangerous decadence.

Meanwhile, the scientific establishment had other ideas. Enter Dr Valentin Magnan, a French psychiatrist with a pronounced axe to grind against alcohol. In the 1860s, he conducted experiments that would ultimately seal absinthe’s fate. Specifically, Magnan exposed laboratory animals to pure wormwood oil and observed them having seizures. On this basis, he concluded that wormwood, and particularly its chemical component thujone, was a dangerous neurotoxin responsible for hallucinations, madness, and violent behaviour. Crucially, this was rather like testing coffee by injecting cats with pure caffeine. Nevertheless, the damage was done.

As a consequence, a new medical condition called absinthism was coined. It was said to involve addiction, hallucinations, tremors, and seizures, and was presented as something far worse than ordinary alcoholism. According to contemporary doctors, this condition transformed respectable citizens into violent criminals and drove artists towards self-destruction. When Van Gogh sliced off his ear in 1888, absinthe took the blame swiftly, despite the fact that he had consumed large amounts of other alcohol and likely suffered from serious mental health issues.

The final nail in absinthe’s coffin arrived in 1905. Jean Lanfray, a Swiss labourer, murdered his pregnant wife and two daughters in an alcohol-fuelled rage. Predictably, the press had a field day with the so-called absinthe murders. What they neglected to mention, however, was that Lanfray had consumed seven glasses of wine, six glasses of cognac, two crème de menthes, and a coffee laced with brandy, in addition to two glasses of absinthe. Out of this alcoholic tsunami, it was the absinthe that took the blame.

At this point, things become especially revealing. The moral panic around absinthe was never purely about public health concerns. Rather, the French wine industry, still reeling from phylloxera and watching absinthe outsell their product, had lobbied aggressively against the green menace. Wine campaigners framed wine as wholesome, patriotic, and agricultural. Absinthe, by contrast, was foreign, bohemian, and socially unsettling. Conveniently, the temperance movement provided cover, while wine producers pulled strings behind the scenes.

As a result, Switzerland banned absinthe in 1910. The United States followed in 1912. France, after holding out, finally capitulated in 1915 under wartime pressure and relentless lobbying. Across Europe, the Green Fairy was exiled, replaced by pastis and other wormwood-free substitutes.

For nearly a century thereafter, absinthe lingered in the shadows. Some families continued distilling it illegally in Switzerland. Spain and Britain, which had never banned it, maintained small-scale production. Ironically, the drink’s legendary status only grew during its absence, fuelled by whispered tales of hallucinations and creative genius.

Eventually, science caught up. From the 1970s onwards, researchers began properly analysing thujone. By the early 2000s, studies of pre-ban bottles revealed something striking: historical absinthe contained very little thujone at all. Average levels hovered around 25.4 milligrams per litre, well below modern safety limits. In fact, some bottles contained none whatsoever. Claims of extreme concentrations turned out to be complete fabrications. Put simply, you would die of alcohol poisoning long before thujone could do anything interesting.

Consequently, modern neuroscience has confirmed what absinthe lovers always suspected. The drink’s effects were never anything more than ordinary intoxication. Hallucinations, madness, and creative breakthroughs can all be explained by excessive alcohol, malnutrition, other substances, and untreated mental illness. In this light, thujone emerges not as a villain, but as a convenient scapegoat.

Eventually, the legal landscape shifted. The European Union lifted restrictions in 1988, and France formally ended its ban in 2011. Today, absinthe is legal across most of the world, subject to thujone limits that are largely irrelevant given how little the spirit contains.

Even so, the mythology refuses to die. Modern producers still flirt with the hallucinogenic legend, fully aware that it sells. The infamous fire ritual, invented in 1990s Prague for tourists drinking sub-par Czech absinthe, continues to circulate online. Traditionalists, meanwhile, regard it as sacrilege.

Ultimately, the real magic of absinthe was never chemical. Instead, it was cultural and social. The preparation ritual slowed drinkers down, forcing them to watch transformation unfold. In doing so, it created space for conversation and reflection. In Parisian cafés during the green hour, people gathered to argue, create, and dream. The drink itself was merely the excuse.

What absinthe truly represented, then, was freedom. Freedom from convention, from respectability, and from the rigid pressures of industrial society. Even its prohibition only strengthened its allure.

In the end, the wine industry’s campaign worked perfectly. Absinthe the campaign eliminated absinthe as a commercial threat while casting it as a moral danger. The fact that we still believe the myth today proves just how effective that campaign was.

So the next time someone tells you absinthe makes you see green fairies, you can smile knowingly. The only fairy involved was the one that convinced generations of drinkers they were experiencing something more than drunkenness. That wasn’t chemistry. That was storytelling.